Colorado River Basin Tribes Address a Historic Drought—and Their Water Rights—Head-On

Their growing inclusion in the region’s water management will likely prove priceless.

A pivot-irrigated corn field at the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe Farm & Ranch Enterprise

A warm breeze slips down from Sleeping Ute Mountain, stirring fields of alfalfa and corn across the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe Farm & Ranch Enterprise in the arid flats of southwestern Colorado. The state-of-the-art farm, with its ultra-efficient drip irrigation, satellite-guided tractors, and sought-after Bow & Arrow brand of non-GMO cornmeal, is an intense source of pride for the 2,000-member Ute Mountain Ute Tribe. It’s also an important income source for its 553,000-acre reservation in the Four Corners Region, where Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah meet.

In normal times, the enterprise employs several dozen tribal members and distributes more than $1 million in paychecks annually. But these are not normal times. The epic Southwest drought, whose severity has been fueled by climate change, has hit the farm hard. Today, it scrapes by on just 10 percent of the water normally flowing along a clay canal from the McPhee Reservoir. As a result, corn harvests have been cut by 75 percent, and half of the 50-person workforce, mostly tribal members, were laid off. Overall, the tribe lost an estimated $4 million to $6 million in the last year alone. Now, longtime general manager Simon Martinez squeezes everything he can from a drop of water. “We can’t do any more than that,” he says.

To the Ute Mountain Ute, grappling with its water supply is an ongoing challenge. Despite having senior water rights dating back to 1868, when the Kit Carson Treaty created the reservation, the tribe received none of its rightful water for decades as non-Native settlers dammed rivers and diverted flows. And like many tribes across the Southwest, it still struggles to properly quantify and settle some of the water claims already validated by a long stream of court decisions. Even when tribes have been able to secure their water rights, they have often lacked the expensive infrastructure for getting it to their reservations, which means their water gets used, without payment, by non-native groups. And whenever states have wrangled over distribution of Colorado River Basin water, as they have during this drought, Native Americans were generally left out of the conversation.

But more recently, that’s begun to change.

The Southwest drought has actually led to a push by tribes to address long-standing water supply issues and with good reason: Of the 30 Colorado River Basin tribes, 22 already have federally recognized rights to about a quarter of the river’s water. Some, such as the Ute Mountain Ute, still have claims awaiting settlement, which means that the percentage of water going to tribes is likely to climb. Most of the claims date back to the creation of their reservations in the 19th century, making tribes among the river’s most senior claim holders as well as some of the most historically judicious users. Given those facts, their inclusion in shaping ongoing water policy is essential to both advancing environmental justice and to facing the ongoing effects of climate change on the region.

It’s time for Native Americans to be part of that discussion, says Ute Mountain Ute Chairman Manuel Heart. “But we need to prioritize our own needs first, our water use and future endeavors, and then we can work in partnership. We are willing to help out areas where we can and create a better management plan.”

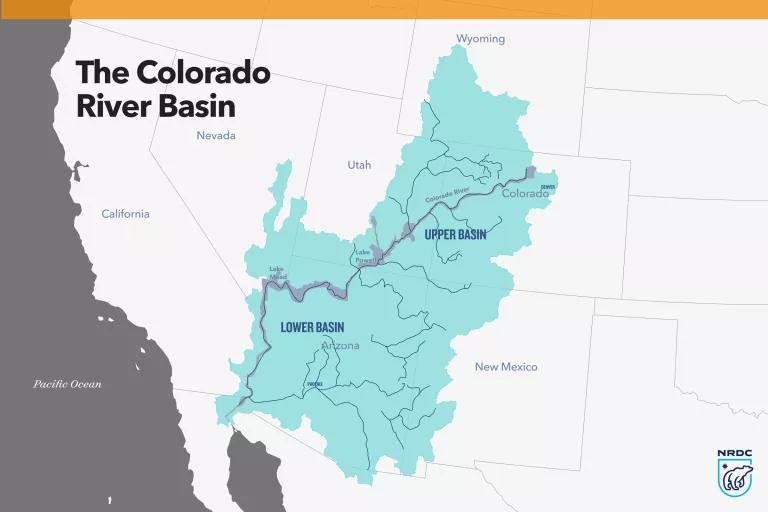

The water crisis and the Colorado Basin

Certainly, the stakes could not be higher for the troubled Colorado River Basin. The 246,000-square-mile watershed typically provides water for more than 40 million people across seven western states and supports a $15 billion agriculture industry. But its storage reservoirs, Lake Mead and Lake Powell, are currently at 27 and 25 percent of capacity, respectively. That’s a historic low. If the drought continues and they get much lower, water simply won’t flow out, creating a situation known as “dead pool.” That would also shut down hydroelectric generators currently providing enough power for 2.5 million homes.

