U.S. International Leadership Still Needed after Climate Bill

The Inflation Reduction Act has proven that the United States has the potential to lead on climate. But further actions are needed if the country is to deliver the global transformations necessary to tackle the climate crisis.

A women's cooperative member cleans a solar panel array that operates the borehole that supplies water to a market garden in the Fulani village of Hore Mondji, Mauritania.

The Inflation Reduction Act has proven that the United States has the potential to lead on climate. But further actions are needed if the country is to deliver the global transformations necessary to tackle the climate crisis.

The Inflation Reduction Act—signed into law by President Joe Biden—delivers the strongest climate action in U.S. history. It finally begins to position the United States to put its domestic house in order and meet its global obligations to tackle the climate crisis. This bold legislation must be only the beginning of additional U.S. actions to mobilize the global progress needed in this decisive decade

The new law delivers $369 billion in additional public investments for clean energy and climate in the United States. These investments will further lower the cost of clean energy technologies, including wind and solar, as well as electric vehicles, heat pumps, and other energy-efficient products. This will speed their adoption across the country, which will have the potential to cut U.S. greenhouse gas (GHG) pollution by 40 percent by 2030 (from 2005 peak levels).

To tackle the climate crisis, the United States needs to move on three fronts simultaneously. First, the United States needs to get its own domestic house in order by rapidly cutting emissions. The Inflation Reduction Act with additional actions by the Biden administration could deliver on this promise. The second part of the strategy must be supporting other countries in rapidly cutting their own emissions. Providing financial and other support is essential to delivering this objective. And finally, the United States must support the poorest communities and countries in adapting to the impacts of climate change and addressing the losses and damages that they are already experiencing. The United States is the world’s largest historical contributor to climate change by a wide margin; it therefore has an outsize responsibility to support countries that didn’t cause the climate crisis but are facing the brunt of the impacts. Further actions will be needed on these three fronts to ensure the United States delivers the global transformations necessary to tackle the climate crisis.

Deliver robust international climate finance

The grand bargain underpinning the Paris Agreement was that every country would be committed to more ambitious climate action, but richer countries would provide support to enable poorer countries to shift to clean energy and adapt to the impacts of a warming world. So far, U.S. overseas climate investment has not lived up to that promise. The United States needs to significantly step up its international climate finance if it wants to effectively deliver on global climate ambitions.

In 2009, developed countries committed to delivering $100 billion a year by 2020 in climate finance for developing countries. But developed countries failed to deliver this goal, reaching only $83 billion in 2020. The United States lags far behind other developed nations in upholding its end of this financing bargain. The European Union (E.U.) and its member states currently provide more than four times as much climate finance (approximately $25 billion in 2020) as the United States, even with a smaller economy.

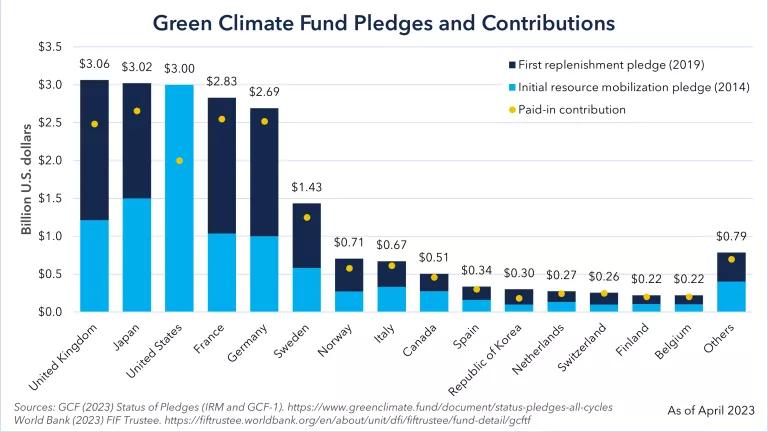

In September 2021, President Biden pledged to provide more than $11 billion a year in climate finance by 2024, a quadrupling of Obama-era levels. Meeting this goal would put the United States on a better path toward being a credible global actor on climate change. To achieve that objective, Congress needs to increase the amount of funding it appropriates to climate-specific international programs. This includes resuming contributions to the Green Climate Fund, where the United States has still only delivered a third of its $3 billion pledge made in 2014. Such funding delivers multiple benefits: It boosts markets for U.S. clean tech exports, enhances national security against disruption from climate impacts, increases U.S. international credibility and influence, and mobilizes the actions outside of the country that are necessary to tackle the climate crisis globally.

