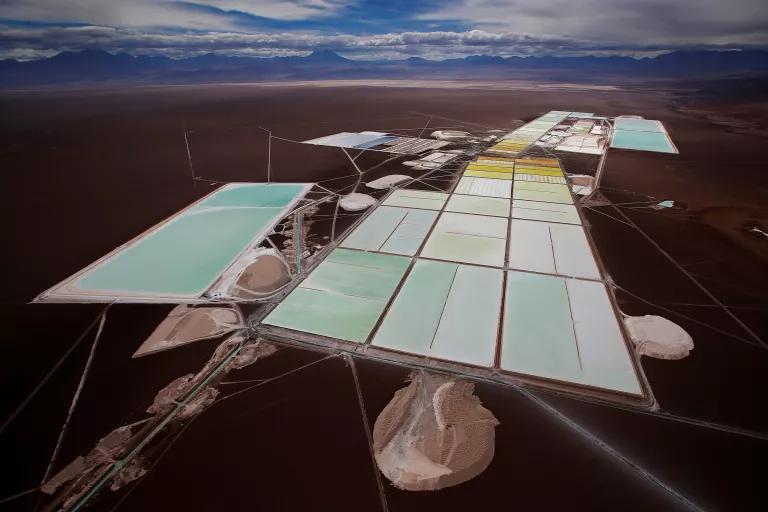

Salt flat in the Atacama Desert at the Sociedad Química y Minera de Chile lithium plant

Courtesy of Cristóbal Olivares

Elena Rivera Cardoso doesn’t mince words: “Chile is going through a tremendous water crisis.”

Rivera, the president of the Indigenous Colla community of the Copiapó commune in northern Chile, and her daughter, Lesley Muñoz Rivera, know that if the waterways in their Andean homelands continue to dry up, so, too, will their ancient culture and traditions. At the heart of the crisis is lithium mining.

Chile is the second-largest producer of lithium, a critical component of the batteries that power electric vehicles, smart devices, renewable power plants, and other technologies helping the world transition away from fossil fuels. The metal can be extracted in three ways: from hard rock, which is common in Australia; from sedimentary rock, a process currently under development in the U.S. Southwest; and through the evaporation of brines found beneath salt flats on South America’s Atacama Plateau. The latter method is by far the most water-intensive. Miners pump salty lithium-containing water, called brine, into massive ponds, where it can take years for the evaporation process to separate the lithium. The technique drains already scarce water resources, damages wetlands, and harms communities.

“This method of brine evaporation is egregious, and it's senseless,” says James J.A. Blair, assistant professor at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona and a coauthor of a new NRDC report on lithium mining in South America. “Communities are suffering a slow violence that’s creating conditions of ecological exhaustion.”

A legacy of the Pinochet era in Chile is the privatization of minerals and water, which gives companies ownership of those resources in an area. While mining operations squeeze this already dry region even drier, communities lose their access to potable water, leaving them relying on tankers to deliver it.

“We used to have a river before that now doesn’t exist. There isn’t a drop of water,” says Rivera. “And not only here in Copiapó but in all of Chile, there are rivers and lakes that have disappeared—all because a company has a lot more right to water than we do as human beings or citizens of Chile.”

An aerial view of the brine pools and processing areas of the Rockwood lithium plant on the Atacama Desert salt flat, the largest lithium deposit currently in production, in northern Chile, 2013

Ivan Alvarado/Reuters

Empty water containers outside the mud house of a park ranger at Cejar Lagoon on the Atacama salt flat, 2018

Ivan Alvarado/Reuters

The desert surrounding Copiapó, the capital of Chile’s Atacama Region, is no stranger to mineral extraction. (Indeed, the accident that trapped 33 miners for 69 days in 2010, grabbing the world’s attention, occurred in Copiapó province.) Gold, copper, boron, and other mines abound, producing toxic tailings ponds while simultaneously polluting and depleting water resources. To date, the majority of Chile’s lithium extraction has taken place on the Atacama desert salt flat, close to the country’s borders with Argentina and Bolivia, but its resources are dwindling. As global demand for lithium continues to skyrocket, mining companies are now eager to exploit the much smaller Maricunga salt flat, which lies about 100 miles northeast of Copiapó. Rivera and Muñoz, together with fellow members of the Observatorio Plurinacional de Salares Andinos (OPSAL) network, are determined to stop it.

