What Is Environmental Racism?

This form of systemic racism disproportionately burdens communities of color.

The soil at the former West Calumet Housing Complex in East Chicago, Indiana, was found to contain high levels of lead and arsenic, putting residents’ health at risk. It has since been demolished.

Joshua Lott/Getty Images

The lead in Flint, Michigan’s water, the toxic petrochemical plants in Lousiana’s “Cancer Alley,” the raw sewage backing up into homes in Centreville, Illinois, and the oil and gas projects that overburden some U.S. tribal reservations all have at least one thing in common: They’re examples of environmental racism.

Environmental justice (EJ) advocates have fought these types of injustices for decades, but addressing the root causes has been a protracted and difficult road. Here’s why environmental racism is a systemic issue, how the problem is global in scope, and what we can begin to do in allyship with those who have long sought to dismantle it.

What exactly is environmental racism?

The phrase environmental racism was coined by civil rights leader Dr. Benjamin F. Chavis Jr. He defined it as the intentional siting of polluting and waste facilities in communities primarily populated by African Americans, Latines, Indigenous People, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, migrant farmworkers, and low-income workers.

Study after study has since shown that those communities are disproportionately exposed to fumes, toxic dust, ash, soot, and other pollutants from such hazardous facilities located in their midst. As a result, they face increased risks of health problems like cancer and respiratory issues.

Of course, low-income communities of color have long complained of being treated as dumping grounds for environmental polluters. However, it wasn’t until 1982—after a rural Black community in North Carolina was designated as a disposal site for soil laced with carcinogenic compounds—that those complaints garnered national attention.

The incident prompted civil rights leaders to converge on Afton, North Carolina, where they joined residents in marches and demonstrations. The waste site went in anyway, and it later leached compounds into the community’s drinking water, but a spotlight had been turned on the pattern. This is part of what helped launch the environmental justice movement, which was the response by civil rights leaders to combat environmental racism. In 1983, a member of the Congressional Black Caucus who was at the Afton protests went on to request a General Accounting Office (GAO) study that found 75 percent of hazardous waste sites in eight states were placed in low-income communities of color. The subsequent landmark report, Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States, coauthored by Chavis and Charles Lee for the United Church of Christ, revealed this pattern was even more widespread, and replicated across the entire country.

Eminent sociologist Robert Bullard, known as the “father of environmental justice,” identified additional examples and helped solidify the growing movement. He also expanded the definition of environmental racism as “any policy, practice, or directive that differentially affects or disadvantages (where intended or unintended) individuals, groups, or communities based on race.”

At the time, and in the years since, countless other environmental justice leaders—from Richard Moore to Hazel M. Johnson—also played a significant role in shedding light on environmental racism and its ongoing impacts.

Oscar Sanchez, a participant in the General Iron hunger strike, speaks during a protest near Chicago mayor Lori Lightfoot’s home.

Max Herman/NurPhoto via Getty Images

Why does environmental racism exist?

It’s a form of systemic racism. And it exists largely because of policies and practices that have historically, and to this day, favored the health, well-being, and consumer choices of white communities over those of non-white, low-income communities. Case in point: General Iron is a metal-shredding business that operated in Chicago’s predominantly white, wealthy Lincoln Park neighborhood. In 2018, e-mails showed that city officials from then mayor Rahm Emanuel’s administration pushed the business to move out of this neighborhood after community members complained and to make way for a multibillion-dollar private real estate development. The city then struck a deal to relocate the polluting operation to Chicago’s predominantly Latine, low-income, and working-class Southeast Side neighborhood.

Bullard and others call such land use decision-making by local governments a form of systemic oppression, where race is a dominant factor. While no one wants hazardous waste in their backyard, primarily white, middle- to higher-income communities have always been more successful at preventing it. Conversely, poor communities of color are often perceived as passive and don’t have the clout or resources to challenge the dumping of poison where they live.

And how did those circumstances arise?

Many communities of color still suffer from the legacies of segregation and redlining, which were shaped and enforced through land use policies and local zoning codes. These racist practices discouraged investment in these areas, which eroded asset values and the tax base, leading to crumbling housing and public infrastructure. According to a report by the Tishman Environment and Design Center, polluting industries sought to locate their facilities where the value of land was low, and cities responded by zoning these already-struggling communities for industrial use. Their rights to healthy, thriving spaces were further squandered by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), which has a well-documented history of favoring white communities.

A recent study by the University of California, Berkeley and Columbia University illustrates some of the current effects. It found African American and Latine communities that had been redlined under the discriminatory Home Owners’ Loan Corporation program have twice as many oil and gas wells today than mostly white neighborhoods. That’s no accident.

As is typical for targeted communities, Chicago’s Southeast Side was largely left out of the decision to move the General Iron facility into its neighborhood. So in the fall of 2020, the community fought back by filing a civil rights complaint against the city with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). It was initiated by community leaders, including Peggy Salazar of the Southeast Environmental Task Force (with her successors Olga Bautista and Gina Ramirez) as well as Cheryl Johnson of People for Community Recovery, and supported by partners like NRDC. There was also a hunger strike the following year by other local activists like Oscar Sanchez of the Southeast Youth Alliance and Breanna Bertacchi, a member of United Neighbors of the 10th Ward.

