Cut Carbon and Toxic Pollution, Make Cement Clean and Green

If the cement industry were a country it would rank as the world’s fourth largest GHG emitter.

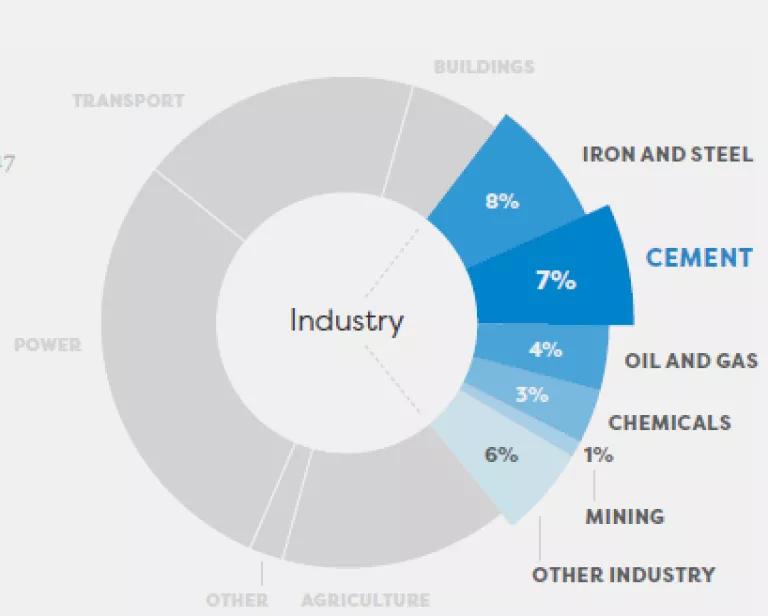

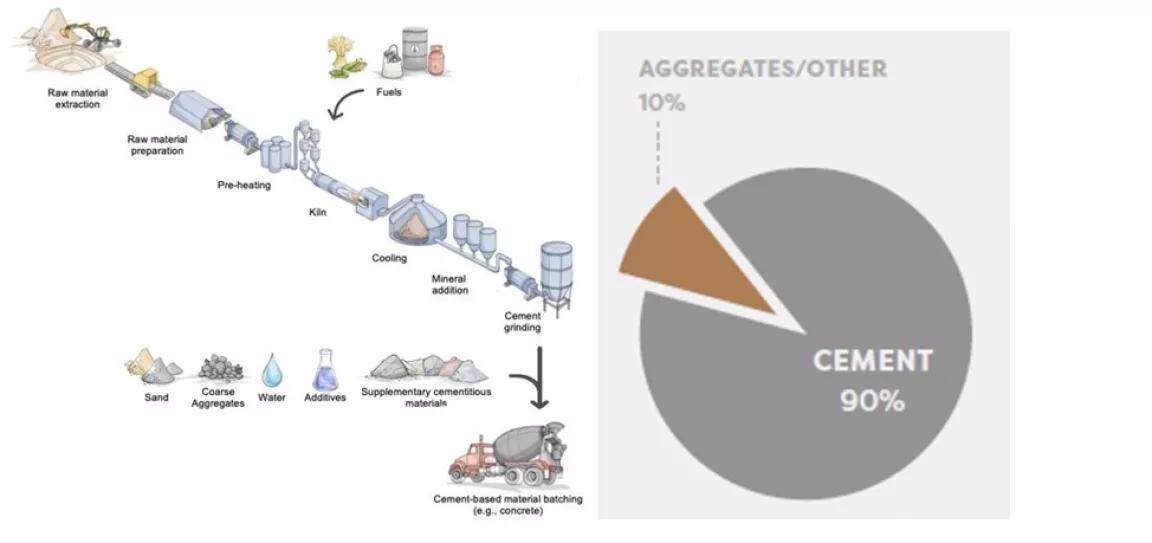

Decarbonizing cement plants is a critical part of reaching our climate goals. Cement is a key ingredient in concrete, which is the most widely used manmade material on the planet, and has few, if any, viable alternatives. Cement is incredibly dirty to produce: while it only constitutes 10-15% of concrete’s mass in a typical mix, it accounts for up to 90% of its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (Figure 1).

