Breathing in Harm: The Toll of Freight Pollution in California

Diesel trucks, making up just 6 percent of vehicles in California, are responsible for a disproportionate amount of harmful emissions, severely impacting communities near freight routes like those in the Inland Empire.

A torn-down home in South Bloomington, California, where the proposed Bloomington Business Park was approved.

Courtesy of the People's Collective for Environmental Justice

This blog was coauthored by Melissa Rivas Hernandez, an NRDC 2024 summer intern, and Andrea Vidaurre, cofounder of the People’s Collective for Environmental Justice and a 2024 Goldman Environmental Prize Winner

Support for the internship program is provided by the U.C. Merced Division of Equity, Justice & Inclusive Excellence.

Millions of Americans are exposed to toxic air pollution daily, often unaware of the severe health consequences. This issue is particularly acute for newborns, who may develop respiratory illnesses and/or cognitive disabilities due to their mother’s exposure to toxic diesel fumes. The primary culprits behind this pollution are diesel trucks that, despite comprising only 6 percent of vehicles on the road in California, emit a disproportionate 31 percent of nitrogen oxides (NOx) and 55 percent of particulate matter pollution. This not only contributes significantly to poor air quality but also poses grave health risks, particularly to frontline communities residing near major freight routes and facilities, from the ports to California’s “Inland Empire.”

The impacts of diesel truck emissions on communities

Ports like Los Angeles and Long Beach are vital to the U.S. economy, handling a significant portion of the nation’s cargo, including electronics, chemicals, crude oil, and much more. In 2023, these ports managed more than eight million twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs).

Such high cargo volumes rely on diesel-fueled equipment and vehicles, contributing to elevated levels of NOx and particulate matter in surrounding areas. This constant exposure to toxic fumes profoundly impacts communities in neighborhoods like San Pedro, Terminal Island, Wilmington, and others, where residents endure polluted air and constant noise from freight operations.

However, the problem doesn’t end there—the cargo from seaports makes its way into a system of “dry ports” in the Inland Empire, where millions of square feet of warehouses are used to ship more than 40 percent of goods to the rest of the country. As a result, California’s Inland Empire has been burdened with high diesel vehicle activity for the “economic benefit” of the United States and is plagued with some of the worst air quality in the nation.

The Inland Empire: A “diesel death zone”

Cargo coming from the ports makes its way through railways and heavy-duty trucks and ends up at warehouses, which serve as the bases for shipping goods across the country. The carbon emissions from the ports, trucks, railyards, and more contribute to air pollution in a region that is geographically situated inland and surrounded by mountains, trapping the polluted air.

A home in the West Side of San Bernardino, California

Courtesy of the People's Collective for Environmental Justice

Communities such as Bloomington, Colton, Fontana, Rialto, and San Bernardino, which are Assembly Bill 617 environmental justice (EJ) communities, have been the ones to pay the price of warehouse expansion, often with their health, the displacement from their homes, and the erasure of communities. It is not uncommon for warehouses to be approved and placed just a few feet away from residential areas and schools, in neighborhoods where existing railyards already increase exposure to harmful emissions and worsen air quality in the region. This puts Inland Empire residents at greater risk for negative health impacts.

Some communities in the Inland Empire have been studied and labeled as “cancer clusters,” due to their overwhelming exposure to diesel emissions and poor air quality, such as in San Bernardino. Overall, the region has seen homes purchased and land next to homes repurposed to make way for warehouses, which have brought more trucks into these already burdened communities.

The human cost: A closer look at the Inland Empire

A California health report revealed that households earning around $20,000 annually face vehicle pollution rates approximately 20 percent higher than the state average. Additionally, according to a study by the Union of Concerned Scientists, Black Californians are exposed to 43 percent more particulate matter 2.5 particles and Latine Californians 39 percent more, compared to white Californians. Particulate matter produced from automobiles is also associated with several diseases. And NOx are gases often produced from the exhaust of motor vehicles or the burning of natural gas and are linked to various health problems, including premature death. Moreover, noise pollution from freight operations contributes to stress, sleep disorders, and other adverse health impacts among residents.

A more recent consequence seen in the Inland Empire, directly tied to the expansion of the logistics industry—the process of obtaining, producing, and distributing products to the right place and in the right quantities—has been the erasure and displacement of communities like Bloomington, an unincorporated community that is more than 90 percent Latine. Developers aiming to expand the industry have not only taken the land around homes in the community but have targeted a community with a rich culture and unique rural environment. Residents had access to small businesses such as nurseries and fresh food markets, as well as cultural community events and more. Over the past decade, the community went from many people riding their horses around to a dramatic increase of heavy-duty diesel trucks on roads with no sidewalks, putting children walking home from school at risk. A warehouse project planned in the area would add 9,000 truck trips to an already burdened community that also has three neighboring schools.

