Each August 9, the United Nations observes International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples. The occasion serves to promote the rights of the estimated 370 million indigenous peoples in the world today, as well as recognize their achievements and contributions. On this day, it is important to also consider how to honor and respect these communities as they face the imminent threat of climate change.

Indigenous people lead low carbon lives and are excellent stewards of the environment. Unfortunately, the rampant carbon pollution and resource depletion caused by developed and developing countries means indigenous populations now increasingly face the dire consequences of a warming climate.

In honor of International Day of the World’s Indigenous People, here are three things you need to know about indigenous peoples and climate change:

1. Indigenous communities are already feeling the devastating effects of climate change.

For indigenous communities, climate change is not a future concern; it is a problem of yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Many of the world's indigenous people live in isolated communities and their livelihoods are contingent on nature and the weather, making them vulnerable to increasingly unstable weather patterns. Just last month, Lake Poopó in Bolivia dried up for good and the Uru-Murato people, who depended on the lake for food, jobs, and medicine, joined a growing group of climate refugees. After centuries of living off the land, many Uru people have now moved to working in nearby mineral mines, a trade they are unfamiliar with. In Brazil, the Kamayurá people of the Amazon are experiencing a decimation of local fish stocks due to decreased precipitation so severe that Kamayurá children have resorted to eating ants on their traditional flatbreads. Despite their high risk and vulnerability, rarely is the impact of climate change on indigenous groups adequately addressed in national mitigation and adaptation policies.

2. Indigenous peoples’ natural resources and rights are being exploited.

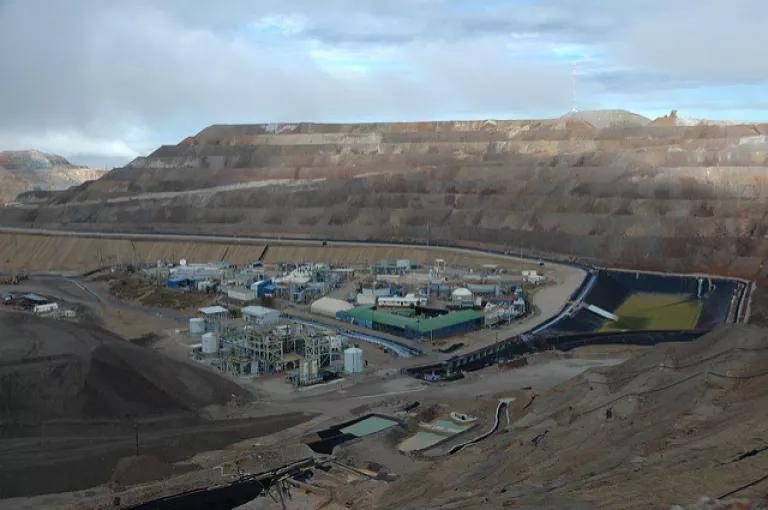

Time and time again indigenous communities find themselves up against the deep pockets, attorneys and lobbyists of corporations that undermine their land rights in exchange for access to natural resources. Mining, energy, and agricultural activities are routinely carried out on or near indigenous peoples’ lands without their free, prior and informed consent. Often, these activities lead to the irreparable degradation of communities’ land and natural resources. Maxima Acuña, a Peruvian subsistence farmer fought against the Newmont Mining Corporation’s efforts to build a US$4.8 billion open-pit gold and copper mine on her land and now faces constant death threats and harassment for her activism. In Honduras, Berta Cáceres was murdered this past March following years of threats for her role in pressuring Desarollos Energeticos, one of the world’s largest dam builders, to pull out of the Agua Zarca Dam project at the Río Gualcarque. Around the world, conditions for indigenous environmental advocates are only becoming more dangerous. In 2015 alone, 185 environmental activists, most of them fighting for indigenous rights, were killed. This represents an increase of 59 percent from 2014 and is the highest number of activist murders ever recorded.

3. Indigenous communities can be part of the solution.

Although they comprise only four percent of the world’s population, indigenous communities hold legal rights to about one eighth of the world’s forests and utilize 22 percent of land surface. In doing so, they maintain 80 percent of the planet’s biodiversity in, or adjacent to, 85 per cent of protected areas. Collectively these forests contain approximately the same amount of carbon in all of the forests in North America. Indigenous communities’ influence in preserving ecosystems and mitigating climate change through forest carbon storage is enormous and up until now, undervalued. A recent study from the World Resources Institute and Rights and Resources Initiative reveled that strengthening community forest rights is a low-cost strategy to safely store at least 37 billion tonnes of carbon globally. Improving legal protection for forest communities can enable indigenous peoples to resume their steward role within forests and act as a safeguard to rising global temperatures.

Looking Ahead

The good news is that countries and international organizations have begun to acknowledge the need for international instruments to protect these vulnerable communities and are making an effort to include members of indigenous communities in decision-making. In 1997, when countries endorsed the last major climate agreement in Kyoto, Japan, indigenous people were not even referenced in the text. A decade later, the United Nations drafted a Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in an effort to set a standard for their treatment. Now, the Paris Agreement signed earlier this year makes five explicit references to indigenous peoples, their rights, and their traditional knowledge and makes a case for the importance of their inclusion during the implementation of the treaty. While there is still work to do, this is encouraging progress.

As we move forward in the process of implementing the Paris Agreement, it is critical for leaders around the world to hold each other, corporations, and governments accountable for sticking by the promises they have made. For the Paris Agreement to truly mark a turning point for climate change, its implementation must be inclusive and equitable for all peoples, especially those groups who have historically been disproportionally affected and under-represented. And we must put people over profit every single time.

This blog was completed with the help of contributions from Ellice Ellis, Urban Alliance Intern with NRDC.