What We Got Out of COP26—and What’s Still Needed

We’ve reached the strongest global consensus yet that fossil fuels must be phased out. But as youth activists remind us, the seas are still rising.

Delegates holding the climate clock, a graphic to demonstrate how quickly the planet is approaching 1.5 degrees Celsius of global warming, on day twelve of COP26.

Ian Forsyth/Getty Images

No single gathering, no final accord, is going to end the climate crisis. As international climate talks wind down in Glasgow, though, the world is moving forward on three vital fronts, even as each reveals anew how much further we must go.

Global ambitions were raised in ways that take us closer to what’s needed to cut greenhouse gases in half over the coming decade, but not enough to put the world on track to keep warming below the critical limit of 1.5 degrees Celsius.

Developing nations’ access to finance and technology was improved, but not nearly enough to empower low-income countries to participate fully in the clean energy transition or protect vulnerable people on the frontlines of climate hazard and harm.

And accountability measures were strengthened but, amid reports that countries are fudging the numbers to lighten their carbon footprints, there’s no guarantee that we’ll turn the promises of Glasgow into the progress we need.

With seas rising, croplands turning to desert, species in collapse, and wildfires, floods, and storms raging, this is no longer a question of whether the glass is half full; we’ve got to find a way to fill the glass.

Some 120 leaders showed up in Glasgow to try, and here’s what they achieved.

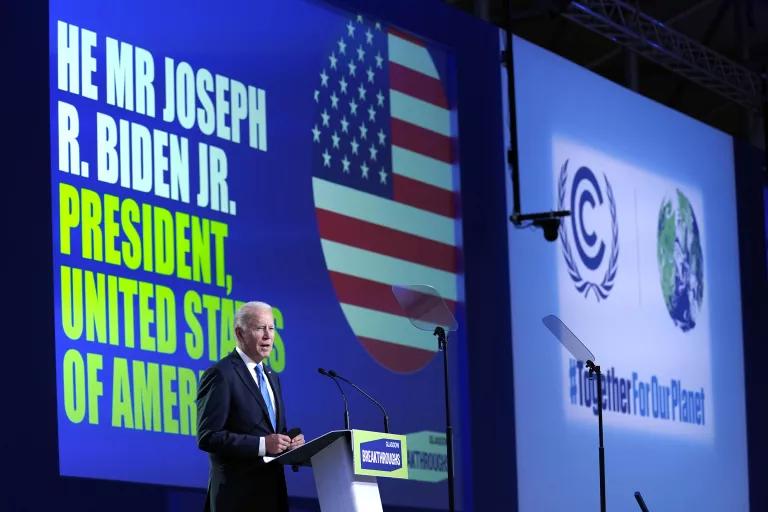

President Joe Biden defined, for the United States and the world, the stakes in the climate crisis—“the challenge of our collective lifetimes”—and the opportunity to jump-start a generation of prosperity by confronting it.

President Biden speaks during the Accelerating Clean Technology Innovation and Deployment event on November 2, 2021 Evan Vucci.

Pool via AP

He called for global cooperation based on national action, starting with his own grand strategy for driving clean energy investment to cut climate pollution at home through the Build Back Better agenda we’re counting on Congress to pass.

Perhaps most importantly, Biden re-engaged in the global climate fight, reversing four years of backsliding by his predecessor, and began the hard work of restoring U.S. climate leadership.

“We showed up,” Biden told reporters, and “we’ve had a profound impact.”

The United States and China—which together account for nearly 40 percent of the global carbon footprint—pledged to cooperate on efforts to hold global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius, or 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit, and as near as possible to 1.5 degrees Celsius, or 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit.

What’s important now is for the two countries to translate their shared commitment into the carbon cuts required to keep that 1.5 alive.

The United States joined the European Union and about 100 nations in pledging to cut emissions of methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, by 30 percent by 2030. Delivering on that goal will be key.

India committed to providing half the electricity for its 1.4 billion people from renewable sources like the wind and sun by 2030. Major nations pledged to stop financing new coal-fired power plants.

