Delivering More Action at Climate Summit in Glasgow

Leaders came to Glasgow with the task of putting the world on a much more plausible pathway to “keep 1.5°C alive”. To do that, they needed to set more ambitious commitments and take noticeable steps to strengthen their actions right now.

COP26 Plenary

Leaders came to the climate summit in Glasgow with a daunting, necessary, and achievable task—put the world on a much more plausible pathway to “keep 1.5°C alive”. To do that they needed to set more ambitious commitments and take noticeable steps to strengthen their actions right now. We needed more pledges and actions to drive down emissions in this “decisive decade”. The climate summit in Glasgow reached the strongest global consensus yet, but much more work lies ahead if we are to stave off the worst impacts of the climate crisis. The atmosphere doesn’t care what you promise to deliver.

Pledges get us closer to 1.5°C (2.7°C)

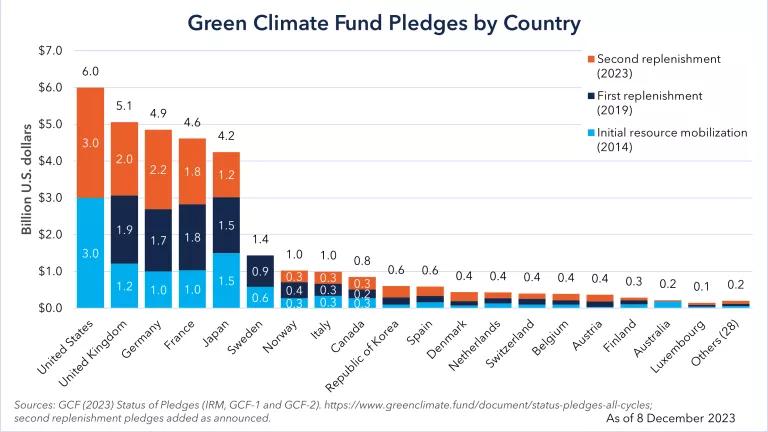

In mid-2010, the pledges from countries and sectors put the world on a trajectory of 2.9°C. This is an improvement from the 4°C pathway we were headed to before countries agreed to the Paris Agreement. Yet, the current pledges coming into COP26 were insufficient to “keep 1.5°C alive” and our current actions, if continued without stronger steps, was likely to make “1.5°C difficult or impossible to reach”. The announced national targets under the Paris agreement prior to Glasgow put the world on a 2.7°C trajectory. And the world’s current actions placed us in an even worse trajectory. If we continued with current policies, the world will likely be heading for a 2.8-2.9°C world. As a result, the climate summit in Glasgow needed to deliver both on pledges and near-term actions.

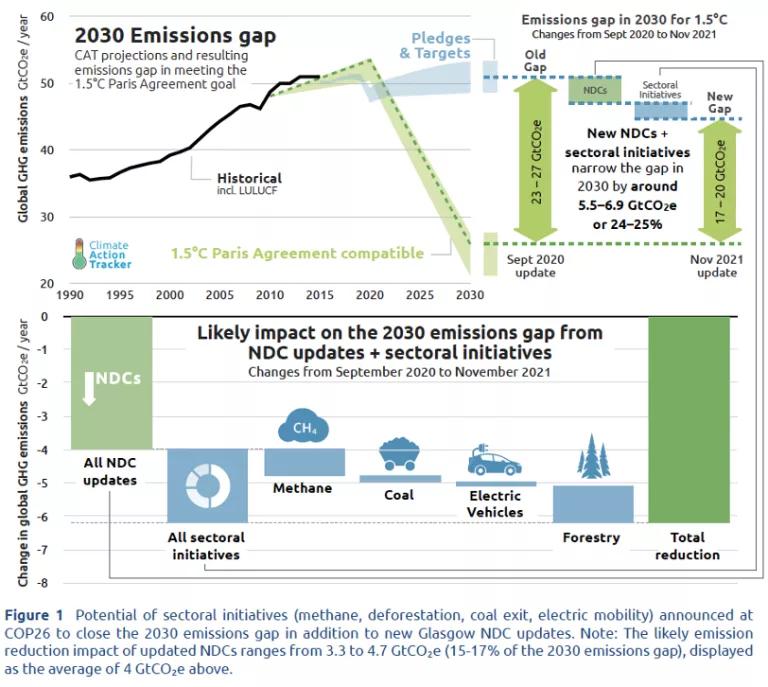

Delivering this “decisive decade”. The national pledges and sectoral commitments made this year bring us closer to a 1.5°C pathway but only if they are delivered. And even if these commitments are delivered, the world still needs to do more to put us on a safer climate trajectory. If the national commitments through 2030 are fully implemented, the world will be headed for a 2.4°C trajectory—with a range of 1.8°C to 3.3°C depending on how those targets are delivered. This would leave us with a 2030 “emissions gap” of 19-23 gigatons of carbon dioxide equivalent (GtCO2e).

