Katrina, Climate, and Justice: A Future in Foreshadow?

After Hurricane Laura hit Louisiana just days before the Katrina remembrance, photojournalism from 15 years ago reminds us that disaster preparation isn’t just about wind and water.

A flooded home in Lakeview, a mostly white neighborhood on the north side of New Orleans. The FEMA “X” spray-painted on homes denoted when the house was checked by rescue workers, whether it was entered, and if any hazards or bodies were found.

Fifteen years ago, the most expensive natural disaster in U.S. history struck Louisiana and Mississippi with winds at up to 130 miles per hour and storm surges of 10 to 20 feet.

Hurricane Katrina, a Category 5 storm at its peak intensity, caused an estimated $160 billion in damage and displaced more than a million Gulf Coast residents. The unusually large hurricane was also among the country’s deadliest, killing an estimated 1,833 people across seven states, from Florida to Ohio. But it was the devastation experienced in New Orleans that shocked the nation and continues to haunt the city.

Surrounded by toxic floodwaters and without electricity or Internet, the people in New Orleans were completely cut off, some literally by gunpoint. Many of the earliest accounts about New Orleans post-Katrina were inaccurate and, at worst, racially motivated rumors. But in a time before smartphones, most of the images taken during the Katrina disaster came from journalists, who brought the details and the urgency of what was happening in and around the city to the rest of the world. Their photography and footage attempted to show the scope of the storm’s widespread destruction, which spared no New Orleanian—but also revealed which residents took the brunt of the disaster, along with its seemingly never-ending aftermath. They help tell the stories of those whose lives had been the most profoundly lost or upended—low-income residents, older people, and people of color—and remind us of how much more needs to be done, structurally, politically, and socially, to protect people in a rapidly warming world.

Water rushes over a levee and into surrounding neighborhoods near Lake Pontchartrain in this shot taken from a helicopter by photographer Vincent Laforet. After the hurricane had passed through New Orleans on August 29, 2005, the failure of the levee system, poorly constructed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, led to most of the city’s destruction and deaths. By the next day, about 80 percent of New Orleans was underwater. The floodwaters didn’t clear the city until well into October.

Katrina was a Category 3 hurricane when it made landfall in Louisiana, but just the day before, it was the strongest hurricane ever recorded in the Gulf of Mexico. It didn’t hold that record long. About three weeks later, Hurricane Rita surpassed it before blowing into many of the same coastal communities hit by Katrina. A month after that, Hurricane Wilma broke the record yet again. While scientists can’t definitively link the strength of any individual storm to climate change, research confirms the trend that warming waters are leading to more frequent and more intense hurricanes. Earlier this week, two storms were simultaneously churning in the Gulf for the first time in recorded history. On Wednesday night, one of them, Hurricane Laura, slammed into western Louisiana as a Category 4 storm.