Pavagada Solar Park in Thirumani village, Karnataka, India

And Morgan Stanley, Deutsche Bank, and BlackRock joined some 450 other investment firms, banks, and insurers—with $130 trillion in combined assets—in vowing to stop adding carbon pollution to the atmosphere by 2030, and to finance projects that help countries and other companies do the same over time.

These are big commitments. Together with related Glasgow pledges, they embody the strongest global consensus yet that coal, oil, and gas are being phased out of the global economy. Over the course of the next generation, economic opportunity will increasingly be driven by the shift to clean energy, a global transformation that will attract trillions of investment dollars and create, by Biden’s estimate, 30 million jobs worldwide in this decade alone.

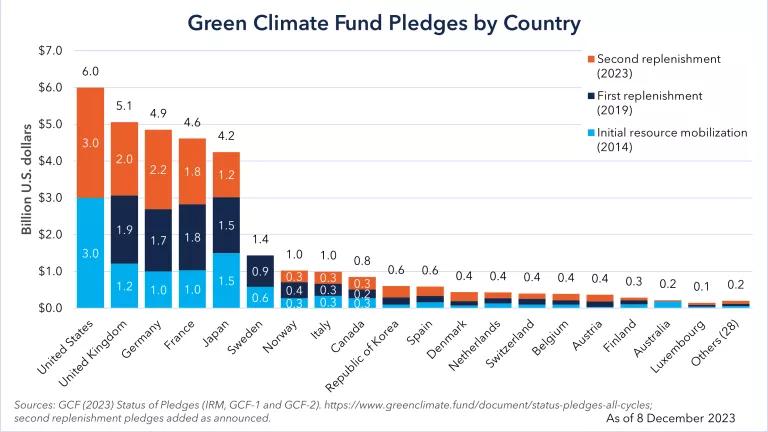

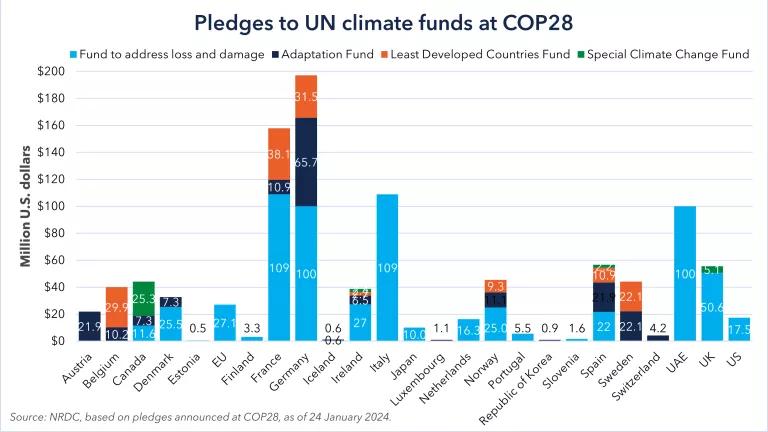

Developing countries must get their fair share. Wealthy nations, to date, have let them down. At Glasgow, the United States and its wealthy counterparts came under renewed pressure to fully deliver on a promised $100 billion a year in climate assistance from 2020 to 2025, and to raise annual assistance after that.

It’s important to recognize also that climate change has inflicted grave harm on many nations that have done little or nothing to bring on the crisis. Because these countries can’t adapt to some of this damage—lands lost to rising seas, for instance—additional finance is needed to compensate vulnerable countries and communities.

A COP26 delegate walks past artist Jonathan Gladding’s 1.5 To Stay Alive painting depicting a young Saint Lucian girl.

Christopher Furlong/Getty Images

Leaders were also working to strengthen their ability to hold each other to account for climate promises, in part by improving the way progress is monitored and reported. They’re scheduled to regroup two years from now, for a critical course adjustment that’s meant to keep the world on track for the progress we need.

The voices of the ancients call out from Glasgow, where nearby stores of coal and iron fueled the Industrial Revolution more than two centuries ago. The future, though, speaks its mind through the voices of youth.

Amid the certain, if measured, progress at Glasgow, youth activists spoke up to remind us that there’s far more to be done than what we've done so far; that a world that fails its children is failing; and that, in so many ways, the climate fight advanced in Glasgow has, truly, only just begun.