If the cement industry were a country it would rank as the world’s fourth largest GHG emitter, just behind China, the U.S., and India, responsible for roughly 7-8% of global CO2 pollution (Figure 2). Unless we take steps to decarbonize cement, this number is likely to increase as demand for concrete continues to grow.

Figure 2: Share of global CO2 emissions that come from cement production (2017 data).

Source: McKinsey

Making cement also emits a lot of dangerous air pollution that’s linked to an array of health harms; the cement industry is the third largest source of industrial air pollution such as sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides (NOx) and carbon monoxide.

Put simply, cleaning up the cement industry is critical to achieving our climate and health goals. But unlike the internal combustion engine, cement has no readily available replacement that can scale quickly enough to meet the imperatives of the climate emergency. Therefore, while reducing and substituting Portland cement using existing and emerging alternatives can and must be a priority, our dependence on the material will not only continue but likely grow in the coming decades—the timeframe most critical to climate action—as urbanization and infrastructure renewal ramp up. This makes it essential that we support innovation that ensures cement makers adapt to a clean future.

The good news is that momentum is growing in states and federally, as lawmakers seek smart approaches to curb emissions from cement production and leverage the government’s purchasing power to grow markets for cleaner alternatives. Industry carbon neutrality commitments and roadmaps are also proliferating. While some of the decarbonization strategies some cement manufacturers embrace are highly problematic from an environmental and/or health perspective, it suggests the industry knows it must articulate a plan to tackle emissions.

As these efforts move forward, a critical principle NRDC is advocating for is that reducing carbon pollution from cement must not come at the expense of local pollution.

Why making cement is so carbon intensive: combustion and process emissions.

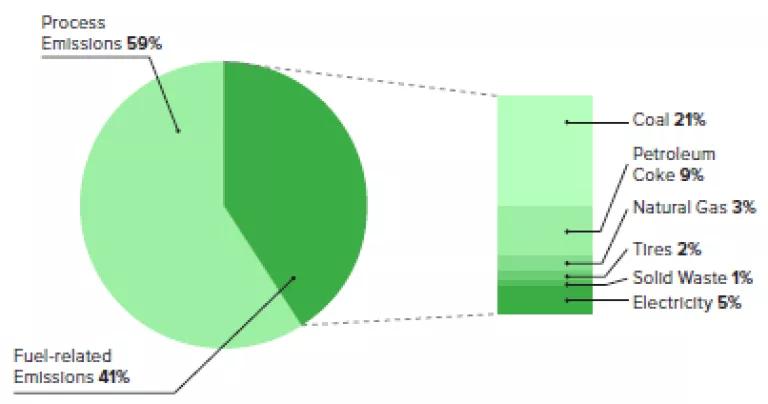

Two aspects of the Portland cement manufacturing process account for the vast share of its carbon footprint. Cement is overwhelmingly made by burning fossil fuels like coal and petcoke in cement kilns—akin to large furnaces—to heat limestone (raw material) to very high temperatures (~2,640°F/1,500oC). The heat induces a chemical reaction that transforms the limestone into clinker, which is then ground together with gypsum to form cement. Emissions from fuel burning are responsible for ~40% of the lifecycle CO2 emissions in cement (often referred to as the embodied emissions) (Figure 3). The other ~60% are the result of an unavoidable chemical reaction (calcination) that occurs when the limestone is heated, which releases CO2 from calcium carbonate in the limestone.

Figure 3. Sources of CO2 emissions in California’s cement industry in 2015.

Source: Global Efficiency Intelligence

Hazardous pollutants including criteria air pollutants and mercury are also released in both fuel-related and process-related emissions. These pollutants are linked to premature death, neurological problems, asthma, and other respiratory diseases.

