When Customers and Investors Demand Corporate Sustainability

Through shareholder resolutions, letters, and activism, consumers and shareholders can push companies to clean up supply chains—and their reputations.

A protest outside of P&G headquarters during a 2019 shareholder meeting in Cincinnati calls attention to the company’s cutting down of the Canadian boreal forest to make its paper products.

NRDC

For decades, we’ve been flushing one of earth’s most important ecosystems down the toilet. As the world’s largest intact forest, the Canadian boreal is a hotbed of biodiversity and the keeper of 208 billion tons of carbon within its soils, peatlands, and trees. And yet, for decades, companies like Procter & Gamble (P&G) and Kimberly-Clark have contributed to the clearcutting of more than a million acres of this forest each year to make tissue products like toilet paper.

The brands of these top U.S. tissue manufacturers have received Fs on NRDC’s annual sustainability scorecard for products such as toilet paper, facial tissue, and paper towels since the group began its ratings in 2019. But this year, Kimberly-Clark has been making moves to get to the head of the class, potentially joining the ranks of other companies that make their products with recycled materials or alternative fibers (like bamboo) instead of natural forest fiber.

Kimberly-Clark—the owner of household brands like Kleenex, Cottonelle, and Scott—detailed its new commitment to becoming more sustainable in a Forest, Land, and Agriculture Policy published earlier this month. The company aims to go “natural forest–free,” meaning it would no longer source fiber from the most ecologically important areas of the boreal and other forests. Kimberly-Clark says it would also avoid forest degradation (such as the negative impacts that industrial activities like clearcutting can have on a forest’s biodiversity, carbon storage, and overall ecological integrity) in its supply chain. According to the company, it has already reduced the amount of natural forest fiber it uses by 39 percent (compared to 2011 levels), and it would like to get that figure to more than 50 percent by 2030. Though Kimberly-Clark has not given itself a hard deadline to become completely natural forest–free, it hopes to do so at some point “beyond 2030.”

“This is a big deal because it indicates that the company sees a future where tissue products don’t need to be made at the expense of climate-critical forests,” says Shelley Vinyard, a corporate campaign director for NRDC who works on northern forests. Ideally, the move could lead its competitors, like P&G and other companies in the personal care industry, to adopt similar policies concerning the sources of their paper products.

Stacked logs at a lumber mill in Radium, British Columbia, Canada

James Gabbert/Getty

So what prompted Kimberly-Clark to turn over this new leaf?

“I see it as a direct result of the work NRDC has done over the last five years to draw attention to the fact that companies like Kimberly-Clark are fueling the degradation of the boreal,” says Vinyard.

But you don’t need to be a big environmental group to call out a corporation’s destructive business practices. Consumers and investors can also be pivotal in getting companies to clean up their acts.

In recent years, a number of corporations have made commitments to reduce their environmental footprints—moves that often come after years of demands from nonprofits, consumers, and activist investors to change company policies and supply chains. Levi’s, for example, stopped using PFAS in its clothing manufacturing. Pressure from the environmental nonprofit Greenpeace pushed the company to adopt a detox commitment, which resulted in the company phasing out these “forever chemicals” in its supply chain.

Groups like the Rainforest Action Network and Greenpeace asked the multinational food company Kraft Heinz to disclose its sources of palm oil, the growing of which can often clear huge swaths of tropical forest and threaten species, such as orangutans, with extinction. News outlets published articles on the health effects of working on palm oil plantations, and shareholders proposed that the company commit to eliminating deforestation practices. Eventually, the company responded with a new policy outlining how it would better respect forests and nature in its ingredient sourcing.

ADM (Archer-Daniels-Midland Company), one of the world’s largest soy and corn growers, found itself in a similarly defensive position after it was linked to the destruction of thousands of acres of Brazilian Cerrado in 2018 in order to convert it to farmland. Facing pressure from shareholders, the company published a report that led to a policy in which ADM pledged to require its direct suppliers to stop converting wild land to cropland by 2025, and its indirect suppliers to do the same by 2027.

A pileated woodpecker; a bull elk

Artur Widak/NurPhoto via AP

; 2)K.D. Kirchmeier/Getty Images

Customer feedback

“We need consumers engaged in demanding sustainable products,” says Ashley Jordan, a boreal advocate for NRDC. “Companies say, ‘We're providing what people want.’ But people can make it clear that we also want options that allow for a livable future.”