In a way, many of the basin’s fundamental water problems can be traced straight back to the 1922 Colorado River Compact, which first defined how river water would be shared between the states and shaped much of the federal infrastructure funding that followed. Tribes were not included in this negotiation nor was it clear how much water they were guaranteed. (That came later via a U.S. Supreme Court decision.) The apportioning of the river was also based on the overly optimistic premise that nearly 20 million acre-feet of water would flow through it each year. (An acre-foot is enough to cover an acre of land in one foot of water.) In reality, average river flows hovered around 15.2 million acre-feet, dropping down to 12.5 million feet as the drought took hold two decades ago.

Since then, the region’s water needs have continued to increase along with its population. Arizona, California, Nevada, and New Mexico—all primarily dependent upon an already over-allocated Colorado River—are home to some of the nation’s fastest-growing counties.

Then, there are the impacts of climate change. The drought has generated the driest two decades in the region in at least 1,200 years, and experts estimate that 42 percent of its severity can be attributed to human-related causes. This has led to increased wildfires and changing weather patterns, which have, in turn, impacted culturally vital plants. It’s an unsustainable situation that now has states wrangling over agonizing water cuts.

“Everybody's realizing that we're all at risk,” says Sharon Megdal, director of the University of Arizona Water Resources Research Center. “If Lake Mead goes down to dead pool, and water can't flow, it doesn't matter what the priority of the Yuma farmers is. It doesn't matter what the priority of the Imperial Irrigation District farmers is. We're all in this together. And that includes the tribal communities.”

A call for change

Tribal leaders have had to fight for their inclusion. For the first time, in 2019, they played a central role in crafting the Colorado River Basin Drought Contingency Plans, which prescribed a series of water cuts among most of the states the river serves. But then the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (BOR), which oversees the river, ordered states and tribes to reach another agreement by August 15 of this year, with a goal of conserving up to four million more acre-feet. In response, 14 of the Basin Tribes stated they were largely not consulted in the ongoing process—yet again. The deadline passed without an agreement. And, on October 28, the U.S. Department of the Interior (parent agency to the BOR) announced that it could soon impose its own cuts on the states.

That failure to reach a consensus illustrates how broken the old system is, says Jay Weiner, a water attorney for southeastern Arizona’s Quechan Tribe and a leadership team member of the Water & Tribes Initiative, which works to expand tribal policymaking influence. “Everyone has realized that the historical arrangements are not working. It has compromised the river and fundamentally needs to be rethought.”

Devising new approaches has been the work of groups like the Ten Tribes Partnership, a coalition led by Chairman Heart that recently participated in an annual conference of the high-powered Colorado River Water Users Association. Tribes also created the Colorado River Basin Tribal Coalition as a strategy forum. And last year, the consortium known as the Inter Tribal Council of Arizona (ITCA) signed a memorandum with the BOR to ensure participation in river management negotiations. In a statement, ITCA President Bernadine Burnette called the agreement a “historic step toward protecting the significant water rights and entitlements of ITCA member tribes.” More recently, the Colorado Basin Tribes sent a letter to the U.S. Secretary of the Interior, Deb Haaland—the first Indigenous person to serve as a cabinet secretary—seeking to further clarify tribal involvement. “Our perspective, which is undoubtedly shared by others in the basin, is that we should all be working together as soon as possible,” the letter stated.

Aside from proper involvement, there is the traditional Indigenous reverence for water that holds lessons for an increasingly thirsty Southwest. Some, such as the Ute Mountain Ute, use extremely efficient farming methods, from computerized irrigation systems to water-stingy pivot sprinklers. Others, such as the Gila River Indian Community near Phoenix, demonstrate how wise use of water can result in habitat restoration, highly effective groundwater recharge programs, and a revival of water-related cultural practices. Today, that wisdom is needed more than ever.

