Causes and Effects of Lead in Water

How this harmful neurotoxin got into our taps and what it’ll take to get it out.

Marcelina Pedraza at her home in the East Side neighborhood of Chicago on June 3, 2021. Pedraza had her water tested for lead in January 2020, and lead was present in three samples.

Taylor Glascock for NRDC

Tough yet malleable and easy to bend and work with, lead became the chosen metal for water pipes long, long ago—a use, in fact, that dates back to the ancient Romans. Today we know that this material doesn’t belong in our homes, and certainly not in our drinking water systems. Lead is notoriously dangerous, with medical and public health experts agreeing that there is no safe level of lead in the human body. Additionally, this potent, irreversible neurotoxin is especially harmful to babies and young children.

In 2016, Flint, Michigan, made headlines around the world as it was revealed that blood-lead levels in children (in areas where lead in water had increased) had nearly doubled since the city started pumping in drinking water from a new source without properly treating it—a hasty, cost-saving move. The inadequate treatment and testing of the water resulted in a series of major water quality and health issues for Flint residents. These issues were chronically ignored, overlooked, and discounted by government officials even as complaints of foul-smelling, discolored, and off-tasting water mounted for 18 months.

The Flint water crisis represented government failure at the city, state, and federal levels. And it forced a national reckoning with the vulnerability of the nation’s aging water infrastructure.

America’s lead pipe problem

An advertisement placed by the National Lead Company in National Geographic magazine in 1923 touted the safety of having lead pipes in homes.

Photo courtesy U.S. National Library of Medicine

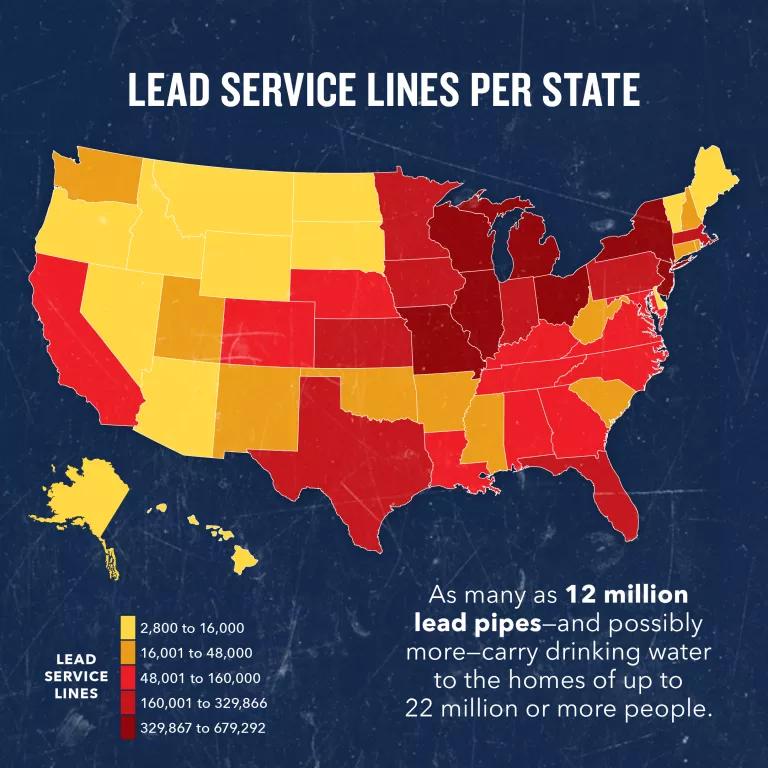

Between 1900 and 1950, a majority of America’s largest cities installed lead water pipes—with some cities even mandating them for their durability. And because lead pipes can last 75 to 100 years, the legacy of lead pipes lives on today. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has estimated that there are currently 6 to 10 million lead service lines across the United States—and a 2021 NRDC survey found that there may be 12 million or more of these lead pipes.

Since the revelations in Flint, dozens of cities have been found to have dangerously elevated levels of lead in homes, schools, and daycare centers. High lead levels have been found in tap water in Baltimore, Chicago, Detroit, Milwaukee, Newark, New York, Pittsburgh, Washington, D.C. One NRDC analysis found that between 2018 and 2020, 56 percent of the U.S. population drank from water systems with detectable levels of lead.

The issue isn’t limited to cities. A survey by NRDC shows that lead service lines (water pipes in the ground) are likely in use in every U.S. state, and that many states and utilities do not know where their lead service lines are. This means their inventories may grossly underestimate the number of lead lines, sometimes by millions.

Causes of lead in water

So how does the lead get into our tap water? The simplest explanation is that when plumbing pipes and fixtures containing lead corrode, the lead can dissolve or flake into the water that flows from our faucets. You can’t see, smell, or taste lead, so even water that runs clear can contain it.