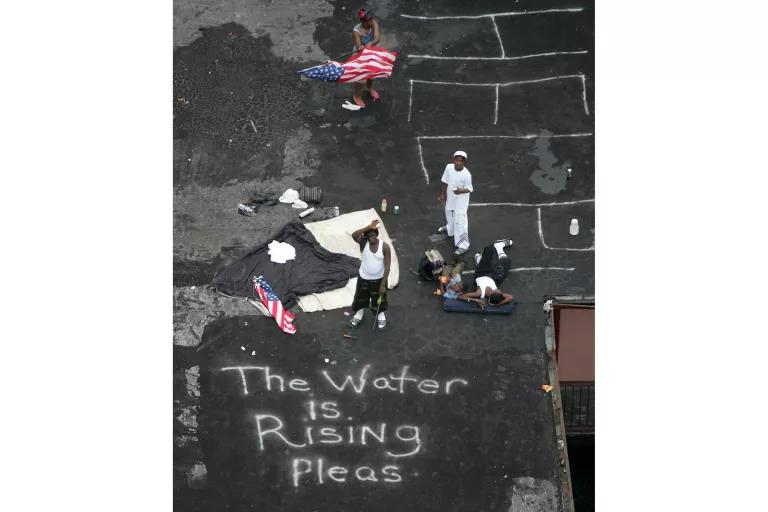

As images of the stranded came pouring onto television and computer screens across the country, a common refrain from broadcasters and viewers was, “Is this America?” This photograph, by Smiley N. Pool, both underscores and answers that sentiment. Yes, this was happening in the country America built. And like these individuals waving American flags on a rooftop, hoping to be rescued, the people populating so many of those harrowing images were disproportionately Black. “The wind isn’t racist, and the rain doesn’t target the poor,” wrote Andy Horrowitz, author of Katrina: A History, 1915-2015, in a New York Times op-ed. “But when hurricanes strike and cities flood, people who were already disadvantaged tend to suffer the most. That’s because the wind and rain alone do not define the shape of our modern disasters.”

What do shape such imbalanced outcomes are the structurally racist systems underlying U.S. society and the policies that sustain them. Redlining and investment practices that promote racial and economic segregation continue to influence who lives where and for how long. In a city built largely below sea level, it is no coincidence that New Orleans’s more affluent areas tend to be on higher ground, and while white residents lost family members, spent days on their roofs, and suffered greatly in the floods too, they were able to return and rebuild much faster.

Pool—along with Irwin Thompson and Michael Ainsworth, fellow photographers from the Dallas Morning News—won a Pulitzer Prize for their work during Katrina. “Being recognized for capturing people’s grief and pain and sorrow, it leaves you with doubts and scars,” Pool told Newsweek in 2015. “I’m a witness for these things, but I didn’t live these things.”

After Danielle Boykins-Clark, her husband, Stanley, and their children evacuated from east New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina, they took shelter on the western side of the state. Then Hurricane Rita hit in mid-September, forcing the family to evacuate again, this time farther north.

Boykins-Clark told photographer Andrew Stern, “We’ve lost everything but our faith in God” and that they were “still in shock, trying to maintain sanity.” Stern captured this image above of Boykins-Clark and her daughter resting in the Rapides Parish Coliseum Red Cross Shelter in Alexandria, Louisiana—a shelter that is now preparing to protect people fleeing from Hurricane Laura while simultaneously trying to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

The Katrina disaster led to the largest—and fastest—mass migration in modern U.S. history, described at the time by Peter Grier of the Christian Science Monitor, “as if the entire Dust Bowl migration occurred in 14 days, or the dislocations caused by the Civil War took place on fast-forward.” Photojournalist Eliot Kamenitz, a New Orleanian whose home flooded, gives a glimpse into the emotional stress and logistical chaos that occurs with the rapid displacement of so many people. His photograph above, taken nearly a week after Katrina came ashore, shows hundreds of people gathered by Interstate 10 to board buses while several pets, which weren’t allowed to join them, ran loose in the field beyond and helicopters flew overhead transporting the most ill residents and older people. (The storm subsequently inspired pet evacuation legislation to correct the failures that seperated many animals from their families, in the hopes that it would help save human lives too.) The city’s shelters, including the Superdome and Convention Center, were quickly overrun with tens of thousands of exhausted people needing food, bathrooms, and potable water.

In the weeks, months, and years that followed, the displaced people of New Orleans faced continuous obstacles to finding safe temporary housing, returning to their own homes, and rebuilding their communities. For instance, the federal government’s notoriously toxic FEMA trailers and Louisiana’s Road Home Program, which based many of its rebuilding payouts on a home’s pre-Katrina market value. This often led to homeowners in low-income neighborhoods receiving much less funding for the same types of repairs than those who lived in areas deemed more valuable. As a 2008 Mother Jones article reported, the lack of adequate infrastructure, such as open schools, public transportation, and affordable housing, also hindered people’s ability to go back home or find a new one in the years following Katrina.

After opening in 1938, the Circle Food Store became the longest-running Black-owned business in New Orleans. The supermarket was once a part of a bustling Black-owned business district, but when Interstate 10 was constructed above Claiborne Avenue in the 1960s, the character of the neighborhood changed: Black businesses and homes were torn down, starting the gentrification process, and the Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, and Seventh Wards were cut off from Treme.