Still, it’s too soon to know whether the tribes’ guidance will be honored, according to Heather Tanana, a member of the Navajo Nation, and an assistant professor at the University of Utah’s S.J. Quinney College of Law. In an e-mail, she writes that the tribes are “being very vocal about the need and expectation for tribal inclusion going forward. But what does actual tribal involvement mean and look like? I don’t think we quite know yet.”

There are already examples of how that process has yielded mixed results. For instance, in recent years, several tribes have agreed to help the region by leasing a portion of their water allocations to non-Indigenous users. In 2021, the Gila River Indian Community and the Colorado River Indian Tribes also agreed to help bolster Lake Mead by leaving a combined 179,000 acre-feet of their allocations in the reservoir. But the Gila River Indian Community reversed course in August after states failed to meet the BOR deadline for agreeing to more cuts. Gila Governor Stephen Roe Lewis told reporters that his tribe “has been shocked and disappointed to see the complete lack of progress” in reaching a larger agreement. Then last month, incentivized by potential funds from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, the tribe announced that it would conserve its supplies, thereby freeing up some of its water to help maintain Lake Mead.

Of course, there are still tribes fighting just to resolve and protect their water rights. In November, the Supreme Court agreed to hear a case involving the Navajo Nation and its claims of the right to divert water from the Colorado River. The ruling will have huge ramifications for community members and their ability to access safe drinking water.

Acknowledging a history of betrayal, and building a better future

The work of these tribes to assert their influence is, at its most basic level, an attempt to correct a legacy of injustice.

Almost every issue they face is rooted in racist government policies that forcibly drove them off their ancestral lands and onto reservations, which are now proven to be more climate vulnerable. Then they were given water rights that were largely ignored for decades. They got no support to develop infrastructure to access that water, even as the federal government lavished funds on non-Indigenous water projects throughout the basin, heavily subsidizing those interests while delaying water rights negotiations.

The effects still linger. Many, such as the Ute Mountain Ute, have no way of getting their water to their reservations due to the very high costs of building delivery canals and installing pumps. On the nearby Southern Ute Indian Reservation, 15 percent of residents pay to have tanks of water hauled to their houses, while 40 percent of tribal members on the 27,000-square-mile Navajo Nation still lack running water in their homes.

Some restitution is finally coming, thanks to the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. It will inject $13 billion into tribal communities to begin addressing these deficits. The measure also includes $2.5 billion for water delivery infrastructure and $1.7 billion to fulfill Indian water rights settlements. Hopefully, the money will help at least 12 of those tribes—including the Ute Mountain Ute—finalize their water claims. And thanks to revenue from tribal casinos and gas and oil royalties, most of the tribes are able to hire top-notch water attorneys to ensure a proper resolution.

Still, the fact that they even have to fight for their water rankles Tanana. “It’s not like the tribes all of a sudden had those rights,” she says. “We’re still catching up from historic racism underlying systems of bureaucracy.”

It’s a lot to overcome. Nonetheless, Chairman Heart hopes the newfound appreciation for tribal rights will bring his people the water they need, for sustenance and for their souls. “Water is from our creator,” he says. “For human beings, for the animals that roam the lands, whether they are four-legged, two-legged, fish or plants, water is life.”

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

As Sea Level Rise Threatens Their Ancestral Village, a Louisiana Tribe Fights to Stay Put

In Planning for Climate Change, Native Americans Draw on the Past

Taking Care of the Food Workers Who Take Care of Us

As Sea Level Rise Threatens Their Ancestral Village, a Louisiana Tribe Fights to Stay Put

In Planning for Climate Change, Native Americans Draw on the Past

Taking Care of the Food Workers Who Take Care of Us

As Sea Level Rise Threatens Their Ancestral Village, a Louisiana Tribe Fights to Stay Put

In Planning for Climate Change, Native Americans Draw on the Past

Taking Care of the Food Workers Who Take Care of Us

As Sea Level Rise Threatens Their Ancestral Village, a Louisiana Tribe Fights to Stay Put

In Planning for Climate Change, Native Americans Draw on the Past