What Do “Better” Batteries Look Like?

They’re not only stronger and longer-lasting. To fuel the clean energy economy, they also need to be sustainable.

An electric vehicle owner uses an app to monitor its charging progress in a parking lot in Cold Spring Harbor, New York, on April 6, 2023.

Nicole Millman for NRDC

For three weeks this summer, President Biden and members of his administration went on the road. In 20 states, from Hawaii to Vermont, they spread the word about the more than a trillion dollars’ worth of investments in agriculture, manufacturing, health care, and—the road trip’s real headliners—clean energy and infrastructure.

During her weeklong tour through the southeastern corner of the country, Secretary of Energy Jennifer Granholm opted to drive herself from stop to stop. Why? The car she drove runs completely on battery power, and over the next seven years, three of the states she visited—Georgia, North Carolina, and Tennessee—are poised to become major manufacturing centers for electric vehicle (EV) batteries. "We wanted to come to the South because employers are coming to the South," Granholm said while visiting a North Carolina lithium-processing plant that recently received a $150 million grant from the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). "I wanted to come to the South because the president is really interested in ensuring that every pocket of America benefits from this agenda."

So far, the Biden administration has invested nearly $3 billion in batteries. Last October, the DOE announced that it would be awarding $2.8 billion in grants—made available through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law—to boost the domestic manufacturing of batteries for use in EVs and the electrical grid. And just last month, the department announced that it would set aside $192 million to create an advanced battery research and development consortium while continuing to fund the Lithium-Ion Battery Recycling Prize, which was introduced four years ago to help build a market for technologies that would decrease American dependence on imported battery components. These steps toward improving our battery tech will be essential in achieving the administration’s goal of transitioning to a net zero emissions economy by 2050.

Mike Ferry, with the University of California, San Diego’s Center for Energy Research, shows a bank of lithium-ion batteries for grid energy storage at UCSD on September 16, 2022, in La Jolla, California. At the peak of heat wave season, these batteries were able to put 3,300 megawatts into the electricity grid.

Sandy Huffaker/AFP via Getty Images

Batteries, supercharged

Many of us already rely on batteries to keep our phones and laptops running smoothly, but batteries have much heftier roles to play in the fight against the climate crisis. In fact, they’re essential to the decarbonization of our energy and transportation sectors.

The grid helps electricity get to where it needs to be, but it doesn’t store energy. A fossil fuel like coal “stores” energy in its solid form, which can be burned on demand. This, however, not only leads to greenhouse gas emissions but also large amounts of harmful air pollution, often in low-income communities and communities of color. Meanwhile, the clean energy generated by solar and wind power must be used immediately—but peak demand doesn’t always coincide with peak sunshine or wind conditions.

This is where batteries come in. They give us the ability to store clean energy and the option to release it into the grid whenever needed. Large-scale battery systems would make renewable sources even more appealing, ultimately hastening their supplantation of dirty fossil fuels. Their potential is massive. But as a nascent technology, battery production for renewable power is experiencing some hiccups, including obtaining the necessary materials, manufacturing delays, and costs.

Yet by 2030, global grid-scale battery storage capacity could more than quadruple to about 135 gigawatts. Meanwhile, the International Energy Agency (IEA) projects that battery-powered EVs will account for more than a third of worldwide automobile sales.

In addition to battery tech and production, the next seven years are also going to be pivotal ones for the climate. If we're to limit global average temperature rise to no more than 1.5 degrees Celsius—as we must do to avoid the most devastating impacts of climate change—then the nations of the world need to cut our collective total greenhouse gas emissions in half by 2030. This is just one reason why the Biden administration is pouring so much investment into battery research and development.

More mining is not the only answer

The vast majority of batteries used for EVs and grid energy storage systems are currently lithium-ion batteries. In addition to their namesake metal, these batteries typically contain nickel, manganese, graphite, and cobalt. Mining for these components, when done irresponsibly, comes with steep costs to human health and the environment. Like any extractive process, lithium mining can have major impacts on the local communities, ecosystems, and water supplies. Indeed, the process is already driving an environmental crisis for communities of Chile, where mining companies extract lithium through the evaporation of brines beneath salt flats on the Atacama Plateau, depleting water supplies, affecting farming, and disrupting ancient cultural traditions for the region’s Indigenous Peoples.

Meanwhile, demand for the crucial metal is projected to grow fivefold by 2030—and already, lithium is getting harder and harder to come by. So by replacing the gasoline-dependent combustion engines in our automobiles with lithium-ion batteries, are we just trading one set of extractive problems for another?

