Indigenous Communities Lead Way to Boreal Forest Protection

This post was written by Jennifer Skene

Yesterday was Indigenous Peoples’ Day, a celebration of the Indigenous communities living in North America since long before the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa Maria set sail from Spain. States, cities, and universities across the U.S. are embracing Indigenous Peoples’ Day as a counter-celebration to Columbus Day. While Indigenous Peoples’ Day is certainly about acknowledging the centuries of genocide that followed Columbus’ fateful 1492 “discovery” of the Americas, it’s also about recognizing the diverse cultures and incredible accomplishments of Indigenous communities. In the conservation of Canada’s boreal forest there’s a lot to celebrate, as Indigenous Peoples are leading the way in protecting this treasured forest and its species for future generations.

Indigenous Peoples have lived in and relied upon the boreal forest for millennia, and today over 600 Indigenous communities live in the boreal region. Many communities’ cultures are inextricably tied to the forest and species like the boreal caribou. However, Indigenous communities across Canada face increasing incursions from industry into their traditional territories, undermining their right to control their land and threatening their cultural practices and ways of life.

To protect their homelands, many Indigenous communities are leading the fight for boreal forest protection and providing models for sustainable economic development. Their efforts, including comprehensive land-use plans, boreal caribou management, and Indigenous-run protected areas, have preserved traditional territories and protected some of Canada’s most treasured wildlife. The following are just a handful of the myriad examples of Indigenous leadership in boreal forest protection:

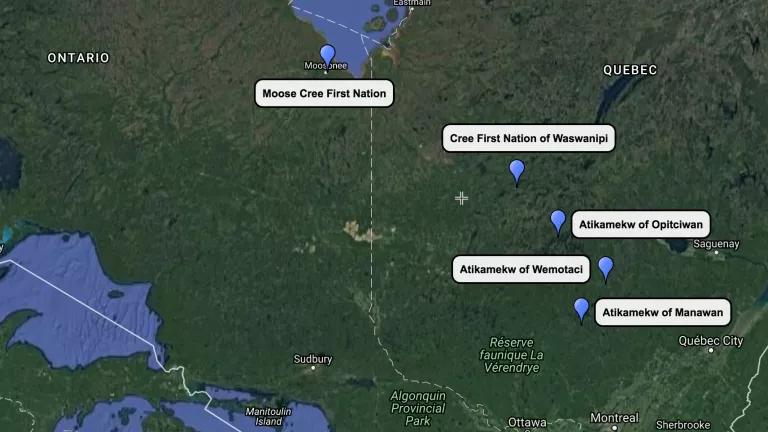

- The Cree First Nation of Waswanipi in the Broadback River watershed are one of the strongest voices in boreal forest protection. They have fought for over a decade to protect the remaining 10 percent of intact traplines on their ancestral homeland, which overlap with critical caribou habitat. In 2011, the Waswanipi Cree released the Mishigamish protected area proposal for the Broadback region, and in 2015, they succeeded in protecting almost 2.3 million acres of forest north of the Broadback River. Yet, while an important step in the region’s conservation, the 2015 agreement sadly falls far short of the Waswanipi Cree’s proposal and protects only a fraction of their traditional territory. As road construction and logging operations continue to threaten the region, the Waswanipi Cree are on the front lines, advocating for the protection of their homeland.

- The Atikamekw First Nation in Quebec is fighting to protect their land from logging without their consent. In 2012, the Atikamekw communities of Opitciwan and Wemotaci erected roadblocks to stop logging operations in their territory until the Quebec government acknowledged their authority over their own natural resources. In September 2014, the Atikamekw Nation declared their sovereignty over 19.7 million acres of land between Montreal and Lac Saint-Jean, and shortly afterwards announced they would not permit any logging in the region without their consent. In August 2017, the Atikamekw scored a significant legal victory when they were granted an injunction against logging operations in their territory.