However, Glasgow also witnessed important new sectoral commitments around fossil fuels, forests, zero emissions vehicles, and finance. If the countries that agreed to these commitments delivered, these sectoral commitments could further action this decade. These sectoral initiatives would reduce emissions by a further 2.2 GtCO2e—an additional 9 percent reduction. This would leave us with an emissions gap in 2030 of 17-20 GtCO2e (see figure).

If more countries joined these initiatives, an additional 6.15-8.15 GtCO2e of emissions reductions could be delivered in 2030. This would leave the 2030 emissions gap at 8.85-13.85 GtCO2e.

Delivering after 2030. This trend could be further reduced if countries deliver on their long-term net zero targets, with the world headed for a global temperature increase of 1.8°C in 2100 (with temperatures likely peaking at 1.9°C). (Carbon Brief has a good summary of the various analysis).

At the Glasgow climate summit, we’ve seen important new country, sectoral, and financial commitments. Here is a breakdown of the main ones.

New national commitments

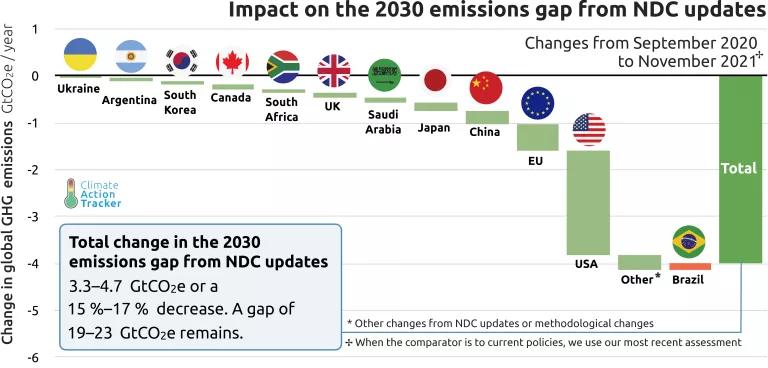

Under the Paris Agreement countries were to adopt stronger 2030 climate targets since we knew leaving Paris that country actions “must be the floor, not the ceiling” of ambition this decade. Over the course of the year, a growing number of countries announced stronger action before 2030 including from the:

- European Union going to 55 percent below 1990 levels by 2030 and announcing legislative proposals to deliver on that commitment (increasing from 40-45% below 1990

- United States going to 50-52 percent below 2005 levels by 2030 (increasing from its 26-28% below 2005 level target in 2025)

- Japan going to 46-50 percent below 2013 levels by 2030; 44-48 percent compared to 2005 levels in 2030 (increasing from 26 percent below 2013 levels by 2030; 23 percent below 2005 levels)

- Canada going to 40-45 percent below 2005 levels by 2030 (increasing from 30 percent below 2005 levels)

- South Africa setting an emissions level in the range of 350–420 MtCO2e for 2030, equivalent to a 3–23% increase above 1990 levels excluding land-use change and forestry (the upper end is now 31% lower and the lower end 12% lower than in the previous target)

- Argentina setting an absolute, economy-wide and unconditional goal of limiting greenhouse gas emissions to 359 MtCO2e in 2030 (a 26 percent increase from their previous target).

At COP26, additional countries announced new targets to further cut emissions this decade:

- South Korea going to 40% below 2018 levels by 2030 (increasing from 24.4% below 2017 levels)

- India increasing its non-fossil energy capacity target to 500 GW by 2030 (making 60 percent of India’s power capacity fossil-free by 2030 which is a significant step-up from its current 40 percent target), meeting 50 per cent of its energy requirements with renewable energy by 2030 (with about a quarter of the energy requirements in electricity sector met through renewable energy today), reducing its total projected carbon emissions by one billion tons from now to 2030, reducing the carbon intensity of its economy by 45 percent compared to 2005 levels in 2030 (strengthening from the current 33-35 percent target). See NRDC reaction.

- South Africa agreeing to rapidly phase-out coal power plants, ramp-up renewable energy, spur electric vehicles, and support green hydrogen with the funders committing to mobilize resources to assist in this effort.

