Clean Energy Standards: Why We Like Them & What to Look For

The power sector has the potential to deliver much of the solution to the climate crisis if we can clean the grid and electrify many other sources of emissions.

John Kelly/Alamy

The power sector has the potential to deliver much of the solution to the climate crisis if we can clean the grid and electrify many other sources of emissions. Over the past decade, electric utilities, with policy maker, consumer and business support, have successfully cut carbon dioxide emissions by more than 25%. With the right policies, we can accelerate these reductions, create new clean energy jobs and protect consumers from high utility costs and climate damages.

But while the power sector has been making progress, far more needs to be done to reduce fossil fuel emissions from the sector. A national clean energy standard can move us away from polluting generation by incentivizing what Americans of diverse political stripes want—more clean energy. A well-designed clean energy standard will help push out the dirtiest generation while directing greater investments in the zero-emission clean energy we all want to see.

Starting with Iowa in 1983, 29 States now have clean or renewable energy standards in place, with a growing number now accelerating requirements to achieve 100 percent clean energy. And thirteen major electric utilities have pledged to achieve 100% clean or net-zero (carbon) energy, with many more committing to exceed 80% clean energy. This is important, notable progress, but is not a substitute for federal action. Many states still lack these policies and utility commitments are neither binding nor universal. A strong federal standard will ensure that the whole nation pulls together to achieve our clean energy future and will position the U.S. to lead global efforts to tackle climate change.

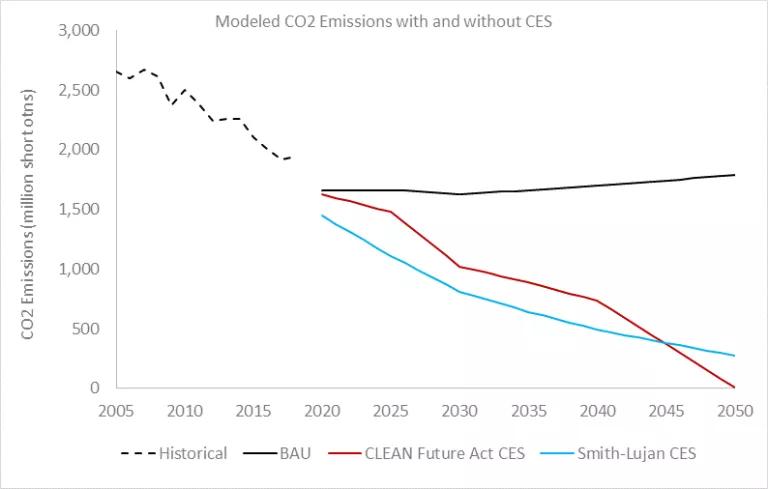

In this 116th Congress, we have already seen a clean energy standard introduced by Senator Smith and Representative Lujan, another included in the CLEAN Future Act, and a third expected this summer. The recently released Report from the Select Committee on the Climate Crisis also recommends a clean energy standard. We are encouraged by these efforts and are looking forward to working with lawmakers on these bills. The “Design Features” section below highlight key design questions and initial results from our modeling of these proposals.

The basic clean energy standard approach

There are two prominent power sector standards designed to ensure that generation transitions from polluting to clean electricity.

The first approach is to limit carbon pollution from power plants by requiring those plants to pay a carbon fee or by capping the total amount of carbon emitted. The successful Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (“RGGI”), a bipartisan effort of 10 states, is one example of a carbon cap.

The second approach is a clean energy standard that requires that utilities to increase the amount of clean energy used until it accounts for 100% of the electricity supplied. A clean energy standard does this by requiring that suppliers of electricity hold clean energy credits reflecting clean electricity generation.

Both a carbon price/cap and a clean energy standard can produce similar effects on our electricity markets. Each approach increases revenue for clean generators and decreases it for polluting power plants.

Design features of a clean energy standard

Who is regulated?

Unlike policy approaches that set standards on polluting electricity generators, clean energy standards apply to the company which delivers electricity to homes and businesses. In much of the country this is a different company from those that generate electricity.

How to structure a clean energy standard?

As noted, a clean energy standard requires that suppliers of electricity hold credits that are earned through the production of clean energy. Many state renewable and clean energy standards include a list of resources eligible for credits. This leads to complexity, debate and, in some cases, lists that reflect politics—not the most effective way to reduce emissions. A better approach is to provide full credit only for those resources that are really zero-emitting and to rate other generation based on their emissions profile (lbs of CO2/MWh). This ensures zero-emission power sources receive the largest incentive and makes sure that we push out the dirtiest generation first.

A standard that distinguishes among resources in this way means zero emitting resources run first and that gas operates before dirtier coal plants. Importantly, it does not give a windfall to gas generators; gas power plants will end up earning about the same amount for each MWh they generate because the amount that they earn from the credit market will lower the amount that they earn from the energy market. And of course, the policy phases out gas altogether as the required percentage of clean energy increases.

How does it benefit public health?

We modeled the clean energy standard included in the CLEAN Future Act and the Smith-Lujan CES with ICF’s Integrated Planning Model. Each policy could save thousands of lives. Our initial modeling of the CLEAN Future CES (we did not include the other provisions in that draft bill) showed that it would avoid approximately 3,200-7,280 premature deaths per year, compared to business as usual, due to reduced NOx and SO2 pollution from power plant operation. Our modeling of the Smith-Lujan CES indicated that approximately 3,000-6,850 premature deaths per year would be avoided on average through 2050.

How ambitious is it and does it deliver significant reductions in carbon emissions?

In order to address the climate crisis, countries like the U.S. need to reduce emissions as fast as possible and achieve economy-wide net zero GHG emissions no later than 2050. The power sector has the potential to move much faster than other sectors, particularly given the low cost of wind and solar power generation and the cost-effective opportunities to improve energy efficiency. We think provisions that accelerate the standard if costs are lower than expected can be a useful mechanism to account for the uncertainty we face.

Here’s the carbon dioxide reduction we saw when we modeled the Smith-Lujan and CLEAN CES in IPM (NRDC plans to release these model results soon):

How does it address equity concerns?

Policy makers and the environmental community need to better assess the equity impacts of market-based approaches to environmental regulation. A clean energy standard would produce large health gains by displacing polluting power plants. As noted, our initial modeling shows thousands of lives saved per year nationwide. But given the inequitable distribution of polluting facilities, we need to give far more consideration to ensuring these reductions will help the communities most harmed by fossil fuel pollution. We look forward to working with these communities to make sure that we create the right package of policies to protect the health of disproportionately burdened communities.

It is also important to protect low income customers. A clean energy standard can minimize the costs of decarbonizing the power sector which will help avoid cost increases. But we should also add complementary measures like weatherization assistance program that can help lower energy bills faced by low income customers.

What about other environmental impacts?

A clean energy standard, like a carbon fee or cap and trade program, will provide additional support to resources that have low carbon emissions but may have other impacts. It is important to keep and strengthen other safeguards to minimize their environmental and health impacts. For example, we’d like to see progress addressing nuclear waste, strong protocols for the permanent sequestration of captured carbon, and reductions in upstream methane leakage.

How does it interact with existing state programs? And can they continue to go faster or are they preempted?

A federal standard should not preempt state standards that are equally or more ambitious as the federal program.

What about the rest of the economy?

In addition to the power sector, emissions from the transportation, industrial, agricultural, and other sectors need to be addressed. A clean energy standard combined with other sector-specific policies allows Congress to address the needs and barriers of each sector.