As shown in this photograph by Dave Martin, the historic market flooded during Katrina and needed renovations costing millions. In 2008, Khalil Shahyd, who grew up in the Seventh Ward and is now NRDC’s senior policy advocate for the Energy Efficiency for All project, began working with the owner, Dwayne Boudreaux, to try to reopen the Circle Food Store, which eventually happened in 2014.

“It was more than a store,” Shahyd says. “In addition to often having ingredients that were more common in Black New Orleans dishes, like fresh okra, which weren’t found in white-owned stores, the Circle Food Store also had space for local dentists’ and doctors’ offices, sold small household appliances and school uniforms, and provided other services the community needed.”

Running an independent grocery store at a profit was difficult, however, and financial stresses piled up. A series of smaller floods, due to issues with the city’s drainage infrastructure, also damaged the store’s refrigeration systems, forcing it to shut down for months at a time. The Circle Food Store closed for good in 2018. It was the last remaining Black-owned grocery in the New Orleans metro area. Purchased at a foreclosure auction, the building recently opened as the Circle Food Market and now has white owners.

The Katrina disaster left many of New Orleans’s cultural institutions in ruins as well—museums, galleries, and churches, along with smaller venues like social clubs and corner juke joints, mainstays of the city’s world-renowned local music scene. Many such venues, including Black-owned local bars, never recovered or were forced to shut down and are now being taken over by white ownership.

This is a photograph of Club Desire—a famous music hall in the Upper Ninth Ward where rock ‘n’ roll pioneers Fats Domino and Dave Bartholomew performed—taken by photographer Julie Dermansky nearly 10 years after the hurricane. Rather than restore the damaged building as a historic landmark or community center, the city chose to tear it down. “The city was still working so hard on recovery, but public policy should have been in place to stabilize the building for the future,” said Patricia Gay in 2015, then executive director of Preservation Resource Center of New Orleans. “The area is totally desolate, but a plan anchored by the restoration of this building could have brought revitalization to the area.”

On August 29, 2015, Gallery of the Streets, an art collective that aims “to engage everyday spaces as sites of resistance” against issues from environmental degradation to gentrification and anti-Black violence, launched “Ecohybridity: Love Song for NOLA,” a visual opera to mark Katrina’s 10th anniversary. Art director kai lumumba barrow says the project intends to explore Black geographies in respect to tragedy and community transformation: “From the slave castles to the plantations; fields to factories; refugee camps to tent cities; dormitories to cells; slums to suburbs; the corner to the boardroom—our response to displacement shapes our self-perception and affects the cultures of those around us. In this sense, we form new ecologies that are a hybridization of multiple influences and cultures. I call this elasticity ecohybridity.”

After performing alongside a repaired floodwall in the Lower Ninth Ward, shown here in a photograph by Mario Tama, the group of about 15 Black feminists dressed in white joined a second line parade crossing over the Inner Harbor Navigation Canal. As they marched, they danced around a float of a small wooden house that stated, “Housing is a human right.”

Since 2005, the federal government has spent $14.5 billion on fortifying the city’s levees and floodwalls, ones the Army Corps says could potentially withstand a 100-year storm—a claim debated by some experts who are concerned that rising sea levels will require increased storm surge protections. Maintaining updated evacuation plans for New Orleans will also be crucial, since rebuilding has occurred in many of the most-at-risk areas for flooding, against the advice of the National Research Council, which formed post-Katrina to assess what went wrong and how to prevent it from happening again.

While activism, and the emergence of groups like Women of the Storm, in support of the city’s still-recovering communities continues to grow and while many New Orleanians feel safer behind stronger and taller levees, distrust and uncertainty linger—feelings that undoubtedly intensify each time a new hurricane swirls over the Gulf.

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

What Are the Effects of Climate Change?

Mutual Aid and Disaster Justice: “We Keep Us Safe”

Honolulu Charts a Path Away from Fossil Fuels

What Are the Effects of Climate Change?

Mutual Aid and Disaster Justice: “We Keep Us Safe”

Honolulu Charts a Path Away from Fossil Fuels

What Are the Effects of Climate Change?

Mutual Aid and Disaster Justice: “We Keep Us Safe”

Honolulu Charts a Path Away from Fossil Fuels

What Are the Effects of Climate Change?

Mutual Aid and Disaster Justice: “We Keep Us Safe”