Some alternative fuels promoted by industry come at an unacceptably high cost to communities.

Among the levers frequently cited for decarbonizing the cement industry is switching to solid waste fuels to displace fossil fuels in cement kilns. Unfortunately, these alternatives—often designated ‘low carbon,’ by the cement industry—include plastic and solid waste, such as tires (sometimes referred to as “tire derived fuel”), which emit highly dangerous, toxic pollution.

Regardless of what is being burned, waste incineration creates and/or releases harmful chemicals and pollutants, including air pollutants, such as cancer-causing benzene, PFAs, dioxins, and particulate matter, and heavy metals, such as lead and mercury, which cause neurological diseases, as our colleagues discuss here. These chemicals and pollutants enter the air, water and food supply near incinerators and get into people’s bodies when they breathe, drink, and eat contaminants.

Communities have fought toxic pollution from cement plants for decades, and NRDC has maintained that lowering carbon emissions can and must be accomplished without increases in toxic pollution. For these reasons, NRDC is opposed to powering cement kilns with fuels that release toxic pollution, including plastics and other wastes, as a decarbonization solution.

A key solution for decarbonizing cement is burning less of anything.

In addition to rejecting a shift to other toxic fuels, the status quo of burning gas and coal is also toxic. That’s why NRDC is advocating to:

- Use less cement—for example, by reducing the overspecification of cement in concrete mixes and encouraging the use of supplementary cementitious materials like ground glass pozzolans to partially replace cement in concrete mixes;

- Make cement kilns more efficient so they require less fuel; and

- Ultimately transition to truly cleaner fuels—for example, electrification from renewable sources if and where possible, as well as green hydrogen.

In addition, NRDC supports policies to ensure cement plants can access a suite of advanced technologies to zero out their emissions, including carbon capture, utilization, and storage options, as we discuss here. Carbon capture in cement is not a way to prolong combustion of dirty fossil fuels that can be replaced, but a way of addressing the largest share of process emissions that cannot otherwise be abated for a material we rely on.

Waste incineration is neither a good way to reduce climate pollution from cement, nor to deal with plastic waste streams.

Real solutions to managing plastic waste must focus on reducing waste at the source, manufacturing less plastic, and using effective and proven methods of mechanical and organics recycling—not incentivizing incineration of these materials.

NRDC advocates four areas of focus to reduce plastics pollution:

- Eliminate problematic and unnecessary plastics, such as single-use plastics;

- Innovate and scale up reuse and refill models;

- Create non-toxic materials to replace fossil-fuel derived plastics; and

- Scale up proven mechanical recycling or composting solutions.

Model cement and concrete decarbonization policies should reduce GHGs and toxic pollution.

Because state and federal governments are such large purchasers of concrete, public procurement policies are a powerful way to build demand for low carbon concrete—and, by extension, to incentivize using less and less carbon-intensive cement. Multiple state legislatures have passed or are actively debating low carbon concrete procurement laws for state-funded construction projects, including California, New York, New Jersey, Colorado, and Virginia. A key principle in this work should be to prohibit cement produced with dirty fuels from being included in state low carbon concrete specifications—in other words, from receiving ‘green’ credit for changes that may reduce GHG emissions but increase local air pollution.

But demand-side procurement policies are not the only lever available to policymakers committed to tackling the climate and public health impacts of the cement industry. NRDC will continue to advocate for a package of policies that includes incentives to reduce embodied carbon emissions in final concrete mixes; standards to directly decarbonize the cement industry on a trajectory consistent with state and national climate targets; and mandates to prevent increases in harmful pollution.

For example, in 2021, California enacted a new law that not only focuses on achieving net-zero GHG emissions associated with cement used within California no later than 2045, but also requires improvement in air quality and support for economic and workforce development for communities near cement plants. Other climate leadership states like New York should follow suit this year—demonstrating the win-win of climate and public health benefits.

.jpg2352.jpg)