Consumers and investors can spur corporations to act by writing letters, having meetings, sharing information, filing shareholder proposals, and making investment decisions with activism in mind.

“Something that I think people don't realize is that companies are made up of people, and the direction that the company goes depends ultimately on decisions made by individuals,” says Andrew Shalit, a shareholder advocate at Green Century Capital Management, a sustainable investment firm.

And in recent years, companies at least appear to be more open to following environmental, social, and governance (ESG) principles. A 2021 survey showed that 88 percent of publicly traded companies have ESG initiatives, and according to a report by PwC (PricewaterhouseCoopers), companies appear to be elevating sustainability officers to more influential positions. Still, promoting a sustainability officer doesn’t mean much unless the company makes actual progress in that area. That’s where consumers and shareholders can step in to help keep companies honest.

People interested in asking a company to make a change shouldn’t be afraid to reach out to these sustainability officers, or to other company officials, to start a conversation, Shalit says. “An investor can send a letter to a Fortune 500 company, and soon after, they can be sitting in a Zoom meeting with the vice president of supply chain sustainability,” he says. “It's happening all the time.”

For example, a topic of discussion at recent shareholders’ meetings for both General Motors and Tesla was whether the companies should develop policies about sourcing minerals from deep-sea mining. Neither company currently uses minerals, such as nickel and cobalt, extracted from the ocean floor, but that could change as demand for electrical components and batteries in cars increases.

A letter-writing campaign or a conversation with an executive can not only move the needle of progressive action, but they could also make people feel less helpless about overwhelming problems like climate change. “I feel like every little bit helps,” Shalit says. “We have a lot of allies. People like to feel good about their work.”

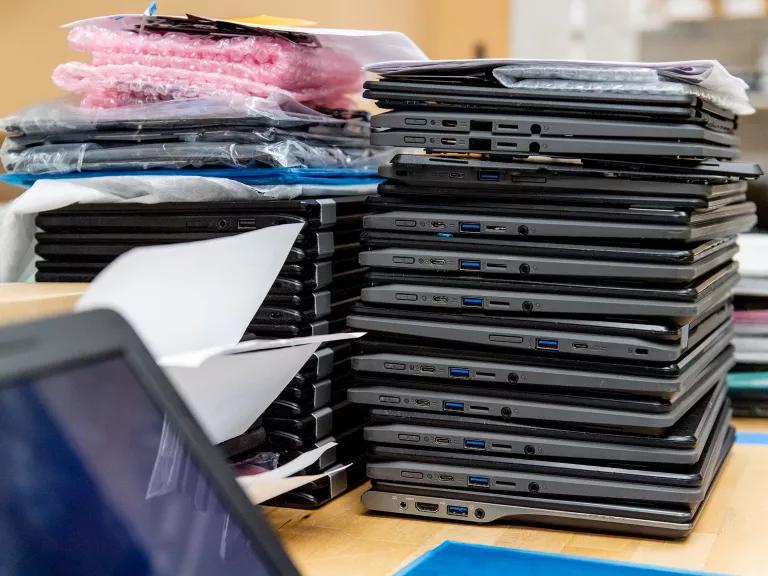

A stack of broken Chromebook laptops at Cell Mechanic electronics repair shop in Westbury, New York

Johnny Milano/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Putting your mouth where your money is

When it comes to publicly traded companies, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) offers shareholders another avenue to prompt companies to act. The agency’s 14a-8 rule allows shareholders to file a proposal that would then appear in a proxy, or vote, that is sent to all shareholders.

Anyone, or any group of investors—with $2,000 in shares held for at least three years, $15,000 for two years, or $25,000 for a year—can file a shareholder proposal. (While investments in mutual funds do not qualify, equity portfolios do.) A company can try to argue that a certain proposal doesn't meet the SEC rules, but ultimately, the SEC decides whether a proposal qualifies for inclusion in a proxy. Public concerns outside of business norms—say, a company’s greenhouse gas emissions or its pesticide use—could, and do, qualify.

“If you care about an issue like climate change, you really should try to find a good template, a proposal that somebody else filed, that's already gotten through the SEC,” says Sanford Lewis, an attorney who has been working with shareholders for two decades. That way, the proposal is more likely to be put on the proxy and brought to shareholders’ attention. A number of organizations also help investors navigate the proposal process, such as As You Sow, a nonprofit focused on corporate social responsibility; Ceres, a nonprofit advocacy organization; and the Interfaith Center on Corporate Responsibility, an investment company.

