Biomass 101

It turns out this controversial renewable hardly lives up to its carbon-cutting reputation.

A clearcut forest in North Carolina

© Bob Anderson/Getty

With the threat of climate change looming, developing clean, renewable sources of energy has become one of the most critical tasks of the century. Burning wood biomass to produce electricity is an increasingly buzzed-about solution—but it’s not as simple as it seems. Proponents of this energy source, often affiliated with the logging and paper industries, claim biomass is a carbon-neutral replacement for dirty fossil fuels. But many environmentalists are poking holes in that argument, demonstrating that biomass may actually make climate change worse. Here’s everything you need to know about this controversial alternative fuel.

What is biomass?

Biomass is simply any living (or recently living) organic matter that’s used for fuel. Its sources vary widely: trees, agricultural crops like corn and sugarcane, algae, and even landfill waste. It can be transformed into nearly as many different forms of bioenergy, including electricity and vehicle fuel. In all cases, it converts energy from the sun that plants have stored via photosynthesis into energy we can use.

When people discuss the biomass industry today, they are most often referring specifically to wood biomass, which makes up 43 percent of total bioenergy in the United States (second only to vehicle biofuels). All the information here refers to wood biomass.

The history of wood biomass

Our species’ development has been inextricably linked with wood biomass ever since humans first built a fire. In fact, for hundreds of thousands of years, wood was our primary form of fuel, used to heat our homes and cook our food. And it’s easy to see why its use persisted here in America: This country was rural and densely forested for much of its history, making wood widely accessible and inexpensive. It remained our top source of energy until the mid- to late 1800s, when it was replaced by a booming new industry: fossil fuels.

Loggers hauling lumber in Michigan, circa 1890

Fossil fuels (namely, coal, oil, and gas) now fulfill 79 percent of our total energy needs in the United States. We dig and drill for them deep underground, then they’re handled in a variety of ways, like being burned as coal in power plants, refined into jet fuel, or transported through pipelines.

Our heavy reliance on fossil fuels is taking a serious toll on the planet, most saliently by triggering the cascading effects of global warming. Most countries now realize that lowering the carbon emissions released when we burn fossil fuels is the key to avoiding the most catastrophic impacts of climate change.

And so, there is a biomass resurgence. Countries are turning back to wood to decrease their dependence on fossil fuels and help meet ambitious emissions-reduction targets. Regions like the southeastern United States—currently the world’s largest exporter of wood pellets for use as fuel in power plants—have ramped up production in the past decade to meet increased demand. In 2017, southern U.S. ports saw a 70 percent increase in wood pellet exports. The biggest importer is the European Union (E.U.), which treats biomass as carbon-neutral, on par with other genuine renewable energy sources like solar and wind. Some E.U. member states are now subsidizing the efforts of energy companies to boost their generation of biomass power. In light of these developments, the debate over its potential environmental impact has grown more critical than ever.

First, it’s harvested. Or, in plainer terms: Trees are cut down. Sometimes wood used as biomass is waste from other industries, like sawdust from a sawmill or unusable tree limbs from logging. But increasingly, biomass sourced for wood pellets and exported to European power plants is coming from forests that have been clearcut. This sourcing carries an enormous environmental impact with significant implications for overall carbon emissions. In addition to destroying some of the earth’s most precious ecosystems, deforestation and forest degradation together are the second-largest source of global carbon emissions, after the burning of fossil fuels.

Next, the wood is taken to a processing factory that transforms it into more efficient (and transportable) pellets or chips. From there, the wood is moved to the power plant that will combust it to generate electricity. Often, this is the longest (and most costly) leg of the journey, as in the case of U.S. biomass routinely sent to Europe on dirty diesel-powered cargo ships.

At the biomass plant, wood is fed into a combustion chamber, producing hot gas that spins a turbine and powers a generator. The final result? Electricity. These power plants are very similar in design to those that burn fossil fuels like coal—so similar, in fact, that power plants sometimes co-fire coal and biomass at the same time.