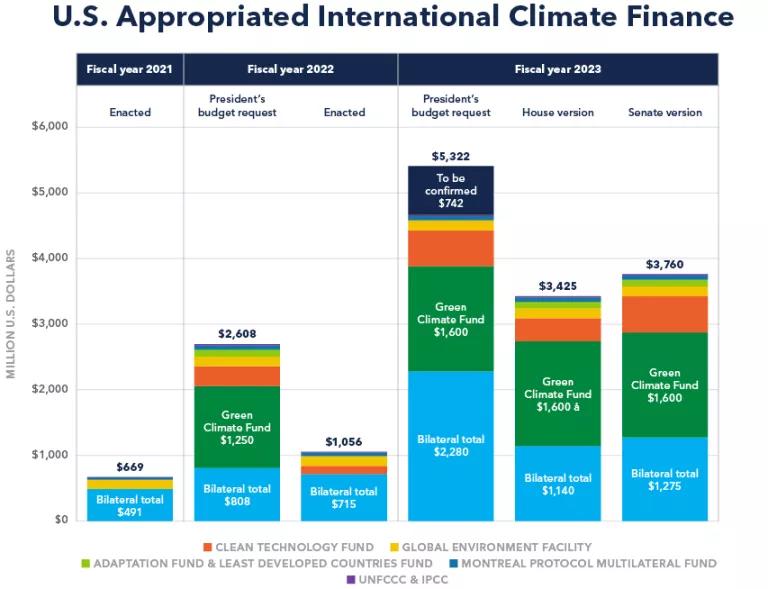

For fiscal year 2022, Congress only approved $1 billion for direct international climate accounts (see chart below). While this amount established the floor, not the ceiling—the total investment may be larger, as the Biden administration has some discretion to spend more— current U.S. climate finance will still fall woefully short of what is needed. President Biden’s $11 billion climate finance budget proposal for fiscal year 2023 would finally begin to meet the moment. The fiscal year 2023 funding bill is currently working its way through Congress, and it is imperative that legislators fight for ambitious levels of climate funding in the final appropriations act.

In addition to Congress approving funding for climate-specific accounts, the Biden administration has other avenues it can pursue to increase international climate finance. The president’s budget request plans for around half of the $11 billion in climate finance to come through U.S. overseas development agencies like the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC), the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), the U.S. Trade and Development Agency (USTDA), and the Export-Import Bank (EX-IM). Biden can direct these agencies to increase their climate work within their general operations. The administration should also scour budgets for unspent and flexible funding that can be directed to international climate action.

Drive an international clean energy first agenda

The Biden administration has a policy in place to eliminate U.S. government support for overseas gas, oil, and coal projects. From 2017 to 2019, the United States provided $2.5 billion per year in direct support for overseas gas projects and an associated amount as a shareholder of the multilateral development banks (MDBs) that provided around $3.4 billion per year of support. By ending these investments, the United States can redirect them to marshal the global renewable energy, energy efficiency, storage, transmission, electric vehicle, and other clean investments that are consistent with our climate objectives. To deliver on this objective, the Biden administration needs to:

- Stop building new LNG export facilities: U.S. LNG exports are at an all-time high. In March 2022, the administration promised an additional 15 billion cubic meters (bcm) of LNG this year to support the E.U. in weaning itself from Russian gas. The United States exported almost 39 bcm of LNG to Europe in the first six months alone, compared to 34 bcm in 2021, and worked with other allies to further redirect supply to European countries. There is no justification for additional LNG supplies or infrastructure expansion in the United States beyond the current pipeline of three additional LNG capacity expansion projects. As we noted in a recent report, “expansion of U.S. LNG infrastructure is unsustainable and deeply harmful for energy security, the climate, people, and communities.”

- Reject oil and gas financing at the MDBs and bilateral finance. The U.S. government committed to eliminating overseas financing of overseas oil and gas projects using a set of detailed criteria, yet its application appears to be uneven across various agencies. In addition, the United States has issued guidance that it will vote down oil and gas projects through the MDBs, except in very rare circumstances.

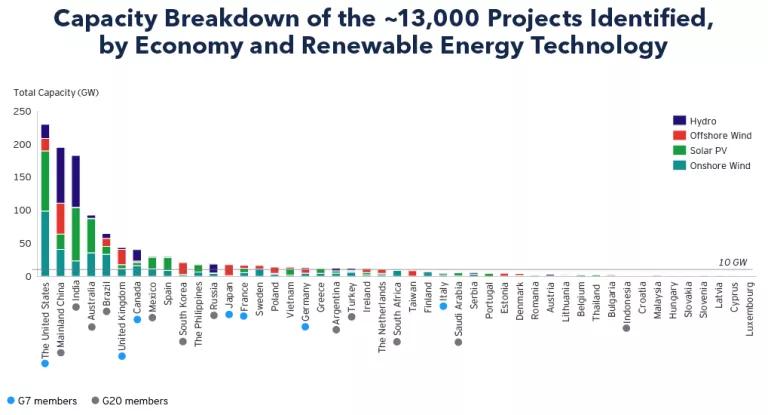

At the same time, the United States needs to increase support for developing countries to rapidly deploy wind, solar, and geothermal power, along with energy efficiency and electric vehicles to help reduce the need for fossil fuels to power their economies. Working with other partner governments, financial institutions, and energy firms, the United States needs to leverage higher volumes of investment for clean technology build-out in developing countries. For example, this effort could help accelerate the global deployment of wind and solar to more than 1,000 gigawatts (GW) annually by 2030, as outlined in the International Energy Agency (IEA) net-zero plans, through all available political and diplomatic channels. The project pipeline is healthy, and the United States has numerous tools to catalyze the needed support. One recent study found there are 13,000 “shovel-ready” renewable energy projects in 40 countries (see figure).