Sometimes, the mere suggestion that an investor may submit a proposal can lead a company to hold negotiations to address the issue before it even goes up for a vote. Otherwise, if a certain percentage of shareholders end up voting for the proxy statement, the company is then expected to act on the issue by its shareholders. Take what Microsoft investors did with a right-to-repair policy. Last year, more than 400 million people who used Microsoft’s Windows 10 on their computers weren’t able to run Windows 11 due to missing hardware features on older devices. The company wasn’t going to provide security updates for its earlier software, which would have then made all those computers obsolete. Shareholders filed a proposal and the company agreed to extend the security update for the following three years (until October 2025).

A similar situation occurred with Google’s Chromebooks, 100 million of which were headed to the landfill because they couldn’t get security updates. When investors and organizations brought attention to the issue and submitted a proposal, the company changed its policy and kept the devices in service.

And what happens if the company decides not to address the shareholders’ concerns? Even then, Lewis says, the process is still worthwhile. “The process of educating investors and possibly getting the attention of the management of companies—those are also benefits,” he says. Some companies need reminders that ignoring a majority of their shareholders on things that they care about comes at a price. “The shareholders,” Lewis continues, “might collectively decide to make some changes at the company, including running people for the board, voting against board members who are up for re-election, and voting against pay packages and other consequential actions of that ilk.”

The bottom line

Sustainability of the environment can often bring sustainability to a business. The World Economic Forum reported in 2022 that more than half of the total gross domestic product worldwide relies on nature and the ecosystem services it provides. Over the long term, it behooves any company that relies on natural materials (whether trees for toilet paper or lithium for EV batteries) to not deplete them.

Consumers are also increasingly looking for more accountability and transparency from the brands they choose. A 2020 report from the consulting company Deloitte found that more than 40 percent of respondents from six countries said that they had changed buying habits based on environmental concerns. Looking beyond self-reported preferences to actual consumer behavior, a study published last year by the consulting firm McKinsey & Company and consumer data company NielsenIQ showed that creating sustainable and socially responsible products is a solid business decision because sales of goods with those claims tended to grow 8 percent more than those without.

As logic would follow, greenwashing—a deceitful practice in which companies promote misleading or false pro-environment claims about their actions or products—could also pay off. Again, this is where consumers and investors can hold companies to account.

During Climate Week NYC in September 2022, Rainforest Action Network, Friends of the Earth U.S., and Sum of Us held rallies outside of corporate offices, including the headquarters of BlackRock, TIAA, and Colgate-Palmolive to denounce their failure to meet commitments against deforestation.

Erik McGregor

Corporate social responsibility: A good place to start

Getting companies to think bigger and be more responsible is critical, but corporate policies shouldn’t stand alone in the protection of natural resources and the environment. “Corporations have to be part of the solution because they're incredibly influential in public policymaking, and they're incredibly influential as drivers of the global economy,” says Vinyard. They often have a seat at the table in everything from major United Nations climate and biodiversity summits to community board meetings.

“But voluntary measures are never going to be the only solution. They have to go hand in hand with government policy as well.”

For example, just last year, the European Union passed the deforestation regulation, a law that states that certain products sold in the E.U. cannot contribute to deforestation and forest degradation. According to S&P Global, the law will likely “reconfigure trade and supply chains across deforestation-linked commodities over the next decade.” Depending on how the law is implemented, a broad range of companies, including those that make toilet paper, could have to disclose their sourcing and modify their practices.

By stepping up now, Kimberly-Clark could not only end up doing a solid for climate and biodiversity but also protect its bottom line.

Tell Procter & Gamble to stop flushing our forests!

Industrial clearcutting for forest products like P&G’s Charmin toilet paper is destroying more than one million acres of the boreal forest each year. Tell P&G President & CEO Jon Moeller enough is enough.

How to Lobby Your Legislator

What Biden Should Get Done on Day One (or Close to It)

How to Make an Effective Public Comment

How to Lobby Your Legislator

What Biden Should Get Done on Day One (or Close to It)

How to Make an Effective Public Comment

How to Lobby Your Legislator

What Biden Should Get Done on Day One (or Close to It)

How to Make an Effective Public Comment

How to Lobby Your Legislator

What Biden Should Get Done on Day One (or Close to It)