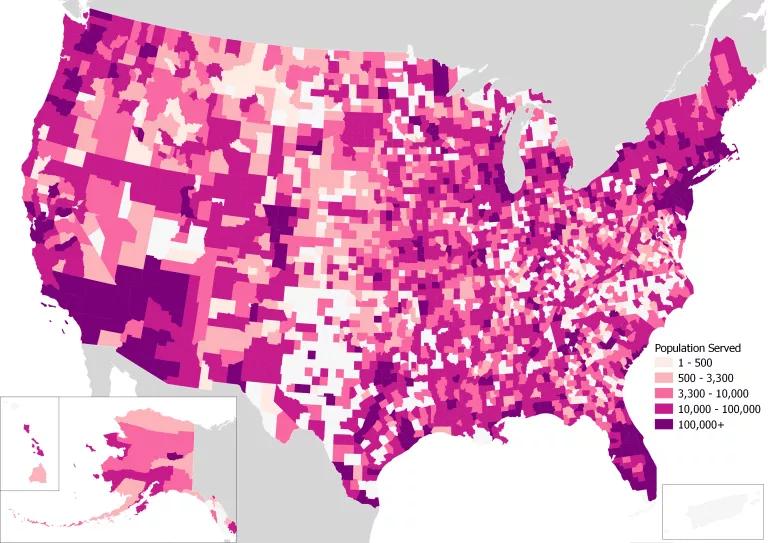

Populations served by drinking water systems with 90th percentile lead samples above 1 part per billion

Kristi Pullen Fedinick (NRDC)

A new NRDC analysis of the most recent EPA data shows that between January 1, 2018, and December 31, 2020, 186 million people in the United States—a staggering 56 percent of the country's population—drank water from drinking water systems detecting lead levels exceeding the level of 1 part per billion (ppb) recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics to protect children from lead in school water fountains. More than 61 million people were served by drinking water systems that detected lead levels that exceeded the limit of 5 ppb set by the Food and Drug Administration for bottled water, which NRDC recommends as a tap water standard. Seven million people were served by systems that exceeded the EPA’s Lead Action Level of 15 ppb—a level that is supposed to trigger additional actions by water systems to reduce their lead levels. The EPA and health experts agree that no amount of lead is safe, so any level above zero is not considered safe.

Though the numbers we find in this assessment are quite large, it is possible that we are missing communities with significant issues with lead in their water. For example, the federal dataset we used for this analysis indicates no lead detections for drinking water systems in Puerto Rico. This is likely due to underreporting. EPA audits of the data we used to develop these estimates found that states failed to report 92 percent of Lead and Copper Rule health-based violations to the EPA.

While the findings of this assessment do not mean that every person served by a drinking water system with lead detections above certain limits has lead in their water, the numbers do show that lead in drinking water is a problem we should all care about.

Map from NRDC’s Watered Down Justice report showing the intersection of length of time out of compliance with the the racial, ethnic, and language vulnerability by county (June 1, 2026 to May 31, 2019).

Kristi Pullen Fedinick (NRDC)

Background

It has been nearly six years since the Flint crisis galvanized a movement. Communities have united to find solutions to the problems in their water systems. In response to public pressure, some states have strengthened their lead in tap water protections or are seeking to remove lead from drinking water in schools and child care centers, and some water systems have pulled thousands of lead service lines from the ground. Though the picture seemed grim in 2015, with more than 18 million people served by drinking water systems that violated the Lead and Copper Rule of the Safe Drinking Water Act, the last few years have brought some glimmers of hope. As my colleague Erik Olson notes in a separate blog, the Biden administration and other policymakers have been moved by the strong public demands for action, proposing to remove every lead service line in the country and to seriously address the long-standing scourge of lead-contaminated tap water.

While some progress has been made over the years, much more still needs to be done. The EPA has estimated that 6 million to 10 million lead service lines are in use across the county. This means that countless families across the country get their water from pipes that are made of a chemical—lead—that can harm them. And these burdens may fall disproportionately on the shoulders of Black, Indigenous, and other people of color.