Soon after, Michael Regan, the first African American to serve as EPA administrator, requested that the city conduct an environmental justice analysis as part of the local permitting process. Then in July 2022, in response to the civil rights complaint, HUD announced that an investigation had found Chicago engaging in a pattern of civil rights violations through planning, zoning, and land use policies that routinely relocated polluting businesses from white communities to African American and Latine ones. The city still held out its opposition to HUD following this federal finding, but in May 2023, HUD, the city, and Southeast Side EJ activists announced a precedent-setting settlement, committing the city to a set of reforms to address its racist land use and environmental history and policies.

What forms can environmental racism take?

Environmental racism plays out in many ways and has several cumulative impacts. These include mental and physical health issues, economic inequality, the desecration of cultural spaces, and disproportionate levels of pollution. Given its systemic nature, we could not begin to cover every instance, but here are some examples:

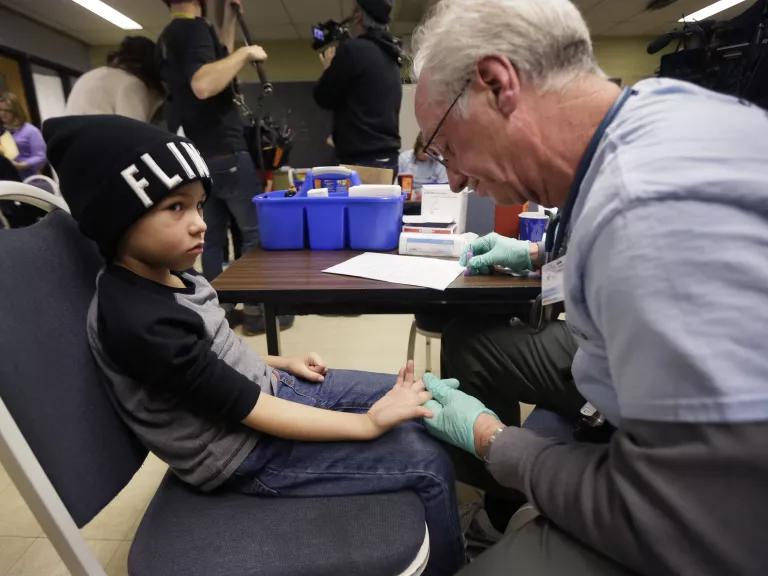

Students at Eisenhower Elementary School in Flint, Michigan, being tested for lead after the toxic metal was found in the city's drinking water in 2016.

Carlos Osorio/Associated Press

- Flint and Benton Harbor, Michigan: In 2014, a water system contaminated by lead turned into a crisis for the city of Flint. Four years later, neighboring Benton Harbor experienced the same thing.

Both communities, which are predominantly Black and low-income, already suffered from a history of state and local government mismanagement. A subsequent failed response to this crisis resulted in years of lead leaching through pipes into drinking water. Lead exposure is linked to health consequences from heart and kidney disease in adults to impaired brain development in children.

Water experts, community leaders, lawyers, and advocates came together with residents to resolve the crises, which included replacing lead pipes and securing alternative water sources and/or filters. What happened in Flint and Benton Harbor also helped galvanize a national conversation calling for a systemic solution to lead exposure. The Biden administration has since committed to replacing all U.S. lead service lines within the next 10 years.

A group of water protectors on the Standing Rock Sioux reservation, North Dakota.

Jolanda Kirpensteijn

- Dakota Access Pipeline: The construction of this 1,200-mile pipeline for transporting crude oil began in 2016. Oil and gas giant Energy Transfer Partners initially proposed a path across the Missouri River just north of the predominantly white community of Bismarck, North Dakota. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers rejected that route, in part because of the threat it posed to the state capitol’s water supply. But then the Army Corps approved the pipeline to cross under the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s primary water source, and it disregarded their concerns over the desecration of tribal sites and potential water contamination in the event of an oil spill.

The tribe’s yearlong protests and legal challenges drew international attention. Then, in response to the tribe’s lawsuit, a federal court ruled in 2020 that permits for the project were illegally approved. It ordered the government to conduct the thorough review of environmental impact initially sought by the Standing Rock Sioux. The review is ongoing.

Cancer Alley stretches 85 miles from New Orleans to Baton Rouge, where a dense concentration of oil refineries, petrochemical plants, and other chemical industries reside alongside suburban homes.

Giles Clarke/Getty Images

- Louisiana’s Cancer Alley: Over the last several decades, this 85-mile stretch between Baton Rouge and New Orleans became the de facto sacrifice zone for mile after mile of gas and oil operations. This has resulted in an alarming number of health risks for the majority Black and low-income communities, which is how the area got the nickname “Cancer Alley.” In fact, 7 of the 10 census tracts with the country’s highest cancer risk levels from air pollution are found here.

