Construction worker installing steel reinforcement bars

Understandably, Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton doesn’t delve deeply into late-18th century theories of political economy. But beyond his portrayals on stage, the nation’s first Treasury Secretary remains relevant today because his ideas can help the United States take on climate change.

Don’t worry – you don’t need to read Hamilton’s 1791 Report to Congress on the Subject of Manufactures before reading this blog. The basic idea is this: government incentives can play an instrumental role in creating new industries. In Hamilton’s day, that meant investing in manufacturing to exploit our abundant natural resources, but today it means investing in low carbon manufacturing, such as low-carbon concrete and steel for buildings, to protect those resources.

The construction and use of buildings contribute about 40 percent to global Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions, and slashing these emissions is thus essential to meeting our climate goals and protecting vulnerable communities. In addition to reducing energy use in buildings, we can significantly reduce the climate footprint of the building sector by reducing the amount of carbon-intensive materials used in building construction and increasing demand for low-carbon construction materials in buildings – in particular, concrete and steel.

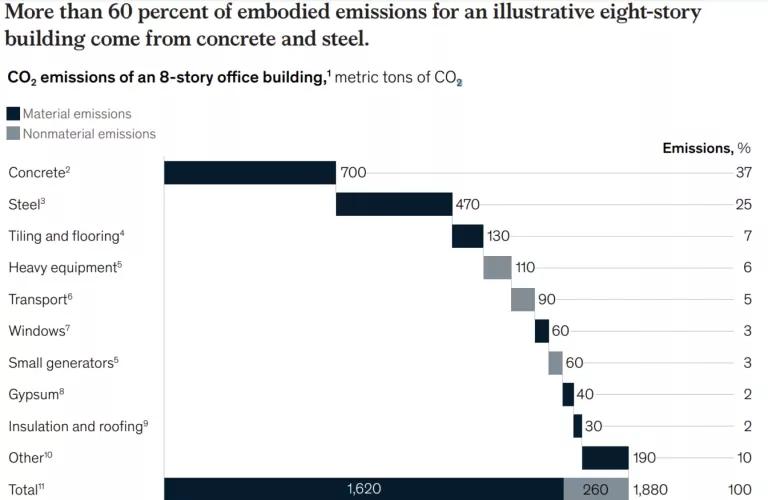

While building materials are typically a small fraction of the costs of building construction, they are often responsible for the bulk of its greenhouse gas emissions. As one example from McKinsey illustrates, in the context of an eight story commercial office building with a footprint of approximately 10,000 square feet, roughly 85 percent of the embodied carbon emissions would be from building materials. Of that total, about 37 percent would come from concrete and 25 percent from steel.

Chart showing promising emissions reduction potential from building materials

The good news is that because the federal government is such a massive customer in the building construction industry, its unique purchasing power can grow the supply chain for cleaner, domestically produced industrial building materials. This was our message in recent comments NRDC submitted to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development in response to the agency’s request for information on how to implement the Build America, Buy America provisions of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA):

HUD should adopt preference language for bids reporting the lowest emissions, as documented by EPDs [Environmental Product Declarations], assuming that they are otherwise comparable. Even without an explicit preference, requiring the use of EPDs for [IIJA projects] can help lower the emissions of projects funded by HUD.

Tools like Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs)— a best practice for measuring, reporting, and disclosing the carbon emissions generated during the production of industrial building materials—can help with both Buy American and Buy Clean preference programs. EPDs that conform to ISO standards, such as 14025, 14040, and 14044, require geographic information about the product to be gathered and independently reviewed. EPDs are available for a wide range of building materials, and recent examples from Washington State show that simply encouraging transparency on embodied carbon by requiring EPDs alone can reduce emissions for key materials, like concrete, by 20 percent.

Recent analysis suggests that deep emissions cuts in building materials – over 60 percent of embodied carbon for concrete and steel – could be available at a modest price premium, roughly 10-15 percent if the federal government commits to procuring these low-carbon alternatives. This commitment would encourage adoption of off-the-shelf solutions at scale and incentivize continuous innovation to deliver even deeper emissions reductions over time. The “government-wide” approach to climate change in EO 14008, complemented by IIJA procurement requirements, can work together to ensure that public dollars spent on constructing the buildings (and roads, bridges, and rail systems) Americans will rely on for years to come are also used to procure lower carbon construction materials and that manufacturers that invest in cleaner processes and products have a competitive advantage.

The Biden administration has already taken an important first step in this direction when the Government Services Administration (GSA) put out a new standard for low carbon concrete and environmentally preferable asphalt. When GSA requested information from concrete producers about the availability and cost of this lower carbon product, most respondents said that the lower-carbon alternatives to regular concrete cost “about the same,” which suggests that BAP could promote cleaner local products at no or low premium. Full implementation of IIJA procurement requirements can build on this progress, supporting the transition to low-carbon building materials.

Later this year, there will be an opportunity to repeat this message for the Notice of Proposed Rulemaking for climate-related updates to the Federal Acquisition Regulation required by Executive Order 14030, Climate-Related Financial Risk. Failing to apply the clear domestic preference laid out in IIJA and EO 14008 could thwart recent government-wide efforts to avoid the worst of climate change, which would disproportionately harm low-income households and communities of color. And investing billions in American infrastructure without using lower carbon concrete, steel, and other widely used industrial materials we and the world will increasingly rely on would be a major missed opportunity to invest in an environmentally sustainable U.S. supply chain.

Like Hamilton’s America, the clean materials industry is “young, scrappy and hungry,” and needs a coordinated federal approach to reach our climate goals.