The Safe Drinking Water Act

Created in 1974, the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) is one of our country’s bedrock public health laws. It aims to protect the drinking water supplies of our nation by setting standards that local water utilities must adhere to. When a drinking water utility fails to meet the standards set by the law, it can receive a variety of violations including health-based (a failure to adequately treat the water, e.g., not removing arsenic or not properly disinfecting to kill parasites and bacteria), monitoring (a failure of a system to properly test for contaminants), or reporting violations (such as a failure to report lead results to the public or government officials).

The SDWA currently regulates about 100 contaminants including some naturally occurring chemicals (e.g., arsenic), microbial contaminants (e.g., E. coli), man-made compounds (e.g., Atrazine), and other contaminants that can impact human health. In recent years, largely due to the mass poisoning of the citizens of Flint by their state and local water supplier, lead has emerged as a contaminant of significant public concern.

Key Analysis Findings: Lead in Drinking Water Is a Significant Issue in Many Parts of the County

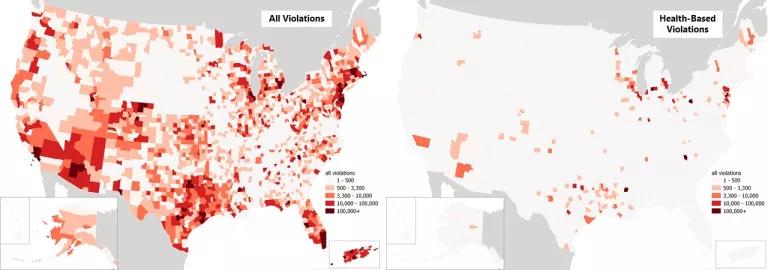

To identify areas of the country with higher potential for lead exposure from drinking water, NRDC re-analyzed and updated our previous analyses of violations of the EPA's Lead and Copper Rule and the results of water systems’ reported lead testing. Our new analysis found that between January 1, 2018, and December 31, 2020:

- 28 million people were served by 7,595 drinking water systems with 12,892 lead violations

- 3 million people were served by 372 drinking water systems with over 530 health-based violations for lead

Populations served by drinking water systems with Lead and Copper Rule violations

Kristi Pullen Fedinick (NRDC)

