Why All the Concern About Underwater Ship Noise?

Commercial shipping is the primary contributor to underwater noise pollution in the ocean.

Louis Vest via Flickr, CC BY-NC 4.0

Many of us are newly aware of the significant role that global shipping plays in transporting goods around the globe after recent supply chain disruptions caused shortages and delays in a wide range of products. Each year, between 80 - 90% of products and commodities in global trade are carried by ships. Worldwide, the international commercial fleet numbers over 100,000 ships.

It is perhaps no surprise, then, that commercial shipping is the primary contributor to underwater noise pollution in the ocean. A cargo vessel emits around 190 decibels of noise – which is louder even than a jet engine at take-off. And noise travels fast in water – four times faster than in air – meaning that noise from a ship can carry exceedingly far, impacting a broad swath of ocean as it travels.

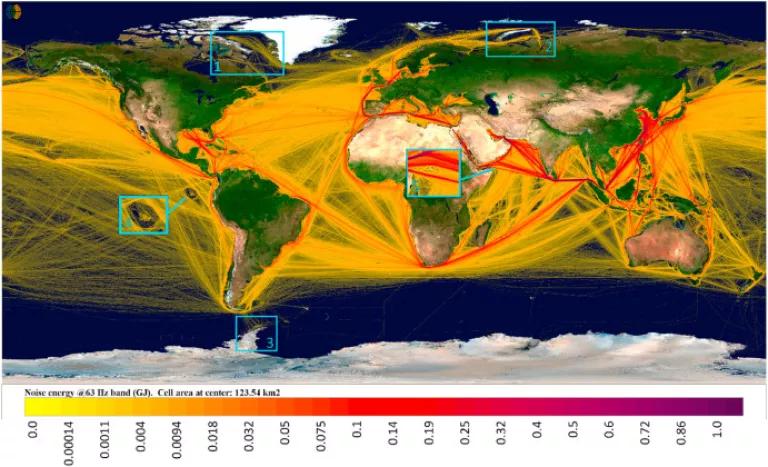

A recent study mapped the geographical distribution of global underwater noise emissions from ships in 2019, demonstrating that very few areas of the ocean are unimpacted by shipping noise (see Figure 1). And the problem is only expected to get worse.

Global map of underwater noise emissions from ships in 2019. The labeled areas are 1: Baffin Sea, 2: Kara Sea, 3: Palmer basin, 4: Galapagos Islands, and 5: Socotra.

From Jalkanen, et al (2022).*

The total carrying capacity of the global fleet nearly quadrupled between 1996 and 2020, as new and larger ships have been added to keep pace with the growing global economy, and industry analysts expect this growth trend to continue. Scientists measuring ocean noise have found that noise from shipping is doubling roughly each decade.

What are the implications of all this ship noise? Many, if not most, of marine species use sound to carry out the important, day-to-day activities necessary to survive. It is the way that marine animals, from whales to fish to lobsters, communicate with one another, find food (and avoid predators), reproduce, and even navigate. When ship noise overwhelms or “masks” these natural sounds, marine life has been observed leaving their preferred habitats or changing important behaviors, like singing to mates, foraging for food, or nursing babies. Ship noise has also been shown to cause elevated stress in marine mammals, which can lower the resilience of animals who already face challenges related to water pollution, climate change, and habitat/food loss.

Hundreds of studies have demonstrated how ship noise adversely impacts marine species: increased stress hormones in critically endangered North Atlantic right whales, affecting reproduction and immunity; reduced foraging by Southern Resident orcas, who are already facing scarce prey resources; narwhals becoming motionless, sinking and falling silent at relatively low levels of noise; poorer body condition in Atlantic cod; intense breathing rates and metabolic activity in European sea bass and eels; no or few toadfish eggs per clutch in noisy sites; increased risk of predation in shore crabs; restricted food uptake and slower growth rate in oysters; even a reduction in health of seagrass. The list goes on and on (and on), and what we know likely only scratches the surface.

Can anything be done to make ships quieter? Most of the underwater noise emitted from ships comes from propeller cavitation, which is a complex phenomenon to describe, but can be boiled down to a design issue that can cause a breakdown in water flow over the propeller blades, resulting in significant noise (and a loss in fuel efficiency). Cavitation can be addressed through design changes to the propeller, as well as the hull of the ship, or the use of new devices that are meant to smooth water flow into the propeller. In 2017, the shipping company Maersk modified several of its ships by installing efficient propellers and reconfiguring hulls, and found these improvements resulted in a 75% reduction in noise energy emitted from the ship.

Other elements of the ship, like its engine, also contributes noise. Solutions can include placing the engine on mounts, so it does not directly touch and thus transfer noise through the hull. Maintaining the ship hull and propeller to prevent buildup of aquatic organisms can reduce noise, as can avoiding the use of operating equipment that emits noise – like echosounders used to measure water depth - when it’s not needed.

Ships can also drastically cut their noise emissions through the simple act of slowing down. A general rule of thumb is that for each 1 knot in speed reduction, a ship’s noise is reduced by 1 decibel. An analysis by my colleague Russell Leaper found that slowing the global fleet by a modest 10% could reduce the total sound energy from shipping by around 40%. In a real-world example, the Vancouver-Fraser Port Authority in British Columbia asks ships to slow down to either 11 or 14.5 knots (based on ship type) as they approach the port, to reduce noise disturbance to the critically endangered Southern Resident orca population. The Port found that, with over 80% of large vessels participating in the slow down in 2022, underwater sound intensity in the area decreased by as much as 55%.

Both design and operational measures exist that can effectively quiet ships. Unfortunately, what is lacking is a policy driver to ensure ships adopt these measures. In 2014, the International Maritime Organization, the global body that regulates international shipping, adopted voluntary guidelines that describes these solutions so that shipowners and operators could make use of them. However, because this guidance is voluntary, and not required, the shipping industry has largely ignored them. Additionally, several ship classification societies have issued “Quiet Ship Notations”, or design guidance to large ships to become quieter. However, to date, only a couple of ships, probably as many as you can count on your fingers, have achieved these notations, out of thousands.

Until laws and regulations are enacted that require ships to limit their underwater noise, this solvable problem will continue unabated. NRDC and our allies are advocating, at the IMO and within our respective countries, for new regulations to reduce underwater noise from shipping. And as I've written here, we have a unique window of time over the next five years to ensure that the world's ships are designed to be both quiet and carbon-free. The time for action is now. Watch this space for updates!

*********

*Figure 1 is taken from Jukka-Pekka Jalkanen, Lasse Johansson, Mathias H. Andersson, Elisa Majamaki, and Peter Sigray, 2022. “Underwater noise emissions from ships during 2014-2020”. Environmental Pollution, 311: 119766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2022.119766. Used under Creative Commons license.