Unfortunately, this year some major countries have announced weaker targets or national actions that will significantly take us backwards—such as Brazil’s weaker national target, Mexico’s movement away from renewable energy which is critical to meet its current national target, Australia’s failure to come forward with stronger action this decade, and Russia’s missing in action 2030 ambition.

In all, these increased national targets are estimated to close the emissions gap by 3.3-4.7 GtCO2e in 2030—leaving a 19-23 GtCO2e gap (see figure).*

Some major countries will have to significantly step-up next year if the world has a shot of keeping 1.5°C alive.

New Sectoral Initiatives

The Glasgow climate summit also witnessed several important new sectoral announcements. If fully implemented these could help deliver even more ambition this decade—delivering a further 2.2 GtCO2e emissions cut in 2030 to close the emissions gap. If more countries joined these initiatives, an additional 6.15-8.15 GtCO2e of emissions reductions could be delivered in 2030 (see figure). This would leave the 2030 emissions gap at 8.85-13.85 GtCO2e**.

Powering past coal. In the run-up to Glasgow and during the conference, several important commitments were delivered that will help countries shift away from coal and towards renewable energy. To be on track for a 1.5°C trajectory, coal-fired power plant emissions need to decline rapidly. In Glasgow, over 45 countries and over 30 companies and regions have committed to a series of actions to shift from coal to clean by achieving a transition away from unabated coal power generation in the 2030’s for major economies and in the 2040’s globally. This includes Botswana, Canada, Chile, Denmark, Egypt, European Union, France, Germany, Hungary, Indonesia, Italy, Kazakhstan, the Netherlands, Poland, Senegal, South Korea, Ukraine, United Kingdom, Vietnam, and Zambia. Seven new subnational governments, three new energy companies and 11 new financial institutions have committed to end unabated coal power by joining the Powering Past Coal Alliance. This alliance now has nearly two-thirds of the OECD and European Union governments as members committed to phase out coal by 2030. This joins the recent commitments from South Korea, Japan, China, and the entire Group of 20 countries who committed to end all public financing of overseas coal plants this year.

Emerging efforts to retire coal fleets early. We’ve also seen emerging efforts to help countries with large existing coal fleets retire these plants early. It is critical to help countries implement a managed and just transition of the existing coal power plant fleet since running these plants through their useful life will result in too much emissions to keep 1.5°C alive. Four funders committed to help speed up the transition from coal to clean energy in South Africa by committing to mobilize $8.5 billion over the next three to five years. The Asian Development Bank is beginning to develop an effort to mobilize public and private investments to help key Southeast Asian countries with this transition (Indonesia and the Philippines are the initial partners) and private funders have begun to provide technical assistance to help develop more concrete proposals.

Moving beyond oil and gas. Attention is now increasing on the need to phase-out oil and gas production if the world is to move on a 1.5°C trajectory. Governments are planning to produce 57 percent more oil and 71 percent more gas than is consistent with 1.5°C trajectory so it is essential that countries rapidly shift their production plans while simultaneously driving down the consumption of fossil fuels. Almost 35 countries and five financial institutions signed onto a statement on international public support for fossil fuels that commits them to “end new direct public support for the international unabated fossil fuel energy sector by the end of 2022, except in limited and clearly defined circumstances…” (See NRDC reaction). Led by the European Investment Bank and the United Kingdom it includes: U.S., the Netherlands, Italy, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Spain, Agence Française de Développement (AFD), East African Development Bank (EADB), and Financierings-Maatschappij voor Ontwikkelingslanden N.V. (FMO). A recent report estimated that around $16 billion per year of public financing has been going to overseas gas development—nearly four times as much as for renewable energy—with public support for overseas oil at around $7 billion per year. So, shifting public finance will be a key part of this puzzle going forward. And a new coalition has been launched—the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance (BOGA)—to facilitate the managed phaseout of oil and gas production. It launched with eleven national and subnational governments joining as initial leaders (see NRDC reaction).

Mobilizing more renewable energy. As countries shift away from coal and gas for their electricity, it is critical that they are provided with the tools to tap into the growing renewable energy and energy efficiency opportunity. There are more than 13,000 “shovel-ready” renewable energy projects in 40 countries that are ready to be financed right now (as we discussed in our side-event). At Glasgow, several new announcements will help countries tap into this existing renewable energy pipeline and develop the next tranche of projects. India and the United Kingdom launched an effort to help countries build the necessary electricity grid to tap into their massive solar energy potential. The United States became the 101st country to join the International Solar Alliance to help countries around the world tap-into the solar electricity potential. A new partnership—Global Energy Alliance for People & Planet—was launched with an initial $10 billion of funding from philanthropies and development banks to support energy access and the clean energy transition. The U.S. launched the Net-Zero World Initiative to help mobilize technical assistance and finance to drive energy system decarbonization in participating countries.

