U.S. Delivers for the Green Climate Fund and the World’s Most Vulnerable

After a six-year hiatus, President Biden announced the United States is resuming its contributions to the Green Climate Fund with a new allocation of $1 billion.

Joe Thwaites, NRDC

At the Major Economies Forum leaders meeting President Biden convened today, he announced the United States is resuming its contributions to the Green Climate Fund (GCF) with a new allocation of $1 billion. Renewed U.S. support to the GCF is vital to on-the-ground progress and sends an important political signal. The GCF is the world’s largest international fund dedicated to helping developing countries fight the climate crisis. This U.S. investment provides a lifeline for communities strapped for resources to invest in clean energy and adaptation to mounting climate impacts. Investing in this innovative fund will spur global climate progress and is strongly in America’s interest.

"As large economies and large emitters, we must step up and support [developing] economies. So today, I’m pleased to announce the United States is going to provide $1 billion to the Green Climate Fund, a fund that is critical in ways to help developing nations that they can’t do now."

President Joe Biden, Remarks at the 2023 Major Economies Forum on Energy and Climate

GCF investments advance U.S. interests

The GCF is a robust investment for the U.S. and helps advance American interests in at least four key areas:

- Bolsters U.S. jobs through creating clean technology export opportunities GCF investments spur global clean energy deployment, creating new markets for American clean technology companies. The GCF works directly through a number of U.S. institutions; the impact investors Acumen Fund and Pegasus Capital Advisors are accredited entities, delivering projects in Africa, Asia and Latin America. The Inflation Reduction Act is poised to catalyze a major expansion of U.S. clean technology innovation and manufacturing. Exporting this technology to other countries can boost the U.S. jobs and the economy while helping other countries to reduce their emissions and build resilience. Out of the top 30 markets for U.S. renewable energy exports, more than half are eligible to receive funding from the GCF.

- Invests in countries vital to U.S. national security interests. The GCF finances projects that boost resilience and build livelihoods in countries of key strategic interest for the U.S., including Egypt, Jordan, Mali, Pakistan, as well as the Indo-Pacific region. The GCF also funds projects in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras in Central America’s Northern Triangle. By promoting resilient economic development, it helps address some of the root causes of instability that can devastate lives and destabilize regions.

- Maintains U.S. influence in the GCF. The U.S. played a key role in the GCF’s establishment, design, and operations. But with its six-year hiatus in contributions, U.S. influence has been put at risk. African governments sought to block the U.S. from co-chairing the GCF’s governing Board this year, citing the U.S. failure to deliver its $3 billion pledge. Australia is a telling example; in the early years they were a major player in the Fund, co-chairing the Board for two years. But then their government stopped contributing to the GCF and soon after lost their Board seat. U.S. contributions help maintain the U.S.’s role in shaping the GCF’s evolution and avoid ceding influence to other countries who may not share its interests.

- Spurs other countries to step up their own investments. During the GCF’s initial capitalization in 2014, the U.S. played a pivotal role in encouraging other countries, such as Japan, Australia, and Canada, to step up and make significant pledges. When the U.S. sat out the first replenishment in 2019, so did Australia. Meanwhile, Japan and Canada did not increase their replenishment pledges from their 2014 levels. While European governments continued to scale-up their contributions to the GCF, filling the gap left by the U.S., they have been clear that resumed U.S. contributions are essential to building political support in their own countries to increase their funding; their citizens want to see the world’s biggest economy and cumulative emitter doing its part. Without U.S. contributions, developing countries have also been under less pressure to contribute. Nine developing countries made pledges in 2014, but only two did in 2019. A key strategic objective of developed countries has been to broaden the base of climate finance contributors. Without the U.S. meeting its commitments, the pressure on wealthier emerging economies such as Gulf states or China, to step up and contribute is significantly diminished.

The GCF provides a powerful bang for the buck

When governments agreed to create the GCF in 2010, the climate finance architecture already included a number of other multilateral climate funds. But there was a clear sense that these other institutions, despite doing useful work, weren’t fully meeting the climate funding needs of developing countries. The GCF was designed to be a game-changing institution, learning from the experiences of other funds and bringing innovation to how climate finance is delivered:

- The largest climate fund. With $20.6 billion in pledges and $17 billion in funding paid in the GCF is by far the largest international fund dedicated to climate action. It has approved $12 billion in funding for 216 projects in 129 developing countries. This funding is projected to reduce 2.5 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent, equivalent to the annual emissions of 669 coal power plants, and to increase the resilience of 912 million people to climate impacts.

