The Climate Math of Home Heating Electrification

A new study shows that a typical U.S. home can cut its heating-related climate pollution by 45 percent to 72 percent by swapping out a gas-fired furnace for an efficient, all-electric heat pump.

An HVAC technician working on a heat pump outdoor unit

iStock

The strong climate case for electrifying homes across America grew even stronger last week.

Researchers from U.C. Davis published a study in Energy Policy showing that a typical U.S. home can cut its heating-related climate pollution by 45 percent to 72 percent by swapping out a gas-fired furnace for an efficient, all-electric heat pump. And it’s true starting today, in every region in the country.

NRDC, a supporter of the study, asked U.C. Davis to look into this question for a couple of reasons. We often hear the concern that the CO2 emissions from generating electricity to power heat pumps make them too dirty today, and that we should wait to electrify—or swap out appliances that use fossil fuels in exchange for efficient electric models that can be powered by clean energy sources—until the grid gets cleaner. Other times we hear that electrifying too soon will exacerbate the impacts of hydrofluorocarbon (HFC) refrigerants, which cause climate change when leaked from appliances.

The new findings address both of these issues—plus the impact of the switch on fugitive methane emissions—and confirm that the time to act is now. Here are the results, in brief.

Carbon emissions

The biggest factor in the findings is the CO2 emissions from the electricity needed to operate the heat pump, as compared to the CO2 emissions of burning gas in a furnace. The study uses an EnergyPlus model to calculate annual energy use in an average single-family home (both a 2006 and a 2018 vintage, and the fractional results didn’t change appreciably). It compares a high-efficiency gas furnace to a high-efficiency heat pump (up to 10 HSPF, depending on sizing), the latter of which is the type of equipment we need to deploy to transition off of fossil fuels and maximize energy savings at the same time.

To turn energy use into emissions, the study takes a view of the grid based on how it’s expected to grow to meet our electrification needs, based on hourly data from the National Renewable Energy Lab (NREL)’s new Cambium dataset. This is called the ‘long-run marginal emissions’ rate and is a better way to look at future emissions than by evaluating current power plants. This approach considers that some new power plants will need to be built to serve new electrical loads as we electrify our heating, cars, and more. NREL’s Cambium data considers current federal, state, and local energy policies as well as the economics of gas, solar, wind, storage, and other generation resources, combining these factors to estimate what new generation will most likely serve that new load each hour of the year. The emissions intensity of the energy use follows.

Many states have already adopted policies to increasingly power their electric grids by clean energy resources. Those which haven’t will still see comparable transitions due to fast-falling prices of wind, solar, and storage. Taken together, this means that the average carbon footprint of new power sources is already much lower than that of gas power plants today and is continuing to drop rapidly.

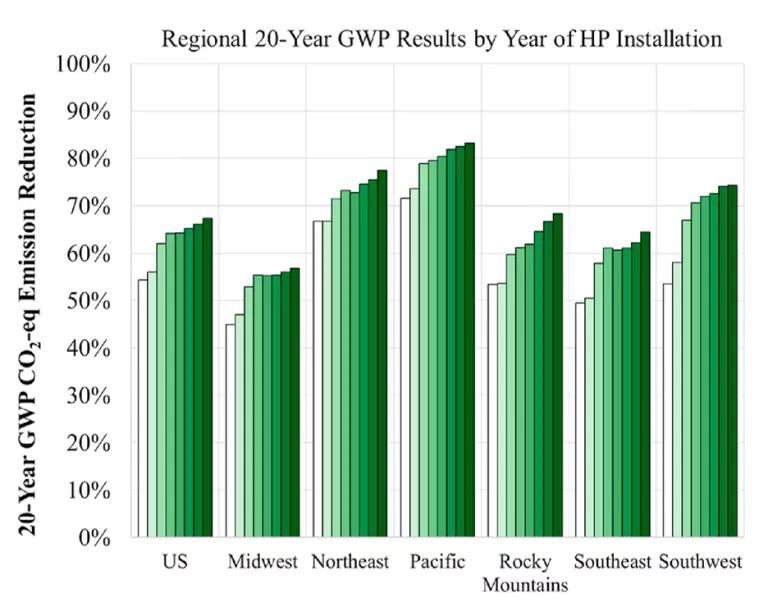

Regional overall results using 20-year GWP for methane and HFCs

For this reason, the study finds great life cycle climate performance for heat pumps. Here’s how it works: an average heat pump installed this year will last about 15 years, or until the 2030s. The grid will get much cleaner between now and then—President Biden’s plan is to bring the grid to 100% clean electricity by 2035, although the authors used Cambium’s “low renewable energy cost” scenario, which incorporates just 70% clean energy by 2050. Either way, the heat pump’s emissions will fall rapidly over the course of its life as the grid grows with clean energy resources. For these reasons, heat pumps are a climate-smart choice to install today.

