Research: Displacement in the Face of Climate Change

The past five years have been the warmest ever recorded on record globally, and spring flooding, hurricane and wildfire seasons are once again upon us, with summer months and their expected warmer-than-average heat not far behind. Between hurricanes in the southeast and wildfires in California, over 1.2 million people were displaced by climate-related disasters in 2018 alone.

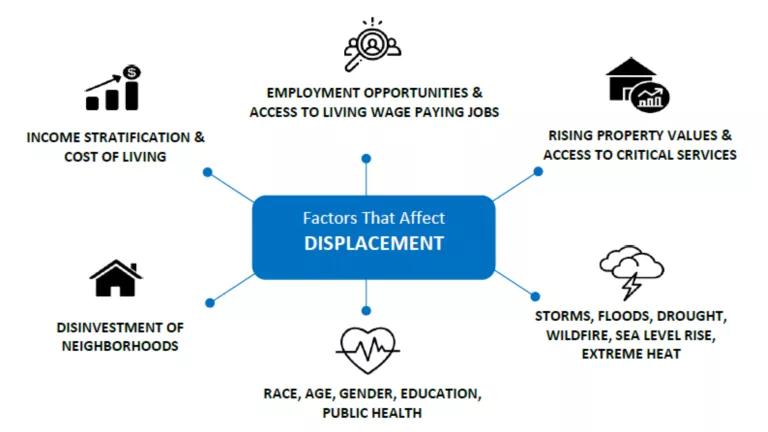

More than ever, where and how we live is being driven by climate change. Climate change and economic disparity lay bare the legacy of intentional, racially discriminatory systems that disproportionately hurt low-income and communities of color. What often happens is that the very solutions that curb emissions and protect from these impacts can also cause displacement. Now, the COVID-19 crisis is further stressing these existing disparities. Renters, with fewer resources and less recovery assistance, are especially vulnerable to displacement during a crisis. Combine that with the fact that more U.S. households are headed by renters than at any point since 1965—many of them people of color or low-income with job insecurity in the face of a pandemic—and you’ve got a potential displacement emergency.

The Strong, Prosperous, and Resilient Communities Challenge (SPARCC) sponsored a literature review and survey to uncover the links between climate and displacement. Working with the Urban Displacement Project (UDP) at the University of California Berkeley and EcoAdapt, SPARCC sought to better understand the interrelationships between the pressures exerted by climate change and the unintended consequences of investments in climate adaptation and mitigation, and how practitioners are working to reduce both climate and displacement risks.

Research findings

The literature review synthesized findings from 384 studies, reports, and articles published from the 1970s to today and shows historically significant inequities in that persist today. In coastal states like New Jersey, housing continues to be built more rapidly in flood prone places than in low risk areas. As a result, these coastal communities are directly affected by floodwaters while nearby areas face the indirect risk of displacement due to the housing shortages that result when receiving people exiting the flood zones.

The accompanying national survey of 179 respondents spanned multiple sectors (e.g. housing, parks, environmental justice, or transit). It found that for 74 percent of practitioners, day-to-day issues such as the cost and availability of affordable housing ranked as their highest priorities—above climate change impacts. However, an overwhelming 91 percent agreed that climate change is having or is likely to have a significant effect on their communities, with 64 percent taking direct action to address the effects of climate change. Barriers to taking action on climate included money and resources, in addition to a lack of technical expertise and clarity on viable options.

The literature also found that green investments including housing near transit and parks enhance our resilience to climate change by lowering emissions or absorbing floodwaters, but their benefits can be tempered by higher housing costs. Energy-efficient infrastructure and rooftop solar also lead to higher housing values, potentially countering the effect of lower energy costs.

“We need to figure out how to stabilize these neighborhoods, and improve their resilience, without spurring displacement,” offered one survey respondent.

Resilient solutions from communities

Encouragingly, as stated, 64 percent of respondents are, in fact, taking into account climate change in their work, motivated by climate justice and equity values. These practitioners are especially focused on community engagement and offering a diversity of housing options or co-locating reliable transit and affordable housing.

In Atlanta, for example, the SPARCC partner the Partnership for Southern Equity (PSE) was noted as a case example for focusing on connecting communities and increasing quality of life through its Equitable Transit-Oriented Development program. PSE is working with the Atlanta Regional Commission to engage community members in transit planning and understanding transit needs so the city can become less car-dependent while avoiding displacement.

Practitioners surveyed offered other ideas, including prioritizing more ways to integrate passive heating and cooling in affordable housing, relocating people out of vulnerable areas and protecting future land for housing, as well as implementing transitional housing programs for those who are displaced. As in the literature review, community land trusts (CLT)—nonprofit corporations that develop and oversee affordable housing and other community assets on behalf of a community—and community ownership of land were identified as anti-displacement strategies that may help increase community resilience.

In one example, The Caño Martín Peña CLT in Puerto Rico allowed residents to return more quickly than other areas after Hurricane Maria. CLTs like this may allow communities to rebuild without the risk of climate-driven gentrification.

Our research affirms that the environment, housing, health, racial equity, and economic opportunity are inextricably linked. While there may be a gap between what is being done and what can be done, the survey underscored that displacement and gentrification don’t have to be inevitable in making our cities climate ready.

Opportunities

There is an opportunity to continue to find creative ways to elevate and implement innovative policies and solutions that are being identified by those experiencing the interconnections first-hand.

“There is a need for a countywide mandate for anti-displacement that brings together different agencies […] to look at development with an anti-displacement lens and language to keep residents in place as healthy developments grow,” stated a survey respondent.

The research also shows that while anti-displacement policies have the potential to mitigate the threats of climate change and other public health threats, supporting thoughtful and informed leadership by local jurisdictions and communities is key to the timing and effectiveness of putting those policies into practice. While we don’t yet know how this current health and economic crisis will affect housing in America how we respond during this time may inform our ability to respond to climate change. A major takeaway is that strategies that consider the links between disasters, health, equity, and community investment—and that put people at the forefront—can create long-term solutions and more resilient and equitable places to live.