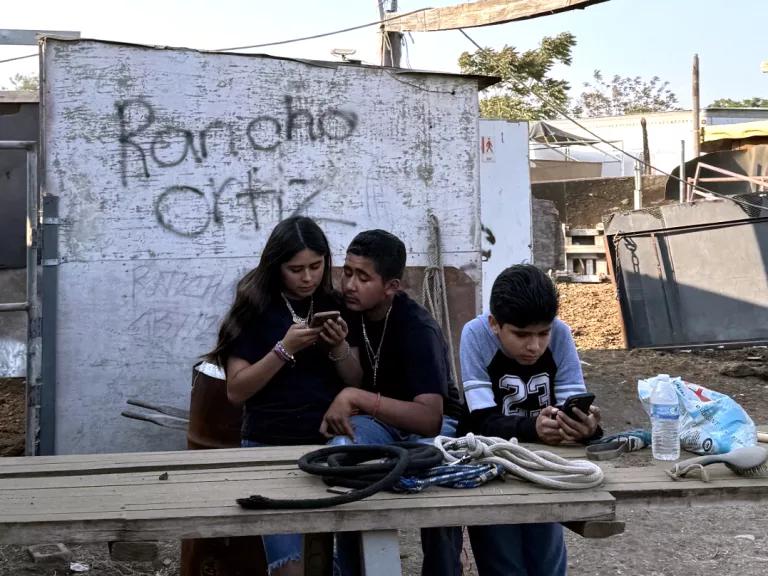

The Ortiz family at their ranch in Bloomington, California

Courtesy of the People's Collective for Environmental Justice

One particular family, the Ortizes—a family of six who have lived in Bloomington for more than 10 years and own several horses, goats, and more—are local business owners of Charritos de Bloomington. They did not wish to move and leave their home behind, but have been forced to because of a project that would increase overall exposure to emissions in the area. In the process, they have not received support to relocate and have been directly harassed by the developer. This is just one example of the many instances of communities being displaced and erased in the Inland Empire by warehouse development, which brings increased diesel exposure to those left living next to these projects.

Why communities advocate for clean truck standards

In response to these disparities, frontline communities and EJ groups have mobilized to advocate for cleaner air through policies like the Advanced Clean Trucks (ACT), Advanced Clean Fleets (ACF), and Heavy-Duty Engine and Vehicle Omnibus (HDO) standards. The ACT and ACF regulations aim to accelerate the adoption of zero-emission vehicles (ZEVs), setting zero-emission vehicle manufacturing targets as a percentage of total sales starting in model year 2027 and aiming for 100 percent of medium- and heavy-duty vehicle sales to be zero emissions by 2036. HDO requires heavy-duty trucks to reduce their NOx emissions by 90 percent by 2027. Enforcing these clean truck standards is critical to mitigating the health impacts of freight pollution and improving air quality in affected communities.

For example, the ACT rule will result in $8.9 billion in health savings from 2020 to 2040; the ACF rule is expected to bring $26.5 billion in statewide health benefits; and the HDO will help secure $36 billion in statewide health benefits.

The urgency of transitioning to zero-emission vehicles

The urgency to transition to zero-emission vehicles is clear: Communities are tired of putting their health on the line every time they step outside. Accelerating the transition to ZEVs is critical for many frontline communities, as well as port workers and truck drivers, but it’s also a win for the freight industry because charging vehicles is cheaper than using diesel gas in the long run, and there is less maintenance required.

While adoption of clean truck standards like ACT, ACF, and HDO have been established, their effective enforcement, widespread adoption, and implementation are necessary to actually reduce harmful emissions. This is why advocates mobilized on August 14, 2024, in support of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency granting California a waiver to enforce its ACF rule. Advocates and community leaders must continue to pressure policymakers to prioritize these clean truck standards, including supporting initiatives that lower the barriers to ZEV adoption, such as investments in charging infrastructure. By doing so, we can ensure that all communities benefit from cleaner air and improved public health.

A call to action

In this critical moment, we cannot afford to delay. Every day that passes without significant action perpetuates the health disparities caused by freight pollution. Let us stand together to advocate for a future where clean air is a right, not a privilege, and where every community can thrive in a sustainable environment.

By transitioning to zero-emission vehicles and supporting clean air policies, we can protect the health of our communities, saving money and our environment. The time to act is now.