Rivera has heard warnings from residents of San Pedro de Atacama, including the Indigenous Lickan Antay community, about mining depleting their water supplies and affecting farming and pastoral practices. “This is what has happened here, and this is what could happen to you,” Rivera recalls them saying. The Colla community’s ancient culture and traditions are also at risk. Guided by the earth mother goddess Pachamama, the nomadic group coexists with the mountains, the water, and the wildlife, and performs seasonal ceremonies in reverence to her. About 70 percent of the community now lives in the urban center of Copiapó, and if the salt flat continues to dry up, Rivera fears those who have remained in the mountains will be forced to leave.

Muñoz, who is currently studying law at the University of Atacama in Copiapó, also laments the fact that Chile’s Indigenous communities are suffering the impacts of lithium mining while seeing none of the metal’s benefits. “Nothing stays in Chile; it all goes to other places. We don’t have electric vehicles in Chile. We suffer from the contamination, and the green energy goes to the Global North. But at whose cost?”

Flamingos at Laguna Chaxa in northern Chile

Courtesy of James J. A. Blair

For now, the people living around the Maricunga salt flat have been able to keep lithium mining at bay, despite at least a half dozen mining companies currently exploring the area. Last year, the government approved a project, Minera Salar Blanco, but thanks to activists, the decision is currently going through an appeals process, which has delayed the start of any mining. Rivera asserts that the companies behind the project violated her community’s rights by failing to obtain “free, prior, and informed consent,” as established by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (which was adopted by 144 countries, including Chile, in 2007), to operate on their ancestral land.

The ecological impacts of lithium mining on the Atacama are also dire. Around 80 percent of the salt flats’ animal species are native, and the region is critical for migratory birds. In Nevado Tres Cruces, Laguna de Santa Rosa, a Ramsar Wetland of International Importance, is home to three iconic flamingo species, whose populations are in decline. Of the 53 animal species living on the wetland, 17 are considered endangered in Chile, including the vicuña, the guanaco, and the short-tailed chinchilla.

Blair and his coauthors see an urgent need to shift current practices on the Atacama Plateau. As lithium prices drop, and demand for clean energy technology continues to soar—particularly in places like in the United States, Europe, and China—experts in Chile estimate a sixfold increase in global demand for lithium carbonate between 2019 and 2030, nearly 80 percent of it for electric vehicles. (This will include emerging electric car markets such as Chile’s.) Likening brine evaporation to the deeply flawed and outdated practices of the coal industry, Blair says he would like to see a complete moratorium on this lithium extraction technique. At the same time, recognizing the urgent need for clean tech, the report proposes investing in alternative ways to meet lithium needs, such as making lithium-ion batteries longer-lasting and recycling the metal in used batteries.

Machi Elisa Loncon (center), a spiritual leader from the Mapuche Indigenous community, after being elected president of the Constitutional Assembly in 2021

Esteban Felix/AP Images

Meanwhile, Chile is in the midst of rewriting its constitution, a process launched after nationwide social upheaval in 2019. The new document, currently being drafted by 155 elected constituents, could radically reshape the country’s extractive industries—with potential benefits for the Colla community and the delicate ecosystem it calls home.

Dr. Cristina Dorador, a microbiologist with more than a dozen years studying the salt flats and one of Chile’s leading scientists, is among the Constitutional Convention members hoping to usher Chile into a more ecologically mindful future. She is also looking beyond saving her home country. Research has shown that the salt flats—landscapes that have rightfully garnered comparisons to Mars—are diverse, delicate ecosystems teeming with microorganisms that could potentially help other regions adapt to climate change.

“In the Atacama desert, we already live in future scenarios for Earth. It’s very dry, with low precipitation and extreme conditions,” Dorador says. “Organisms living here are already well adapted. We can learn a lot about our future Earth from them.” Those tiny life-forms in the desert might very well help us navigate our accelerating climate crisis, or fight future (or even current) pandemics by forming the foundation for new medicines. “But the only way to protect those microorganisms is to protect their habitats. Even if you don't see life, life is there and has to be protected.”

Rivera and Muñoz certainly see the value in fighting for the Maricunga salt flat. “Water moves everything in life,” Muñoz says. “If we don't have water to make a life in the mountains, we're going to be just another one of the many Indigenous cultures in Chile that have been exterminated.”

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

This Is How We Stand Up to Trump

Can the Great Lakes Become Fishable, Drinkable, and Swimmable Again?

Controversial New Pipelines May Slice Through the Southeast

This Is How We Stand Up to Trump

Can the Great Lakes Become Fishable, Drinkable, and Swimmable Again?

Controversial New Pipelines May Slice Through the Southeast

This Is How We Stand Up to Trump

Can the Great Lakes Become Fishable, Drinkable, and Swimmable Again?

Controversial New Pipelines May Slice Through the Southeast

This Is How We Stand Up to Trump

Can the Great Lakes Become Fishable, Drinkable, and Swimmable Again?