In Planning for Climate Change, Native Americans Draw on the Past

Across North America, Indigenous tribes and nations are consulting their traditional ecological knowledge to help prepare for a warming world.

The Umatilla River in northern Oregon

When the leaders of the Cayuse, Umatilla, and Walla Walla tribes gaze across the Umatilla River, a tributary of the Columbia in northern Oregon, they see their past, present, and future. Organized as the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation (CTUIR), the tribes have lived with the ebbs and flows of the river for millennia, as it provided them with clean water and once-abundant food sources, such as salmon. Now, as the tribes seek to prepare their lands and people for climate change, a large part of their effort is devoted to revitalizing the river, which has been struggling with pollution, rising water temperatures, and declining wildlife populations.

Similar to many climate strategies of Indigenous groups across the country, the confederation’s climate adaptation plan, finalized last year, draws on the tribes’ traditional ecological knowledge. This knowledge is acquired through an intimate, time-tested relationship with a particular landscape and the unique assemblage of plant and animal species dwelling there. And like any healthy relationship, it’s a two-way street.

“Reciprocity is a big concept that's really been missing in western land management,” says tribal member Eric Quaempts, director of the CTUIR’s Department of Natural Resources. “When you talk about things like sustainability, it's often just pictures of windmills out in the ocean. But the notion of reciprocity—that you have to give back to the system—is critical when you think about ecology.”

Giving back to go forward

The preservation of “first foods” is just one way that the CTUIR is building climate resilience, alongside efforts such as diversifying renewable energy sources on the reservation, addressing physical and mental health concerns within the community, and bolstering tribal sovereignty. Elk, deer, berries, roots, salmon, and other traditional foods are honored spiritually, through ceremonies, as well as physically, by nurturing their habitats. “These foods made a promise to take care of us,” Quaempts says. “We have a reciprocal responsibility to take care of them.”

For instance, take the recovery of salmon populations, which is a top priority in the Umatilla and throughout tribal lands in the Pacific Northwest. In the early 1800s, up to 16 million salmon and steelhead trout would return from the ocean to spawn in the Columbia River and its tributaries. But over the centuries, timber extraction, development, dams, pollution, and climate change combined to take a heavy toll on the salmon’s ability to thrive, and especially, to migrate. Between 1938 and 1971, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers constructed three Columbia River dams—Bonneville, John Day, and the Dalles—which killed juvenile salmon in their turbines and dramatically changed conditions in the river for migrating fish. By the 1970s, return rates were around a mere 500,000 fish. In the Umatilla, specifically, salmon had been locally extinct for 70 years before the CTUIR began their fish restoration work in the 1980s.

Tribes across the Northwest and Alaska have been working with regional communities to reduce water pollution from agricultural activities and to rejuvenate riparian areas through the planting of trees, which shade and help cool the water for temperature-sensitive species such as salmon. Some tribes operate their own fish hatcheries, like Washington’s Tulalip Tribes, who raise and release three species of salmon (Chinook, chum, and coho).

And through collaborations and funding, the federal government is increasingly recognizing this important work. In December, the Biden administration signed an agreement with the Nez Perce Tribe, CTUIR, Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, and Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation that will bring approximately $1 billion into the Northwest for projects related to salmon recovery in the Columbia River. The deal marks a major change in how salmon projects are run: Going forward, tribes and states—instead of the federal hydropower agency, Bonneville Power Administration—will control how that money is spent. Through the Inflation Reduction Act, tribes can also apply for billions of dollars in funding that’s available for climate-change incentives, such as clean energy tax credits, drought relief, and ecosystem protection.

Attendees of the 2023 Tribal Climate Camp—where delegations from nearly two dozen tribes shared knowledge on climate adaptation strategies—view young salmon at the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe's fish hatchery near Port Angeles, Washington.

AP Photo/Lindsey Wasson

Sharing ideas—and power

The federal government is encouraging tribes to take the lead in climate change planning, says Cris Stainbrook, a member of the Oglala Lakota and the president of the Indian Land Tenure Foundation, which helps Indigenous groups recover and manage traditional lands. In fact, some federal funding for projects is contingent on climate-change planning by tribes, and Stainbrook says the Bureau of Indian Affairs has steadily granted them more autonomy in creating those plans. “Over the last 30 years,” he says, “you've seen this progression, and the tribes have developed the technical and political acumen that allows them to do that.”

Oftentimes, tribes have had to overcome systemic racism to achieve such gains, as pointed out in the Fifth National Climate Assessment released last year. The report, used to guide federal decision-making, notes “Indigenous self-determination has been limited by institutions and policies, colonial in their organizational structure, that enable federal, state, and local governments, and private industry to make decisions for Indigenous Peoples and to maintain low levels of funding and administrative support.”

Hopi tribal member Michael Kotutwa Johnson, a specialist with the University of Arizona’s Indigenous Resilience Center, helped draft the assessment’s chapter on Indigenous Peoples. In light of climate change, he says, the assessment highlights the importance of tribal sovereignty, the power that tribes hold “to make their own decisions in the best interest of their people.”

As head of the climate change task force for the National Congress of American Indians, Leonard Forsman, who is also chairman of Washington State’s Suquamish Tribe, has likewise seen a growing appreciation of tribal land stewardship among government agencies. “They’re saying, ‘Yeah, you know, the tribes got it right. The tribes have been here forever. They know how to live with this land, and we need to do the same.’”

Below is a small sample of how Indigenous groups in the Northwest and beyond have been applying their traditional ecological knowledge in the fight against climate change.