For a time, Cancer Alley residents protested these corporate polluters with little success. But that’s begun to change, and Sharon Lavigne is leading the way. She’s helped organize other residents in her community to push back against new polluters seeking to set up shop in their parish—and won. Plus, the EPA finally weighed in too. In a 56-page letter, it accused local and state officials of turning a blind eye to residents being subjected to large amounts of cancer-causing chemicals spewing into the air, soil, and water.

Does environmental racism only happen in America?

It happens all over the world—although what it’s called or how it’s framed can be different. Race is used as the primary mechanism to distribute environmental benefits and harms in the United States, but in other countries, caste, ethnicity, and class can function in similar ways. Still, the outcomes are the same. In northern Mexico, for example, the mass shipment of used car batteries from the United States and other nations to metal recyclers—located there to profit from lax occupational and environmental laws—have led to high levels of lead poisoning among workers, and the contamination of soil, air, water, and livestock.

Meanwhile, at least 23 percent of e-waste from developed nations is exported to informal recycling operations in China, India, and West Africa’s Benin, Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Liberia, and Nigeria. The local populations doing the work use rudimentary techniques because they lack the technology to handle e-waste more safely, and there isn’t much in the way of environmental regulations. That has exposed entire towns to toxic materials, which have caused illness and contamination.

Environmental racism also rears its ugly head in the overall climate crisis. The world’s wealthiest economies produce 80 percent of global emissions from coal, oil, and gas, but it’s developing nations that bear the brunt of global warming’s impacts.

An e-waste dumpsite in the Agbogbloshie slum of Accra, Ghana, was a former wetland in the 1960s and the home of refugees who fled the conflict in northern Ghana during the 1980s.

Cristina Aldehuela/AFP via Getty Images

What must we do to begin to end environmental racism?

There’s so much to do, and we can all play a part. First, it’s important to recognize that the answers are rooted in the environmental justice movement. As environmental justice leaders who met at the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit in 1991 made clear: If environmental racism is forcing poison upon low-income people of color, justice then does not entail shifting those inequities to others (in the United States or abroad), but remedying them as well as preventing them in the future.

That starts with listening to the communities most impacted by environmental racism and the broader climate crisis. It means ensuring they have a leading role in the decision-making processes regarding the policies that shape where they live and work. And it means holding those in power accountable for honoring the rights of all people to clean air, clean water, and healthy communities. In other words, true environmental justice requires dismantling the racist structures that created this problem.

This is finally being acknowledged on a global scale. A recent United Nations report stated, “There can be no meaningful solution to the global climate and ecological crisis without addressing systemic racism.” Global efforts have also given birth to a dynamic and vocal climate justice movement that centers intersectionality and cross-border solidarity. The goal is to advocate for solutions that lead with and drive social transformation. At the most recent U.N. Conference of the Parties (COP27), environmental justice advocates successfully pushed the U.S. Department of State to drop its opposition to the global loss and damage fund. That said, leaders, particularly in the Global North, must do more, including meeting global commitments to climate mitigation, adaptation, and funding.

Leaders of Benton Harbor, Michigan, announced in November 2021 that the city is accepting bids from contractors for an ambitious project to replace all lead water pipes no later than 2023.

Don Campbell/The Herald-Palladium via Associated Press

In the United States, the Biden administration created the Justice40 Initiative to direct 40 percent of all climate and clean energy federal investments to communities identified by the Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool as overburdened by pollution. And both the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) provide millions to fund this work. Those are important steps forward, but as NRDC community solutions advisor Mikyla Reta noted, there are also provisions in the IRA that support polluting industries, like oil and gas drilling. In addition, with segregation and its legacy still very much alive, implementing IIJA and IRA, and spending the money in equitable ways, poses challenges.

There’s also a continued role to play by environmental organizations like NRDC. Historically, Big Green—primarily white environmental organizations—has had little or no involvement in the environmental struggles of people of color. That’s what prompted environmental justice leaders in 1990 to cosign a widely shared letter to these groups, including NRDC, accusing them of racial bias and challenging them to address issues in EJ communities. In response, some mainstream environmental organizations began to diversify their organizations and developed their first environmental justice initiatives, but much work remains. First, these organizations must actively continue to become more diverse spaces that reflect the communities disproportionately impacted by environmental issues. Also, they must continue finding ways to serve as allies to environmental justice partners and center them when helping to shape policy.

And though the response must largely be systemic, there are some things you can do too. For example, you could learn about the environmental hazards in your community and, if necessary, demand your representatives address problems. You can also read up on the environmental justice movement and find local EJ organizations to support so that they can continue to do this critical work.

Helping to end environmental racism is going to take all of us. For low-income communities of color besieged by it, the change can’t come soon enough.

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

When Customers and Investors Demand Corporate Sustainability

Air Pollution: Everything You Need to Know

The Environmental Justice Movement