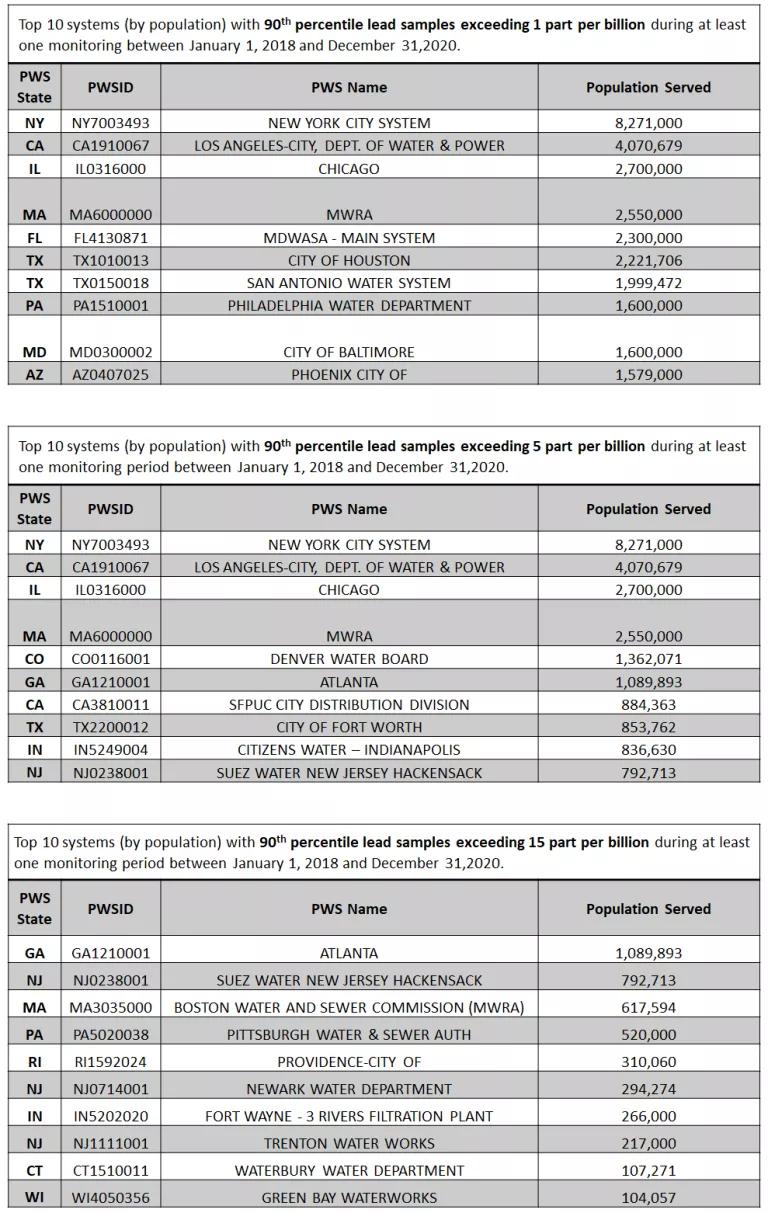

Of the systems with violations during the study time frame (January 1, 2018—December 31, 2020), the top 10 systems by population served were:

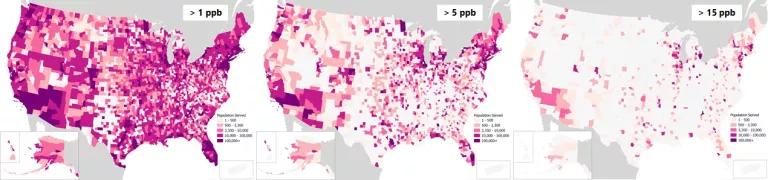

In addition to violations, we also analyzed the data to find areas of the country with lead levels that exceeded 1 ppb, during at least one monitoring period between January 2018 and December 2020. Shockingly, we found:

- 186 million people were served by 18,694 drinking water systems with 90th percentile lead samples above 1 ppb—the AAP recommended limit for schools.

- 61 million people were served by 4,949 drinking water systems with 90th percentile lead samples above 5 ppb—the FDA limit for bottled water.

- 7 million people were served by 1,085 drinking water systems with 90th percentile lead samples above 15 ppb—the EPA action-level exceedance.

Populations served by drinking water systems with 90th percentile lead samples above 1, 5, and 15 parts per billion.

Kristi Pullen Fedinick (NRDC)

Removing Lead Must Be a Priority

This analysis shows the extraordinary scale of lead-related drinking water issues across the country. Worryingly, this assessment very likely only shows the tip of the iceberg. The EPA’s own audit revealed that only 8 percent of the important health based standard of the Lead and Copper Rule (treatment techniques) were reported to the SDWIS/FED—the data source available to the public for these types of analyses. This EPA audit was reported in 2008, though a subsequent Government Accountability Office audit confirmed widespread under-reporting. Indeed, EPA’s former head of enforcement, Cynthia Giles, stated in 2020 that the agency's and Government Accountability Office “audits describe a lead rule reporting system that is completely broken” due to widespread under-reporting. This means that many communities with significant lead issues may not be represented in these analyses.

As discussed in greater detail in this blog, to protect the millions of people across the country that could be impacted by lead in their drinking water, decision makers must take immediate action to protect populations from lead and other contaminants by:

- Implementing the Biden administration proposal to remove “100 percent” of lead service lines in full, with high priority placed on replacing pipes in environmental justice communities and/or other communities that are disproportionately impacted by drinking water and other forms of environmental contamination and degradation.

- Fixing our drinking water laws and rules by substantially strengthening the Lead and Copper Rule and effectively enforcing it, while letting citizens more easily sue for relief from contaminated water.

- Providing immediate funding for both lead- and non-lead- related drinking water infrastructure projects, with priority given to environmental justice communities and/or other overburdened communities that are in most in need of assistance.

- Enforcing the Lead and Copper Rule (and other SDWA rules) assuming an undercurrent of structural racism that creates an unequal playing field for different communities.

- Strengthening small systems to ensure their ability to comply with the law.

Millions of Americans drink tap water served by toxic lead pipes.

Tell the EPA we need safe drinking water!

Tell the EPA we need safe drinking water!

There is no safe level of lead exposure. But millions of old lead pipes contaminate drinking water in homes in every state across the country. We need the EPA to do its part to replace lead pipes equitably and quickly.