Not as long as we lean into more sustainable ways to meet lithium needs, says Jordan Brinn, a clean vehicles and infrastructure advocate in NRDC’s Climate & Clean Energy Program. “With our current fossil fuel–based system, we have to constantly input mined and extracted materials into the system in order for it to continue functioning every day,” Brinn says. “But with electric vehicles, you just have to input materials into the battery once, and then the vehicle continues to work for the rest of its life. Then, even once the vehicle is retired, those minerals can be recycled and reused again and again in batteries for new EVs.”

Strategies for making battery production cleaner, safer, and less reliant on extraction are the subject of a recent report authored by Brinn. She calls for increased research and development of improved battery chemistries and designs that rely on more sustainable materials—for instance, replacing some of the graphite typically found in lithium-ion battery anodes with silicon, which would deliver improved performance at a smaller size. Both the DOE and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency should step up their efforts on this matter by directing more funding toward improving material efficiency in battery manufacturing. The report also urges making battery technology its own category in prize programs (such as the Green Chemistry Challenge) and in the various certification programs these agencies administer. They should also set recovery rate targets for battery recycling (as the European Union does) and require the recycling of all EV batteries. Meanwhile, some manufacturers are already phasing down cobalt in their next generation of batteries, a significant step in reducing the need for mining of the metal.

Still, battery production, even with vastly improved efficiency, may always involve some degree of mining. That means we need mining laws made for this century, not the 1800s, to ensure that environmental protections, as well as engagement with communities near mining sites (including obtaining community consent), are meaningful and effective. Modern regulations—essential components of a clean energy economy—must also include recycling of the minerals that we already have in existing batteries.

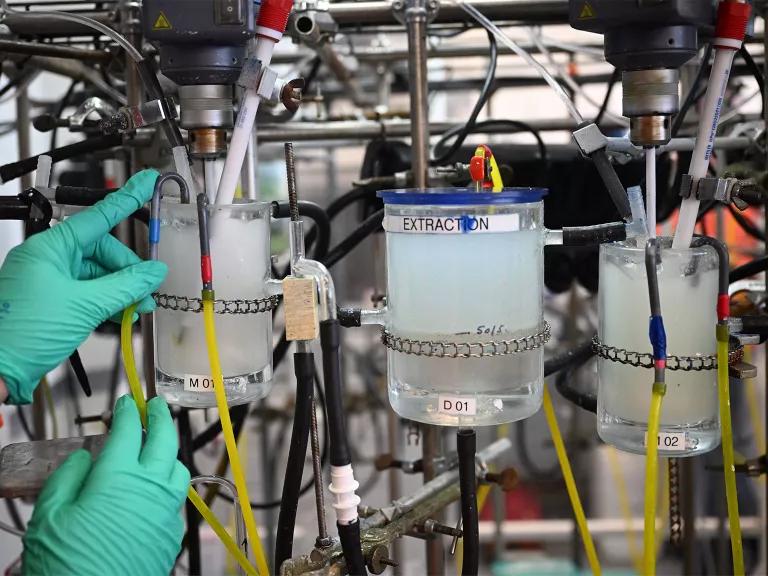

A lab technician manipulates an apparatus by which nickel and lithium are separated after being collected from recycled electric car batteries.

Emmanuel Dunand/AFP via Getty Images

EV batteries can help power our grid

Once we burn gasoline, that fuel is gone (burned up into the atmosphere), but EV batteries have a chance at a second life. After playing their part in helping to clean the transportation sector, they can do the same for the electrical grid. By serving as a means of stationary energy storage, our old car batteries could help ease stress on the grid during periods of especially high demand. Brinn says EV batteries are especially well suited for storing energy generated by rooftop solar systems, or for microgrids, which are power systems that typically service a small, geographically contained area. And repurposing these batteries, of course, reduces the need to extract the lithium and other materials found within them.

The need for better batteries is clear. And the technology is developing so quickly, and moving in so many different directions, that we may need to rethink our definition of what a battery even is. The word, for instance, may one day describe energy storage solutions that employ gravity and water. In the meantime, how we think of the power streaming into our grid and cars is ready for a recharge.

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

Transportation is the largest source of climate pollution in the United States.

Urge President Biden, the EPA, and the DOT to finalize the strongest possible clean vehicle standards!

Greenhouse Effect 101

What Are the Solutions to Climate Change?

What Are the Causes of Climate Change?