- The most contributors. The GCF has received funding pledges from 46 countries, including nine developing countries, giving it the most diverse contributor base of any international climate fund. The fact so many countries have invested in the Fund, including non-traditional donors, is a vote of confidence in its innovative and representative approach. The GCF is also exploring options to receive private sector and philanthropic contributions.

- A mandate to support the Paris Agreement with transformational climate investments. The GCF is explicitly named in the Paris Agreement as a key institution to help developing countries meet their climate commitments, vital to keeping the goal of holding temperature rise to 1.5°C. Where other funds give all eligible countries a small allocation of money, the GCF is mandated to fund the most transformative projects.

- A wide variety of financial instruments to mobilize private finance. While most other climate funds focus only on grants or loans, the GCF can also make equity investments, issue guarantees, and make results-based payments. These diverse financing options help the Fund catalyze other sources of investment, including the private sector. For every dollar the GCF has approved in its own funding, it has mobilized $2.75 from other sources. This means its $12 billion in capital has catalyzed total investments of $45 billion. The Fund was designed to pay particular attention to mobilizing private finance. Its Private Sector Facility brings together major global banks and investors and micro-, small-, and medium-enterprises in developing countries making investments to catalyze and scale markets for clean technology and climate resilience.

- Funding is allocated to a variety of objectives, with dedicated funding for the most vulnerable. The GCF invests in eight key areas: energy; transport; buildings and industries; forests and land use; health, food and water; livelihoods of people and communities; ecosystems; and infrastructure and the build environment. The Fund has a mandate that its funding be split 50:50, in grant-equivalent terms, between emissions reductions and adaptation to climate change. Adaptation has often been underfunded globally, receiving only a quarter of overall climate finance from developed to developing countries, so this mandate helps address the imbalance. Furthermore, of the GCF’s adaptation funding, half is set aside for particularly vulnerable countries, like the least developed countries, small island developing states, and African countries. The GCF’s focus on funding adaptation in the most vulnerable countries is especially important since this is an area where the private sector likely can’t and won’t invest.

- Broad and diverse partnership model. The GCF is set up to work through a much broader array of institutions. While other funds primarily work through multilateral development banks or UN agencies, the GCF works with these but many more, including private sector entities, local NGOs, and government agencies. The GCF has accredited 114 entities, including 72 in developing countries. By investing in institutions in developing countries, the Fund helps build government, private sector, and civil society capacity to raise and deploy resources on their own, rather than being dependent on international agencies.

- Fast operations. During its start-up phase, the GCF often struggled to get funding out the door in a timely manner. This was not entirely the Fund’s fault; many of the bottlenecks in the early years were due to implementing entities, such as the World Bank, which has a generally poor track record in moving funding swiftly, taking a long time to sign the necessary legal paperwork to get funding flowing. Many of these hurdles have now been overcome, and the GCF is approving and disbursing funding much faster. The average time from GCF funding approval to disbursement has fallen from 19 months in 2018 to 13 months in 2021, making it one of the fastest among peers. In fact, the GCF is now operating so efficiently that it is approving funding nearly as fast as donors are paying it in; the biggest constraint now is the availability of resources, another reason why the new contribution from the Biden administration is so important.

- More equitable and inclusive governance. The GCF’s governing Board is made up of 12 developed and 12 developing country representatives. Whereas multilateral development banks allocate votes based on shareholding, giving the richest countries most influence, the GCF operates on a one board member, one vote basis. This gives developing countries more of a say in how funding is spent, allowing the fund to be more responsive to recipient country needs.

- Best-in-class safeguards, accountability, and transparency. Learning from the lessons of other international financial institutions, the GCF was designed to have best-in-class anti-corruption rules, environmental and social safeguards, and gender policies. Three independent units evaluate the GCF’s performance, provide redress for communities where projects take place, and investigate allegations of fraud, corruption, misconduct. The Fund is also far more transparent than peer institutions: Board meetings are webcast and available to watch again and Board decisions and project documentation are all made available on the GCF’s website in a timely manner. The U.S. was instrumental in pushing for these high standards.

These design features mean that of the multitude of climate funds out there, the GCF gets considerable bang for its buck. This is why other members of the G7, and advanced economies in general, have invested significantly in the GCF.

A brief history of the U.S. and the GCF

The Green Climate Fund was created in 2010, with a mission of providing financial support to developing countries to take transformational action to reduce their emissions and build resilience to climate change.

Support for the GCF underpinned the grand bargain at the heart of the Paris Agreement: that all countries need to do much more to tackle the climate crisis, but that the poorest countries, who did the least to cause the problem but are hit first and worst by its impacts, require support from the richest and highest polluting countries. The U.S. is both the largest economy in the world and the largest cumulative greenhouse gas emitter by a wide margin, so has an outsized responsibility to shoulder.

