A Champion for Equitable and Sustainable Infrastructure

Stephanie Gidigbi Jenkins is pushing for public policy solutions that address social equity and climate justice while strengthening access to reliable transportation, affordable housing, and open spaces.

Stephanie Gidigbi Jenkins, director of policy and partnerships for NRDC’s Healthy People & Thriving Communities Program, speaking at a Friends of Transit Conference in Phoenix

One of Stephanie Gidigbi Jenkins’s favorite work projects from her time at the U.S. Department of Transportation, where she served as a political appointee for the Obama administration, was the Every Place Counts Design Challenge—later known as the Every Day Counts Community Connections initiative. The federally funded initiative aimed to repair decades-old divisions created from the development of interstate highways by seeking to reconnect communities cut off from economic centers and transit hubs.

Today, Gidigbi Jenkins continues this mission of reimagining the nation’s aging—and often unjust—infrastructure at NRDC, where she serves as the director of policy and partnerships for the Healthy People & Thriving Communities program. She coordinates efforts to push for a federal plan to invest equitably and sustainably in 21st-century infrastructure and amplifies community-led solutions around housing, transportation, cultural preservation, green space, and parks through the Strong, Prosperous, and Resilient Communities Challenge (SPARCC), a partnership between NRDC, regional advocates, and community development organizations. In addition to advocating for policy solutions that address climate injustice, she also works to ensure decision makers are focused on redressing the legacy of unjust investments from our past.

How has the siting of infrastructure reinforced systemic racism and economic inequities in U.S. cities?

When we were building out much of our country’s infrastructure 60 years ago, it was a different America with different values. We divided neighborhoods based on race and class.

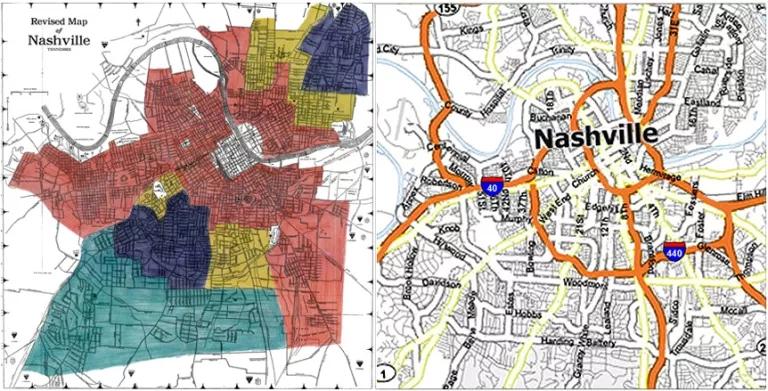

To improve our current system, we need to understand our history and look at how investments (or the lack thereof) have impacted communities. Take Philadelphia’s Chinatown, for example. When transportation officials were building out the I-676 expressway in the 1960s, they cut through the entire neighborhood, creating both an economic division and a cultural division that still exists today. Nashville’s I-40, Minneapolis’s I-94, and Spokane’s I-90 all similarly impeded residents’ mobility and access to economic opportunity.

Now, where you live plays a huge role in determining your success in life—your zip code often has more of an impact on your life than your genetic code. For economic growth, your ability to move up the ladder is directly tied to where you are physically able to get to and where you need to go. Without that access, you’re stuck. The economic and cumulative impact of harmful infrastructure projects, further exacerbated by the impact of climate change, makes matters worse for Black, brown, and Indigenous communities often relegated to neighborhoods prone to flooding, poor air quality, drinking water violations, and public health challenges.

What are the key hurdles in developing more equitable infrastructure in our communities moving forward?

When we talk about equitable development, we mean investment without displacement—in other words, making infrastructure upgrades while also thinking about the long-term impacts on nearby communities. One of the challenges with this is that we often think in silos. For example, when we push for green spaces that can address flooding or other extreme weather concerns, we may not be thinking about how that would impact affordable housing. So we end up making this big investment, but those who might benefit most from it can’t afford to stay. We need to have a holistic thinking process upfront, planning for not just who or what is coming but who is here now. The challenge isn’t that neighborhoods are getting major investments; the challenge is that we are displacing people, culture, and community assets in the process. We need to put mechanisms in place to recognize the specific needs of those who are already struggling.

Can you point to a city that is doing good work to prevent displacement while implementing new infrastructure projects?

