Utility Accountability: How Do Utilities Make Money?

Our grid hasn’t kept up to its potential—and it's holding back our development of clean energy and the deployment of the innovative, clean technologies. Too often, utilities are incentivized to build too much of things we don’t need and not enough of things we do need.

The way we generate and use electricity is changing fast. The transition in how we generate electricity is being driven in large part by the growing share of increasingly cheap renewable energy. Compared to twenty years ago, the U.S. generates 66 times more wind energy and 144 times more solar energy.

New technologies are also radically changing the way we use power: electric vehicles, energy storage, super-efficient electric heating and cooling systems, and software that can manage energy use in real time. These technologies can not only save us money and make us more comfortable; they’re also cleaner. To avoid catastrophic climate change, we need to scale them up as quickly as possible. That means changing the way we think about the system that gets electricity from the place it's generated to the plug in your home: the electric grid, or simply "the grid."

Developing a Modern Electric Grid

All these advances mean we need to continue to develop our electric grid. Fifty years ago, the grid sent power in one direction, from point A to point B: from big, centralized fossil fuel power plants to homes and businesses. Today, rooftop solar panels have turned homes and businesses into thousands of little power plants, selling electricity they don’t use back to the grid to supply their neighbors. Smart appliances let us to dial our energy use up and down to manage demand and save money. Batteries can store electricity when it's plentiful (like the middle of the night) and use it later when it's scarce.

It's like the difference between listening to the radio and using the internet. On the radio, information flows in one direction—from the radio station to you, who can only passively listen. That's like the old-school electric grid. On the internet, you might listen to a song on YouTube, leave a comment about it, text it to a friend, then share it on Facebook; you can do all this on multiple devices at home and at work. Information is constantly flowing back and forth between many users. If one server goes down, traffic is instantly rerouted around it to keep your connection going. Our electric grid has the potential to work more like the internet: distributed, resilient, and responsive.

But our grid hasn’t kept up to its potential—and it's holding back our development of clean energy and the deployment of the innovative, clean technologies. Too often, utilities are incentivized to build too much of things we don’t need and not enough of things we do need.

What’s Holding Us Back

Why? In part, because the way utilities are regulated and paid has hardly changed in a hundred years.

Here’s the basic idea behind this century-year-old utility business model: utilities make profit by investing in the infrastructure, like pipes and wires, that provide energy services to customers.

In some states, utilities own and operate power plants too, but in Illinois power plants are required to be owned by different companies from the poles and wires that bring electricity to your house (although power plant owners and utilities in some cases are both subsidiaries of the same company, as is the case with ComEd and Exelon).

Utilities are regulated monopolies, meaning they’re the only companies legally allowed to deliver electricity or gas to people within a geographic area. In Illinois, electric utilities are required to deliver reliable electricity that’s as clean and low-cost as possible—in the words of the law, “adequate, efficient, reliable, environmentally safe and least-cost public utility services”. In exchange, utilities are allowed to recover their costs, plus a profit.

How the Process Works

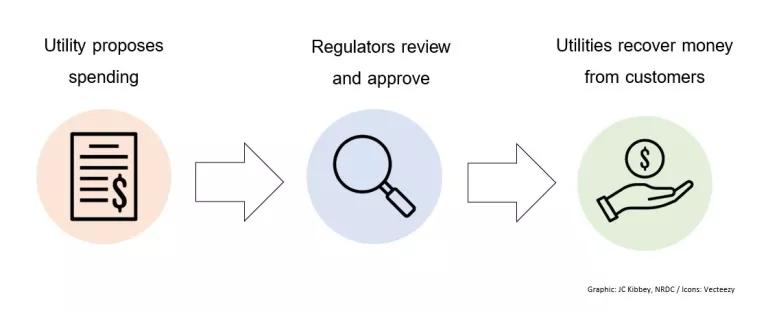

The regulators at the Illinois Commerce Commission (ICC) are charged with reviewing and approving these costs to make sure utilities’ spending is “prudent and reasonable.” If the ICC finds that their spending meets this standard, utilities are granted a “reasonable opportunity” to collect it back from us on our bills. If that spending isn’t prudent and reasonable, utilities aren’t allowed to collect it on our bills. (These rules apply to investor-owned utilities like ComEd and Ameren; municipal utilities and rural cooperatives operate differently).