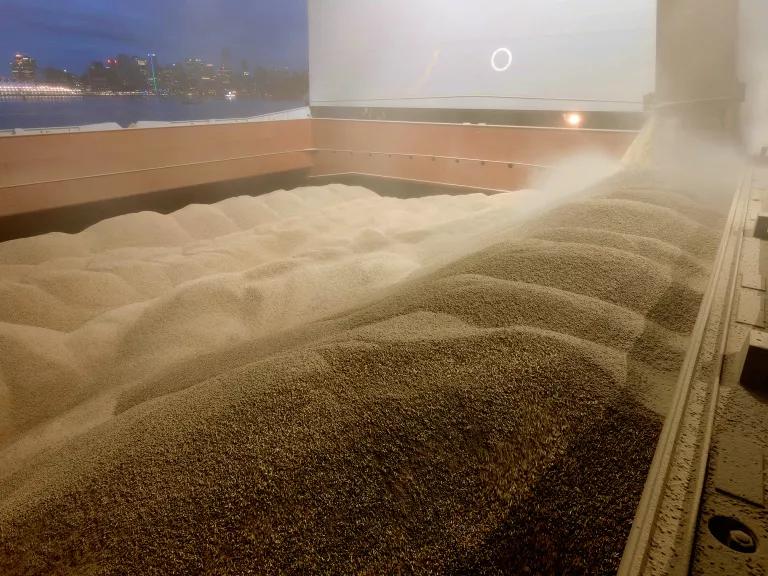

Wood pellets loaded onto a ship in Canada

Cavan/Alamy

What are the disadvantages of biomass?

It creates a huge excess of carbon in the atmosphere.

This is the big hole in the claim that biomass is a clean energy solution. Because wood is a less energy-dense fuel, biomass-burning plants emit more carbon dioxide (CO2) from their smokestacks than coal to generate the same amount of electricity. And a study commissioned by NRDC looked into the long-term emissions of burning wood pellets for large-scale electricity generation when they’re made from varying percentages of whole trees. The study concluded that even when whole trees make up only a small percentage of a wood pellet mixture, it still takes five decades for forest regrowth to lower net carbon emissions below that of coal—which forests do by capturing and storing atmospheric carbon, a process known as sequestering. (Coal is not a boon to the environment either. It’s one of the leading drivers of climate change and releases toxins like mercury and sulfur dioxide into the air.) When whole trees make up at least 40 percent of the pellets, they actually emit more carbon than coal over the course of 35 to 100 years.

We can’t guarantee the forests will be regrown.

While the logging industry may promise to sequester carbon by regrowing trees, it’s not guaranteed that they will follow through. Development plans may change. Funding may run out. Or, as ecosystems shift with the climate, nature may not cooperate. Even if trees are immediately replanted—the best-case scenario—new trees will not be able to recapture the carbon that’s been released into the atmosphere within any meaningful time frame for addressing climate change. Meanwhile, the risk of these areas being converted from natural forests to plantations is significant.

It destroys healthy ecosystems.

Even when forests are regrown, they are often replanted as a single species of tree, depleting critical habitat biodiversity. The forest degradation that results from logging for bioenergy also decreases the landscape’s integrity: Soil, the backbone of forest health, easily erodes, and its nutrients can become depleted. This is a problem not just for the forest’s health but for our health too. Healthy soil improves water quality by acting as a natural filter, keeping pollutants out of local groundwater. It also protects against flooding when extreme storms hit by acting as a sponge.

Climate action calls for planting more trees. Not burning them.

In the race to beat climate change, forests are a potent tool for reducing net emissions by sequestering carbon, in both the trees and the soil. The 2022 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report underscores this point by including land restoration as a key mitigation tool. Tearing down forests is a move in the wrong direction.

The future of biomass

Wood biomass, especially when it’s supported by government subsidies, detracts from real clean energy solutions like solar, wind, and geothermal. These renewables offer immediate carbon reductions—no decades of waiting required—and they do so without threatening the health of sensitive ecosystems or the wildlife that depends on them. Even better: Technology for solar and wind is rapidly advancing, meaning these alternative energy sources are readily available, reliable, affordable, and expanding rapidly. This is where the future of clean energy is headed.

It’s time for countries that rely heavily on burning biomass for electricity, like the United Kingdom, to stop subsidizing this dirty energy source. It’s also critical that policymakers around the world, including in the United States, avoid making the same mistakes as the U.K. and others. Burning biomass for electricity is not a climate solution, and climate and energy policies must reflect this reality.

This story was originally published on May 29, 2019, and has been updated with new information and links.

Logging remains an on-going threat to our country’s old-growth forests.

Tell the Biden administration to create strong, lasting regulatory protections for mature trees on federal lands.

Fight climate change, save America’s mature forests!

Forests—especially America's mature and old-growth forests—are natural climate solutions. But those on federal lands are threatened by ongoing logging, which means much of their stored carbon is rapidly released. Urge President Biden to create strong, lasting regulatory protections for mature forests.

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

Why Forest Carbon Offsets Aren’t a Substitute for Slashing Emissions

When Customers and Investors Demand Corporate Sustainability

What Are the Causes of Climate Change?

Why Forest Carbon Offsets Aren’t a Substitute for Slashing Emissions

When Customers and Investors Demand Corporate Sustainability

What Are the Causes of Climate Change?

Why Forest Carbon Offsets Aren’t a Substitute for Slashing Emissions

When Customers and Investors Demand Corporate Sustainability

What Are the Causes of Climate Change?

Why Forest Carbon Offsets Aren’t a Substitute for Slashing Emissions

When Customers and Investors Demand Corporate Sustainability