Los Angeles is doing a lot of work to ensure communities can anchor in place. One of the groups NRDC works with, the Los Angeles Regional Open Space and Affordable Housing (LA ROSAH) Collaborative, addresses the challenges of green gentrification and displacement in the wake of large public investment projects to increase park spaces, like Measure A and Proposition 68. The group strategizes on how to support affordable housing next to new green infrastructure, prioritizing those in the community that would be impacted the most: low-income and communities of color. Developing strategies for joint affordable housing and park development allows LA ROSAH to tackle the two pressing issues together—not only do they want to elevate climate resilience and mitigation plans, but they also want to make sure that affordable housing is integrated as part of those policies. This is the type of work that pushes for equitable and sustainable development.

In addition to helping communities benefit from new developments coming to their cities, how do you help ensure they can maintain the qualities that make them unique?

The other piece of gentrification and displacement beyond the loss of people is the loss of culture. I learned years ago from a West African cultural perspective that an ancestor lives on until the last living person remembers their name—and I translate that same truth into my work, by acknowledging the cultural legacy of a community. In some places, there were neighborhoods and communities that existed long before a major investment was made, yet once the investment came, history and culture were lost.

In L.A., we see gentrification’s impacts on the cultural identity of Little Tokyo, a small Japanese-American community downtown that survived the dark period of internment during World War II. In 2016, East Coast art dealers started moving into the area, and construction cranes followed. NRDC worked to preserve the neighborhood through our Green Neighborhoods Initiative (which evolved into SPARCC). We see unique spaces like Little Tokyo as cultural assets, which can leverage greater green investments that reflect the community’s needs. Incorporating the community’s culture while bringing in modern-day development projects allows them to be seen and heard.

With COVID-19 causing major disruptions to our country’s transportation systems, how do you think the sector should change moving forward?

While there has been a significant decline in transit use and demand across the board, transportation remains a vital aspect of our economic recovery as a nation. In addition to the steps transit agencies have already taken to decrease exposure to COVID-19—like sanitizing, providing masks, and publishing real-time data on crowding—we also need to focus on transit access, reliable service, and operating hours to support the commuting workforce’s actual needs.

The transportation sector has also become the largest contributor to U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. NRDC is working on policies that will not only help “green” the sector but also benefit communities in an equitable way, including clean transportation solutions, general mobility solutions, transportation electrification and clean fuels, and opportunities for intergovernmental coordination. Something that brought me the greatest joy this summer was the House passage of HR2, the INVEST in America Act. It was a bold investment in our infrastructure across the board, with a particular focus on green housing, climate-resilient transportation, and clean water. This bill will play an essential role in shifting our investments toward infrastructure that supports low-carbon transportation options like transit, biking, and walking. It will also put funding directly in the hands of local communities. We know that low-carbon travel is more likely when communities are planned around high-capacity, high-quality transit and transit-oriented development, so those are all factors we need to strive for.

What drew you to pursue a career in infrastructure policy, and what keeps you motivated in your work?

For me, infrastructure is a powerful space to advocate because it brings all of our work together in an intentional and inclusive way. No matter what kind of neighborhood you live in, we all need a road, a home, and a community. Our work on buildings, transportation, and parks and open spaces, combined with our efforts to make sure people—especially those most in need—have access to basic necessities like clean water and affordable housing, are all connected to ensure that a community can thrive.

Sometimes when you’re advocating for different policies, you can get stuck on the technicalities and, in the process, forget about the residents and what they need. When you start to address things like investment without displacement, you bring people back to the center of the work. Much of the work I do with SPARCC and other regional partnerships helps to reground me in that way.

In 2020 we faced a renewed awakening to systemic racial injustice, economic fallout from COVID-19, and the realities of our growing climate crisis. How have these dramatic events reinforced your mission at NRDC?

If anything, they have affirmed the need to have organizations like NRDC be light bearers during this dark time. We need to continue working with local leaders and elevate community-led solutions—you can go to any neighborhood, and residents will have big, bold ideas on how to improve their community. It’s at that local level that you’re able to see the resilience of our country.

The public health crisis has magnified the disparities that have existed for decades, if not centuries. The protests and violence around the country highlight an inequitable system that Black, brown, and Indigenous communities have been required to navigate for decades. All of these changes have costs and consequences—for our economy, our public health, and our infrastructure. However, at this moment, we have an opportunity to address the issues of our past, tackle the challenges of this moment, and build a better future.

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

Sharing the Road: Safer Streets Means Safe for Everyone

What Is Congestion Pricing?

How to Stop a Highway

Sharing the Road: Safer Streets Means Safe for Everyone

What Is Congestion Pricing?

How to Stop a Highway

Sharing the Road: Safer Streets Means Safe for Everyone

What Is Congestion Pricing?

How to Stop a Highway

Sharing the Road: Safer Streets Means Safe for Everyone

What Is Congestion Pricing?