The DFC, Ex-Im, USTDA, U.S. Department of Commerce, and the State Department have significant tools to help U.S. companies and key countries accelerate the deployment of climate-smart technologies. For example, DFC invested in India to support an American company’s solar manufacturing in-country to help India meet its ambitious renewable energy deployment goals. USTDA provides resources to turn a renewable energy deployment idea into a bankable plan of action, such as a feasibility study in the Philippines or solar-plus-storage projects in Nigeria. The Commerce Department has a network of trade professionals located throughout the United States and in embassies and consulates in more than 80 countries that can support American companies with potential clean technology projects overseas.

The Inflation Reduction Act opened the door for a new U.S. national green bank that will help catalyze private investment in clean energy. Similarly, the United States should support other countries seeking to establish their own green banks or specialized facilities that can help build project pipelines, structure transactions, and provide innovative financial instruments and risk-sharing mechanisms to mobilize additional domestic and international private capital to spur the growth of new green markets in developing countries.

Refresh the MDBs for climate action

Multilateral development banks (MDBs)—such as the World Bank, Asian Development Bank, and Inter-American Development Bank—are major climate finance providers. But they could be doing much more. Most MDBs failed to meet their self-designed 2020 climate finance targets; their funding for adaptation remains far too low, and they have struggled to mobilize private finance at the scale required.

The United States is a major shareholder in these financial institutions, so it can have significant influence over their operations. The Biden administration should instruct its board members to push MDBs to scale up their climate financing, especially for adaptation; help speed up the deployment of renewable energy; align their overall operations to support the Paris Agreement and Sustainable Development Goals; and use improved approaches to promote private investment in climate action.

There are tens of billions of new dollars that could flow from making the MDBs work harder and smarter on climate finance.

Deliver support for the most vulnerable around the world to cope with climate impacts

Increasingly severe climate impacts are already being felt around the world. Developing countries have done the least to contribute to the climate crisis but are hit first and worst by the impacts. The United Nations Environment Programme estimates that adaptation costs in developing countries will reach $155 to $330 billion per year by 2030. As the wealthiest country and largest cumulative greenhouse gas emitter, the United States has an outsize responsibility to support the most vulnerable communities in addressing the effects of climate change.

Provision of international funding is an important means to enable developing countries to increase their climate resilience, but mitigation currently receives the lion’s share of climate funding. The Paris Agreement includes a goal that countries achieve a balance in their provision of climate finance between mitigation and adaptation. While some countries have already reached 50:50, only about 25 percent of U.S. climate finance currently goes to adaptation. At COP26, developed countries agreed to collectively double their adaptation finance from 2019 levels by 2025.

Last year, President Biden launched PREPARE, the President’s Emergency Plan for Adaptation and Resilience. It commits $3 billion per year in international adaptation finance by 2024, a sixfold increase on Obama-era spending, and sets out a number of measures to transform the way U.S. overseas development agencies support adaptation. To hit these funding goals, Congress will need to appropriate significantly increased adaptation-specific funding.

Despite these efforts, many communities are reaching the limits of adaptation and are facing unavoidable and irreversible losses and damages. Existing finance for adaptation and humanitarian assistance are not a sufficient response to this reality. The United States needs to ramp up efforts to meaningfully avert, minimize, and address the losses and damages experienced by vulnerable countries and communities.

Implement domestic policies and deliver additional actions under existing laws

The passage of the Inflation Reduction Act has the potential to cut emissions by 40 percent by 2030 (from 2005 peak levels), but the Biden administration has two big tasks to deliver its target to cut emissions 50 to 52 percent by 2030. The Biden administration needs to fully implement the law to realize that 40 percent cut, and it needs to implement additional federal actions by issuing a comprehensive set of standards in at least five key areas.

By delivering on its 50 to 52 percent target, the United States can encourage other high-emitting countries to significantly scale up their actions this decade to help close the emissions gap. This can also have the dual benefit of helping to spur even faster action in the global marketplace. Smart implementation of these investments and standards will help to rapidly bring down the cost of these technologies, create innovative solutions for their deployment, and help to shift the entire global market. After all, significant deployment of solar has played a key role in bringing down its installation costs by more than 60 percent over the last decade, and helped to make it cost-competitive with coal and gas power plants. Similar trends are occurring in wind, electric vehicles, and energy storage. With rapid U.S. deployment, combined with the investments of the other large economies, we could reach another tipping point where the scale of global deployment significantly outpaces current expectations. And that type of nonlinear progress is urgently needed as we are currently off track on the scale of deployment that’s needed globally.

United States needs to lead on many fronts

For more than three decades, the United States has been lagging on efforts to tackle the climate crisis. The Inflation Reduction Act along with additional domestic actions by the Biden administration have the opportunity to begin to position U.S. domestic actions more favorably. However, that will need to be combined with real global leadership that increases climate finance, accelerates the shift from fossil fuel energy to renewables, and helps address the climate impacts that the most vulnerable around the world are already suffering.

The Biden administration needs to pursue every possible avenue to help lead the clean energy transformation the world urgently needs.