- The Moose Cree First Nation are currently drafting a Homeland Protection Plan to restore the North French River watershed, spanning 1.6 million acres across Ontario and constituting 10 percent of the Moose Cree’s traditional territory. Over a period of decades, the region has been impacted by mineral exploration, logging, and road construction. In 2002, the Moose Cree declared the North French River to be permanently protected, and ever since, they have defended the area from industrial development, reaffirming their declaration of protection in 2015. In 2017, the Moose Cree unanimously rejected an exploratory drilling proposal that could degrade the region. Due to the Moose Cree’s opposition, Ontario has placed its review of the project on hold, pending consultations with the community.

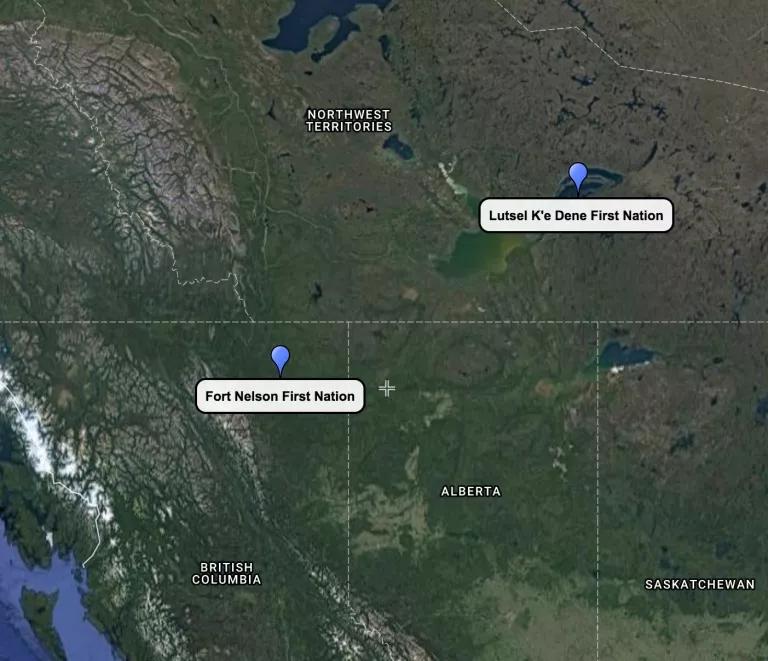

- Last week, when every single Canadian province missed the deadline for submitting caribou range plans, the Fort Nelson First Nation in British Columbia demonstrated the kind of leadership on caribou protection that the provinces have thus far failed to show. The Fort Nelson First Nation’s Medzih (boreal caribou) Action Plan (MAP) to protect and recover caribou populations within their traditional territory is the first and only recovery plan in British Columbia to spatially identify and protect critical boreal caribou habitat. With MAP, Fort Nelson First Nation has embraced their responsibility to protect the boreal caribou through sustainable economic development and caribou recovery initiatives and shown Canada’s governments a workable model for meaningful caribou protection.

- The Lutsel K’e Dene First Nation in the Northwest Territories led a successful effort to create Thaidene Nene (“Land of the Ancestors”) National Park Reserve, a 3.5 million-acre protected area, in their homeland. The region is an important habitat for numerous species including barren-ground caribou, moose, bears, and songbirds. Thaidene Nene provides a model for sustainable, indigenous-led economic development. The Lutsel K’e Dene will co-manage the park reserve, providing employment in park stewardship and tourism as part of the National Indigenous Guardians Network, which “draw[s] on Indigenous knowledge and science to monitor industrial development and care for the land and water” and recently received $25 million in funding from the federal government. This has set the stage for a diversified “conservation economy” that can serve as a model for other communities.

In crafting plans for protecting the boreal forest and caribou, Canada’s federal and provincial governments should learn from these examples of Indigenous leadership. Many Indigenous communities have uniquely intimate knowledge of the boreal forest built up over generations and can provide unparalleled insight into how best to protect boreal ecosystems. Canada’s governments should work with Indigenous communities to craft meaningful policies grounded in their right to govern the use of their land, following the principles articulated in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). Indigenous Peoples have been leading the way in protecting Canada’s most precious ecosystems and species. Now it’s time for Canada’s non-indigenous governments to follow suit.