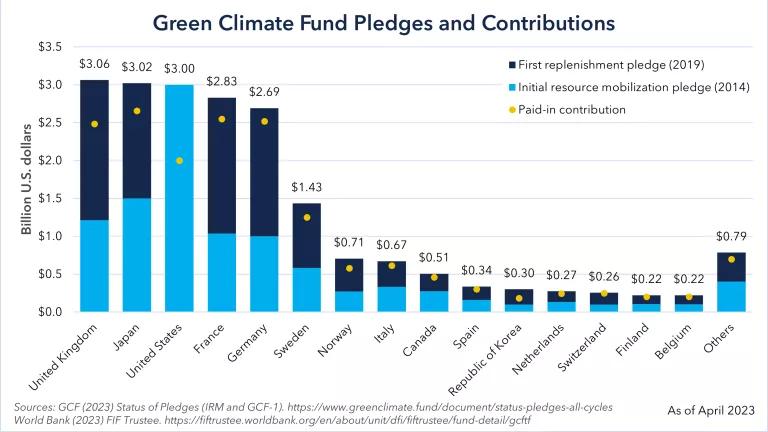

President Obama recognized this imperative, and the U.S. played a key role in designing the GCF and standing it up. In 2014, the U.S. made the biggest pledge to the Fund’s initial capitalization: $3 billion out of $10.3 billion in total pledges from 46 countries. The Obama administration paid in $1 billion of this pledge before leaving office, in two $500 million tranches in 2016 and 2017.

However between January 2017 and this week, the United States stopped contributing to the Fund. President Trump was notoriously hostile towards the GCF, often deriding it on the campaign trail and as President in his speech pulling the U.S. out of the Paris Agreement.

In 2019, other countries came together to replenish the Fund, pledging an additional $10 billion. While other G7 countries like the United Kingdom, Germany and France doubled their 2014 pledges, the U.S. sat on the sidelines. This meant the U.S. went from being the largest pledgor to the GCF in 2014 to, until this week, the sixth largest contributor in terms of paid-in funds. The U.S. sat behind Sweden, a country with a population 1/30th the size and an economy more than 44 times smaller. The failure to deliver its GCF pledge has dented the United States’ standing in the world. Other countries have frequently raised the U.S. non-delivery of its GCF pledge to excuse themselves from doing more to tackle the climate crisis and pointed to the U.S. inability to deliver on its commitments to try to win other countries over to their positions in global climate negotiations. Failure to contribute has come at a real cost to America’s credibility, not just on climate, but also for its broader reputation as a country that upholds its promises.

“The outstanding [GCF] pledge amount negatively impacts U.S. influence and diplomatic standing.”

U.S. Department of the Treasury, Fiscal Year 2024 Congressional Budget Justification

That’s why the U.S. resumption of GCF contributions after a six-year hiatus is such an important and welcome development. In 2021 Biden declared “America is back” on climate, to some healthy global skepticism at the time. The Inflation Reduction Act is now putting the U.S.’s house in order domestically by unlocking massive investments in clean technology, but did not include any international climate investments. After two years of disappointing funding bills for international climate programs, this new $1 billion GCF contribution puts a spring in the U.S. step in terms of meeting its international climate commitments. The $1 billion contribution Biden announced today moves the U.S. up to fifth place in terms of paid-in funds, after Japan, France, Germany, and the UK.

What’s next?

Biden’s contribution means the GCF will have an additional $1 billion on hand to deepen its vital investments. This funding will have major positive impacts, with the money getting put to work straight away. As noted above, there is more demand for GCF funding than capital in its coffers, so the Fund has needed to delay project approvals. With an additional $1 billion from the U.S., the GCF will be able to approve more projects more quickly, getting money to communities in need.

Thanks to the Biden administration—including Secretary Kerry—and climate leaders in Congress, the U.S. is a big step closer to delivering on its climate finance promises. But there is still much more to do. The U.S. pledged $3 billion to the GCF in 2014. This new contribution takes them two-thirds of the way to fulfilling the nine-year-old pledge. The Biden administration must work urgently with Congress to prioritize fulfilling the remaining $1 billion in the fiscal year 2024 appropriations bill.

Furthermore, the GCF will be hosting a pledging conference for its second replenishment in October 2023. Having sat out the 2019 replenishment, it is critical that the U.S. come with an ambitious pledge and a credible pathway to delivering it. The U.S. is co-chairing the GCF Board this year, and other countries are looking to them closely to calibrate the ambition of their own pledges. If America wants to bolster its global climate credibility and encourage new donors to come forward, it must continue to invest in the GCF.