Corrosion of lead plumbing

Corrosion is a chemical reaction that happens between the water and the lead-containing plumbing fixture. Certain qualities of the water—for example, acidity and certain types of dissolved minerals in the water—can play a major role in that reaction. Other factors include water temperature, age and wear of the plumbing fixtures, and the length of time water sits stagnant in the pipes.

Common sources of lead plumbing include:

- Lead service lines: Service lines are the pipes that connect homes and buildings to the water main in the street. Copper is a safer alternative.

- Lead-soldered joints: Solder is a metal alloy that helps connect pipes in household plumbing. Congress amended the Safe Drinking Water Act to mandate “lead-free” solder for plumbing after 1986, but homes built before this time may still contain lead solder.

- Plumbing fixtures: Until 2014, regulations allowed manufacturers to use significant amounts of lead in the construction of faucets, valves, and other plumbing fixtures. Even more recently made fixtures (including brass, plastic, and chrome-covered), are allowed to contain reduced lead levels, yet still be misleadingly labeled “lead-free.”

Inadequate or inappropriate municipal water treatment

The EPA requires water utilities to conduct water-quality monitoring, to use corrosion-control treatments, and to monitor and treat source water as needed to provide safe drinking water. While Flint is the most infamous example, dozens of other cities are failing to properly treat their water. For example, in 2001, Washington, D.C., changed its disinfectant from free chlorine to chloramines without first studying the potential impact. The chloramines made the water far more corrosive, and tragically, extremely high lead levels pervaded the city. (D.C. is still working to fix its lead problem today.)

Anti-corrosion chemicals can be used to prevent lead and other metals in the pipes from leaching into the water. Corrosion inhibitors like zinc orthophosphate are used by water systems to coat the inside of lead pipes and fixtures with a thin, protective layer that reduces leaching and flaking.

Health effects of lead in water

Even the ancient Romans understood lead can make you sick. Today, health experts including scientists at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Academy of Pediatrics agree that there is no safe level of exposure. While it’s toxic to everyone, fetuses, infants, and young children are at the greatest risk for lead poisoning because their brains and bodies are rapidly developing and more easily absorb lead than do those of older children and adults. But adults are also at risk, particularly from cardiovascular disease due to lead exposure. As levels increase, these harms become more severe.

To the cells in our bodies, lead looks a lot like the mineral calcium, which is vital to healthy brain development and function, strong bones and teeth, and a healthy cardiovascular system. As a result, lead that has been absorbed or ingested can travel through our bodies and cause problems in our bones, teeth, blood, liver, kidneys, and brain, disrupting normal biological function.

Lead poisoning

High levels of lead exposure can be serious and life threatening. In children, symptoms of severe lead poisoning include irritability, weight loss, abdominal pain, fatigue, vomiting, and seizures. Adults with lead poisoning can experience high blood pressure, joint and muscle pain, difficulty with memory or concentration, and harm to reproductive health.

Jeremiah Loren, 12, rinses with bottled water after brushing his teeth at home in Flint, Michigan, on January 20, 2016.

Brittany Greeson/The New York Times/redux

Even moderate to low levels of lead exposure—which might cause subtle symptoms—can still produce serious harm. Health effects include hearing loss, anemia, hypertension, kidney impairment, immune system dysfunction, and toxicity to the reproductive organs. Low levels of exposure can interfere with thought processes and lower children’s IQ and also cause attention and behavioral problems—all of which affect lifetime learning. Children with serious lead-related neurological impacts are less likely to graduate from high school and are more prone to delinquency, teen pregnancy, violent crime, and incarceration.

Lead exposure and environmental justice

Researchers with NRDC, Environmental Justice Health Alliance, and Coming Clean have analyzed EPA data and reported a correlation between a community’s racial composition, bad water, and inadequate response to violations. Another report has shown that wealthier white communities, who can afford to pay for pipe removal, are more likely to benefit from lead pipe removal programs than are low-income communities of color.

Lack of access to clean water is a major environmental justice issue—and its persistence proves that we need to actively address these barriers.

In a demonstration outside the Prudential Center in Newark, New Jersey, protesters bring attention to the city’s water crisis.

Karla Ann Cote/NurPhoto/Getty Images

What the United States can do to speed up the transition from lead pipes

President Biden has called for the removal of 100 percent of the lead service lines in the United States and, at the end of 2021, signed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) into law. Also known as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, it includes a $15 billion commitment to replace lead pipes that connect homes to drinking water mains, as well as an additional $11.7 billion that can be used by communities for any drinking water infrastructure priority, including removal of lead service lines if a state decides to spend the funds on that.