Spurring energy efficiency. To meet the world’s growing energy needs and help enable the shift towards renewable energy, it is essential that key countries and sectors better deploy the massive untapped energy efficiency potential. Twelve major countries signed onto the Product Efficiency Call to Action with the goal of doubling by 2030 the efficiency of four key products (refrigerators, air conditioners, motors, and lighting) that account for 40 percent of global energy consumption. So far, the governments of Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Denmark, Germany, Ghana, India, Japan, South Korea, Nigeria, Sweden, and the United Kingdom have signed onto the commitment.

Reducing the super-pollutant methane. Over 100 countries representing nearly half of human-caused methane emissions have now signed onto a pledge to reduce global methane emissions by at least 30% from 2020 levels by 2030. More than $328 million in funding support from global philanthropies has been committed to support this effort. Delivering on this pledge would reduce warming by at least 0.2°C by 2050. As a step towards this, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency proposed the first national U.S. limits on methane emissions from existing oil and gas operations and stronger requirements for new wells and equipment, Canada committed to cut oil and gas methane 75 percent by 2030, and China announced it will bring forward a methane action plan next year (see NRDC reaction).

Tackling forest loss. In Glasgow, several commitments were announced to help protect, conserve and restore the world’s forests. Over 140 countries committed to: “halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030”. This includes commitment to this goal from: Brazil, Bolivia, Canada, China, Colombia, Costa Rica, Democratic Republic of the Congo, European Union, Ecuador, Madagascar, Norway, Panama, Peru, Russia, United Kingdom, U.S., and Vietnam. To assist in delivering on this goal, 12 donor countries pledged to provide $12 billion of public climate finance from 2021 to 2025 including an explicit finance commitment to help the carbon rich Congo Basin in Africa. In recognition of the critical role of indigenous peoples and local communities, major donors pledged $1.7 billion from 2021-2025 to help these players with tenure rights to support their role as guardians of forests. The U.S. released a whole-of-government strategy to conserve global forests including a plan to dedicate up to $9 billion of international climate finance through 2030 to this effort. We are also seeing emerging signs that major financial institutions will stop supporting deforestation with 33 financial institutions with over $8.7 trillion of global assets committing to phase out deforestation driven agricultural commodities in their portfolios by 2025. And there is an emerging push to address deforestation and degradation in the supply-chain with new commitments from major countries to tackle the trade in key commodities that threaten forests. These declarations all require a reckoning in northern forests where deforestation and degradation is occurring too rapidly and a halt of biomass for electricity generation as these important pieces were missing.

Shifting to electric vehicles. To be on path for 1.5°C it is essential that we decline transportation emissions rapidly. As a result, it is imperative that we rapidly shift to electric vehicles with a global drive to have 100 percent electric sales for buses and two/three-wheelers by 2030, passenger vehicles by 2035, and freight trucks by 2040. As a step towards that goal, 31 national jurisdictions, 6 major automakers, and numerous subnational governments and companies announced commitments to reach a 100 percent zero-emission vehicle sales goals for passenger vehicles in leading markets by 2035 and globally by 2040 (See NRDC reaction). This includes the United Kingdom, Canada, India, Poland, Washington State, California, Ford, GM, Volkswagen, Mercedes-Benz, BYD, Jaguar Land Rover, and numerous corporations with large fleets.

From Promises to Action

As we leave the Glasgow climate summit, we have more hope for keeping “1.5°C alive” this decade. But we also leave with a compelling sense of urgency as our current actions have yet to rise to the challenge of the climate crisis. That means major countries will need increase their ambition even more this decade as there is a large emissions gap. It means more countries, companies, financial institutions, states/provinces, and cities committing to help drive key sectoral transformations. And most importantly it means rapidly turning our pledges, commitments, and goals into concrete action.

We leave Glasgow with more promise, but we now must roll-up our sleeves and deliver more action. Because only with that effort will we protect people and the planet from the worst impacts of the climate crisis.

* This didn’t include India’s enhanced 2030 actions as Climate Action Tracker didn’t assess the implications of this compared to its NDC as there is a bit of uncertainty on the exact definitions in the India announcement. And this didn’t include South Africa’s announcement as it wasn’t clear how this would manifest in South Africa’s revised NDC.

** These reductions are additional to the "gap closing" cuts from Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) for these measures. For example, cutting methane emissions is a part of a number of countries pathways to their 2030 targets so these cuts are what go beyond their current 2030 NDCs.