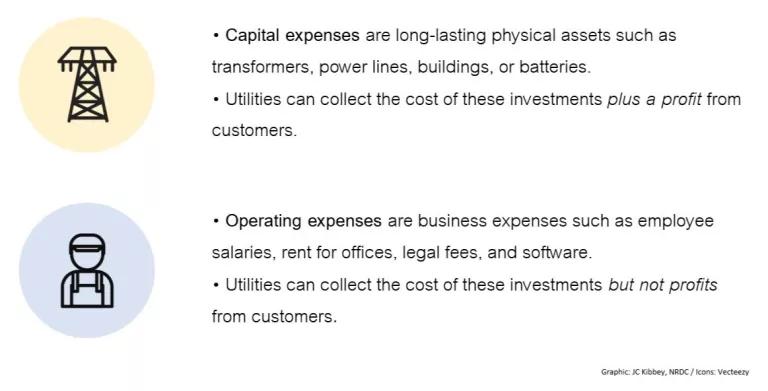

But all utility spending isn’t the same: there are two types of expenses for utilities, and they are treated differently. The first is operating expenses: costs for the day-to-day operation of business, which includes things like workers’ salaries, paper to print bills and stamps to mail them, and rent for offices. The second is capital expenses: the physical infrastructure that makes up the electric grid, including things like wires, poles, transformers, and substations.

Utilities can collect their spending on operating expenses from you and me, on our bills. In practice, they almost always cover their costs, but they don’t get anything extra beyond what they spent. So, if a utility spends $100 on operating expenses, it collects $100 back, spread out across all the bills people pay to that utility. They don’t profit.

But with capital expenses—that is, physical infrastructure, like poles and wires—utilities can collect the money they invested plus an additional percentage they keep as profit. So, if a utility spends $100 on capital expenses, they might collect $110 on our bills, with $100 paying for the wires and poles and $10 going towards profits.

Utilities fund capital expenses with a combination of shareholders’ money and money borrowed from banks. No one would lend them money at zero percent interest, nor can we expect their shareholders to invest their money at zero rate of return, so it’s reasonable for utilities to charge a little more than they’re spending to pay back banks and shareholders.

But there’s a conflict at the heart of this business model.

On one hand, utilities are required to deliver “environmentally safe and least-cost services.” And there are ways utilities can meet the needs of the grid without any capital spending at all, for example with “demand response” programs that reward customers for using less electricity when there’s lots of demand (like on a hot August afternoon when everyone is running their air conditioner).

On the other hand, the only way utilities make profits is by spending money on physical infrastructure (e.g., poles and wires). The law says they should spend the least they can while providing quality, environmentally safe service, but when it comes to their bottom line, utilities are incentivized to make more costly investments. The more they spend on physical infrastructure, the more profit they stand to make.

Investing in Clean Energy

Utilities spending money isn’t inherently a bad thing! To avoid catastrophic climate change, we need to move as quickly as we can to decarbonize our electric sector, and that will require investment in the grid. Those investments are critical. The problem is that utilities are incentivized to spend money on more physical infrastructure, whether or not it best supports a clean and affordable grid. They have little incentive to enable clean energy, for instance, or to keep bills low for people who have low incomes.

Here’s a hypothetical example that highlights the issue: several large new apartment buildings have been built in a neighborhood, so the area is now using more electricity than the local electric grid is able to provide. There are two ways to address this: one is a $50 million project that brings more power into the neighborhood by building new high-tension wires and new substations; the other is a $10 million project to reduce demand by implementing energy efficiency measures and installing batteries. For this example, let’s say the utility has a return on equity of 10%, meaning that they make a 10% profit on whatever they spend on capital expenses.

If the utility chooses to build the $10 million project, it would make $1 million in profit, and meet their public charge of providing “least-cost” service. But if it chooses the $50 million project, it will make $5 million in profit. They haven’t provided the “least-cost” solution, but they’ve made more money. Their shareholders will probably like this better, but it will also leave customers paying more than they should.

In theory, under our current system of regulation, regulators would figure out that the utility could meet this system need at lower cost and with less environmental impact, deny the $50 million project, and tell the utility to come back with a more affordable solution. In practice, this often doesn’t happen. In an ideal world, utilities would make money by making investments that provide customers with the cleanest and most affordable service regardless of whether it involved building something.

Changing the Way Utilities Do Business

The problem isn’t necessarily that regulators aren’t doing their best, but that a) utilities know a lot more about their system than anyone else, so they may be the only ones who know about the lower-cost solution, b) regulators and advocates are vastly outgunned by utilities, which can hire lots of high-powered attorneys and engineers to argue their case (ironically, the fees utilities pay to their lawyers and engineers are passed along directly to us on our bills, as “operating expenses”), and c) the laws may be written in a way that ties regulators’ hands.

This approach to regulation gives utilities a perverse incentive to build bigger and more expensive things, even when cleaner and more affordable solutions like energy efficiency are available. It will be hard to persuade utilities to pursue cleaner and more affordable grid investments as long as our system of regulation is nudging them in the other direction.

The only way to change this is rewriting those laws so that the utilities’ incentives and customer needs are more aligned—fortunately, many states around the country are doing just that in some form: among them Colorado, Hawaii, New York, California, Washington, Nevada, and Minnesota.

Illinois has taken some tentative steps in this direction, but still incentivizes utilities to over-spend on capital, hamstrings regulators’ oversight of utility spending, and offers few incentives to improve performance in most areas. We have a long way to go.