Refrigerants

For HFC refrigerants there’s similar good news. First, a quick primer: HFCs are super-potent greenhouse gases—pound for pound, they’re thousands of times stronger than carbon dioxide—used in air conditioners and heat pumps to help create the cooling and heating effects.

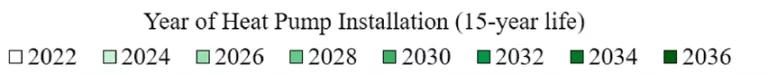

Overall U.S. average results using 20-year GWP for methane and HFCs

Because of HFCs’ environmental impact, the U.S. is embarking on an economywide HFC phasedown of 85% over the coming 15 years under the American Innovation and Manufacturing (AIM) Act. Under this program, heat pump manufacturers will soon be switching to models with climate-friendlier refrigerant alternatives. Refrigerant emissions that can be avoided are also expected to be reduced as HFCs become scarcer and therefore too expensive to waste. NRDC is also advocating for policies to increase end-of-life refrigerant recovery and promote leak repair. Like the study overall, these HFC refrigerant leak projections are specific to single-split heat pump units installed in residences, and do not speak to potential issues with other system types, such as larger, site-built residential and commercial systems that may have significantly higher leak rates.

The study assumes that for the next few years heat pumps continue to use current HFC refrigerants before transitioning to climate-friendlier refrigerants toward the middle of this decade. Both before and after this switch, the climate benefits of heating electrification far outweigh any potential incremental risk from refrigerants. Here’s why: most U.S. homes already have some type of air conditioning, which uses HFC refrigerant itself, connected to the furnace. In these cases, replacing a furnace with a heat pump is only “responsible” for the additional incremental refrigerant needed. Which isn’t very much, the authors find.

In sum, while we need to quickly move away from today’s HFC refrigerants, it shouldn’t impede a no-holds-barred push to electrify with heat pumps.

Methane

Finally, a sizable fraction of the benefit of the switch to heat pumps comes from reducing fugitive methane emissions associated with burning gas in a home furnace. Methane leaks at every stage of the supply chain, from the extraction well, to processing, distribution, meter, piping in the home, and at the burner itself. The study finds that when considering the climate impacts of methane over 20 years, methane leaks to the atmosphere contribute to climate impacts nearly as much as the methane that is burned for heat. This metric goes clearly in favor of heat pumps, even when considering that, for a time, some gas will leak on its way to a powerplant to power the heat pump. This effect diminishes with the fast-growing share of renewable energy sources.

Taken together, the numbers clearly show it’s time to electrify our heat. Overall, the study’s population-weighted average of 99 American cities shows a 53-67 percent reduction using a 20-year global warming potential (GWP) for HFCs and methane, a 44-60 percent reduction using a 100-year GWP, and a 38-53 percent reduction for CO2 alone (i.e., excluding the results for HFCs and methane, although we don’t advise doing so).

As you might expect, the emissions reductions are best in the Pacific and Northeast regions, which have fairly clean grids already. But the results are remarkably consistent across regions, and no single major climate zone in the country shows less than a ~45 percent reduction using 20-year GWP values. Some regions start as high as 72 percent reductions for units installed today.

So what’s next?

It’s time for policymakers in every state and in Washington, D.C., to mount a full court press to get heat pumps deployed into our homes and buildings. A good first start would be the incentives for heat pumps in the climate package in the Build Back Better Act, which Congress should pass. Consumers looking for a new AC or heating system should pick a heat pump if they can. The best time to do it is when it’s time for a new central AC, because it costs only a small fraction more to get a heat pump that provides both cooling and heating instead. This is an awesome deal for a brand new heating system that will save you money and your kids’ future. Replacing a burnt-out furnace is also a good occasion.

Heat pump manufacturers should gear up for an all-hands-on-deck transition to heat pumps, and specifically models that use climate-friendlier refrigerants, as soon as possible. It’s also a good time for manufacturers to make improvements to their models’ energy efficiency and limit additional refrigerant charge needed in their heat pump models.

And, of course, for the study’s forecasts to be true, we’ll have to continue making fast progress on our other climate goals: choosing efficient appliances, greening the grid, tightening methane leaks, and reducing the climate impact of HFC refrigerants. We have to work on these issues in parallel if we’re going to succeed in making the future climate impact of home heating as close to zero as we can.

This winter, take a moment to consider where the heat that keeps you warm is coming from. Let’s all find a better way.