There’s still much more work to be done. Congress and the Biden administration should also strengthen the Lead and Copper Rule (LCR)—which regulates the monitoring and control of lead in drinking water—to require strict, science-based standards and lead pipe replacement as quickly as possible. The latest revisions of the LCR, published in January 2021 by the EPA, was unlawfully weak and would leave millions of lead pipes in use, exposing tens of millions of Americans to lead. The revised rule also included only minimal testing requirements for drinking water fixtures in schools and child care centers—failing to protect children from a major potential source of lead.

Workers with the East Bay Municipal Utility District replace a water pipe in Walnut Creek, California.

Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

Most important, the cost of removing these lead pipes should not fall on the shoulders of homeowners. By investing the billions of dollars needed for infrastructure improvement, Congress can create jobs while ensuring equitable access to lead-free water.

Thanks to the work of coalitions that emerged from the Flint water crisis, the state of Michigan now has the strongest LCR in the country—paving the way to full replacement of lead services lines and other precautions to reduce exposure. Other states, like Illinois, are following suit. To prevent future disasters like the one in Flint, the EPA should mandate even stricter protections. Requirements should include an at-the-tap standard and filtering, treating, testing, and fixing the problem—whether in our homes, businesses, schools, or child care centers.

How to find out if lead is in your water

The first thing you should do is learn all about your water. The EPA requires all community water systems to prepare a Consumer Confidence Report (often called an annual drinking water quality report or right-to-know report) for customers. The report tells you where your water comes from and what’s in it. And if it’s not available on the EPA website, call or check the website for your water utility.

To find out if you have lead pipes, check out NRDC’s step-by-step guide to see if you have a lead service line. You can ask your water utility if your local community has public records about drinking-water service lines. Your water supplier may also have information about your home or area. Or ask a licensed plumber to determine if your plumbing fixtures or the pipe that connects your home to the water main are made from lead.

If your water comes from a well or other private supply, check with your health department or with a local water utility that uses groundwater to learn more about any contaminants of concern.

How to test for lead in drinking water

Some states and cities offer free water testing for lead; check with your local health department or water utility. You can also use an independent testing laboratory, such as Healthy Babies Bright Futures, which offers below-cost kits to community groups, or check the EPA website to find a list of certified labs that can perform the testing for a fee for a single lead test of about $50.

Be sure to collect multiple samples of your tap water and avoid turning on the water in your home for at least six hours prior to sampling. There may be varying instructions from your city or lab on how to collect the samples, but collecting this “pre-flush” sample is a must. This EPA guide offers more information about home water testing.

How to reduce your exposure to lead in drinking water

There are a number of ways to reduce your exposure and remove lead in your tap water.

- Use only cold water for drinking. Warm or hot water is more likely to contain elevated levels of lead.

- Remember: Boiling contaminated tap water does not reduce or remove lead. Doing this may only make it worse by concentrating the lead content.

- Regularly clean your faucet’s screen (also known as an aerator).

- Flush out stagnant water from the pipes by running your faucet for a few minutes or more. Some city websites provide additional instructions for areas known to have lead service lines.

- Use a water filter that is certified to remove lead. Certifying agencies include NSF International and the Water Quality Association (WQA). Look for filters that say they meet Standard 53.

In addition, there are several common home water-treatment methods—products which can be purchased at major hardware stores:

- Carbon filter: Activated carbon filters have a lot of surface area where lead particles can attach. They come in three main categories: pitchers, end-of-faucet, and under-the-sink.

- Reverse osmosis: This method uses an electrically charged membrane to separate water from dissolved solids including lead.

- Water distillation system: Distillation heats water into steam. The water vaporizes, and minerals and other solids (including lead) are left behind. The system collects the purified evaporated water.

Regardless of the method you choose, certification that the filter meets NSF or WQA standards for lead removal, and proper maintenance and upkeep, like replacing filters, are critical.

Finally, you can have your lead pipes removed. If it’s the pipe that runs from the water main to your home that contains lead, often the utility will take the position that it’s the responsibility of both the utility and the homeowner. Homeowners can contact their water system to learn about how to remove the lead service line. That said, here’s an important caveat: If you find that the service line contains lead, do not remove that pipe yourself. The city or an experienced and approved contractor should remove and replace the entire length of the lead service line, because replacing only part of it could cause lead levels to increase. Even after your lead service line is replaced, your water should be filtered for at least 6 months, since lead particles can adhere to your indoor plumbing for several months and can be released into your tap water.

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

Millions of Americans drink tap water served by toxic lead pipes.

Tell the EPA we need safe drinking water!

Tell the EPA we need safe drinking water!

There is no safe level of lead exposure. But millions of old lead pipes contaminate drinking water in homes in every state across the country. We need the EPA to do its part to replace lead pipes equitably and quickly.

What Can We Do to Fix the Drinking Water Problem in America?

Is Water a Human Right?

Lead by the Numbers