Yakama

The Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation has been conducting large riverscaping projects along the Yakima River in southern Washington State. The effort includes returning logs and other large pieces of woody debris to the reservation’s waterways and floodplains. The physical structure of the debris, which has been absent due to deforestation and other management practices, helps keep wetland-nourishing streams from eroding into deep, narrow channels. Its presence can also create slow-moving pools of water, which are prime habitat for juvenile salmon. Aiding these efforts are the dam-building skills of beavers, a keystone species and a revered creature in Yakama legend. The tribe has been rescuing “problem beavers” from farms and urban areas, where they are often unwelcome, and re-establishing them along waterways, where they would be an ecological and climate-resilient boon.

Karuk

In collaboration with environmental groups, government agencies, and the University of Oregon, the Karuk tribe of northern California is implementing its tradition of prescribed burns. Such controlled fires, conducted cyclically, help decrease the size and intensity of future wildfires by reducing the amount of dead, woody fuel in an area and by naturally fortifying the fire resilience of its vegetation.

On the Flathead Reservation in Montana, Mike Durglo Jr., program manager for the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes Preservation Office, greets what remains of a 2,000-year-old whitebark pine tree he named Illawia, which means “great-great-grandparent.”

Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

Salish and Kootenai

As part of their Climate Change Strategic Plan, Montana’s Confederated Salish & Kootenai Tribes have begun gathering seedlings of the culturally and ecologically important white bark pine, a species in steep decline over the past half century due to climate change. Warmer temperatures have allowed the mountain pine beetle and an invasive fungus called blister rust to thrive in high-altitude areas that were once too cold to support such infestations. In their efforts to save the usually long-lived tree, tribal members have been seeking out seeds from white bark pines that have proven resistant to these scourges, and then planting them throughout the forest. The tribes are also working to emphasize the seeds as a food source that has nourished their people for thousands of years.

Alaska Native Peoples

Indigenous communities, such as the Yakutat Tlingit Tribe, and the Central Council of Tlingit & Haida, are partnering with state and federal agencies to monitor for harmful algal blooms. The blooms, which are associated with rising water temperatures, can result in toxins accumulating in shellfish species, causing potentially fatal threats to the wildlife and humans that eat them. Following a 2013 outbreak of paralytic shellfish poisoning, local Indigenous groups formed a network called Southeast Alaska Tribal Ocean Research to help safeguard their subsistence shellfisheries. With technical assistance from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, they comb beaches for signs of outbreaks, identify and assess current phytoplankton populations, and test water and shellfish samples in order to protect their people while maintaining access to an important traditional food source.

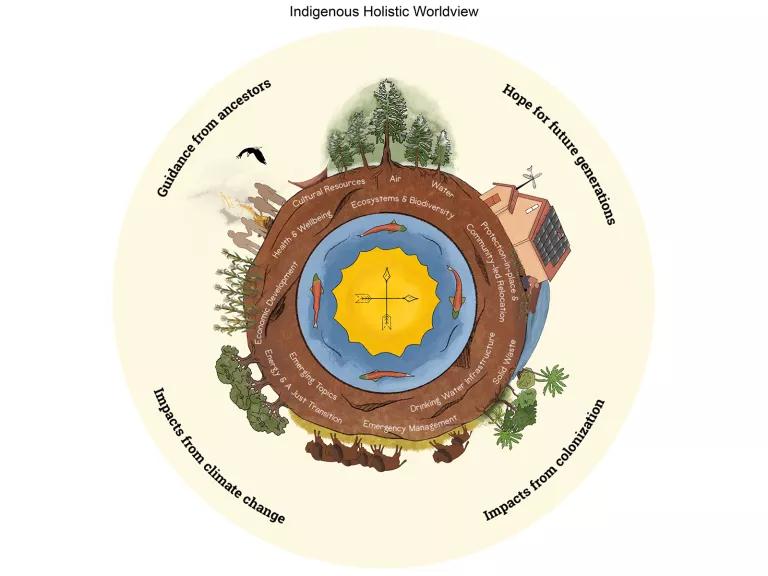

The Indigenous Holistic Worldview Illustration depicts the interconnected way in which many Indigenous Peoples experience the world. This illustration resembles a turtle in reference to creation stories about Turtle Island, which can be thought of as either the continent of North America or as the entire earth, depending on the storyteller.

Tulalip

Since 2015, Washington’s Tulalip Tribe has been conducting climate change adaptation planning that emphasizes food self-sufficiency, including salmon recovery. To reduce agricultural runoff into rivers, the tribe works with dairy farmers to recycle the manure from their cows into a nutrient-rich effluent that irrigates the farms’ feed crops. (The farmers can then sell the methane produced by the decomposing manure to the local public utility as biogas.) “For the farmer, it was just a more effective way of using the nutrients he already had” in the manure to help feed their livestock, says tribal member Daryl Williams, a longtime leader in the Tulalip Tribes Natural Resources department who now works as a consultant.

Cree

Climate change also affects Indigenous-government relationships in Canada, where Quebec provincial officials have turned to the Cree Nation for help in conserving carbon-storing boreal forests that are at risk from massive logging. For instance, Quebec nearly doubled the amount of protected lands in the Cree’s traditional territories in 2020, and with broad community input, the First Nation created a climate plan that prioritizes conservation and ecotourism over development, logging, and mining. “We wanted to come up with common visions and goals for protected areas; how we want to manage them to serve our needs based on food preservation [and] the protection of our culture, language, and wildlife,” says Chantal Tetreault, Cree protected areas manager. “It’s not just about protecting an ecosystem. It’s really about how we see ourselves in that ecosystem.”

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

Biodiversity 101

For Thousands of Years, Indigenous Tribes Have Been Planting for the Future

When Customers and Investors Demand Corporate Sustainability