Driving Ambition, Action, and Equity at COP28 (Part 2)

At COP28, countries, companies, investors, and other decision-makers sent a clear signal to spur greater action now and increase ambition this decisive decade.

Pathway at COP28 to the Blue Zone Pavilions.

Jake Schmidt, NRDC

We came into COP28 with the expectation that leaders would deliver ambition, action, and equity in the global response to climate change, and to follow through on implementation. We leave COP28 with a clear-eyed view:

“It’s time now to turn global ambition into climate action - and there’s not a moment to lose.”

Since the Paris Agreement was adopted there has been a two-part architecture to international climate action. The first part of that structure was a negotiation on a set of agreements that would define or implement actions that the international community would deliver to tackle the climate crisis. The second part, which has both grown in numbers and importance, is a set of political declarations, multi-stakeholder coalitions, specific national actions, and other efforts that both deliver on the goals of the Paris Agreement and build coalitions that can implement actions more aggressively than can be accomplished through agreements of the 194 countries that are Parties to the Paris Agreement. Both are critical, but the “action-agenda” pieces have played an even larger role since the Paris Agreement – and that is a promising sign. At COP28 we witnessed key deliverables on both pieces of that architecture – the negotiated agreements and the action-agenda.

This is part 2 highlighting the political commitments, new announcements, and other key elements that were mobilized at COP28 – the action-agenda. In part 1 we covered the key elements of the negotiated agreement.

Prior to COP28, implementation of current actions, delivery of the various pledges, and the promised long-term targets of countries, companies, investors, and other decision-makers could put us on a trajectory for 1.8°C. That is an “optimistic scenario” based upon everyone delivering both their binding actions and their announced targets. To put the world on track for 1.5°C, the world needs to both deliver on its promises and drive additional actions by 2030 – to close both the “implementation” and “emissions” gaps.

COP28 came at a critical moment in the push to step-up action this decisive decade.

Leaders at COP28 committed to new actions and declarations to help close these gaps with new signals on:

- the response to the Global Stocktake,

- phasing-out fossils,

- increasing renewable energy and energy efficiency,

- setting up a loss and damage fund,

- mobilizing more finance,

- protecting forests,

- decarbonizing industry,

- climate-smart food and agriculture,

- deploying smart transportation,

- city and state/province action, and

- climate and health.

Global Stocktake Sends Course Correction Signal this Decade

The negotiated response to the “Global Stocktake” set some key targets that can help to further put us on track this decade, if delivered, including:

- Setting a benchmark to cut emissions 43 percent by 2030 and 60 percent by 2035 below 2019 levels, and to set economy-wide 2035 Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) that should be guided by these benchmarks

- “Accelerating action in this critical decade” to transition away from fossil fuels in energy systems

- “Tripling renewable energy capacity” by 2030

- “Doubling the global average annual rate of energy efficiency improvements” by 2030

- Mobilizing greater action to drive electric vehicle implementation and other low-carbon transportation systems

- Accelerating greater action from non-CO2 gases, in particular methane

- “Enhanced efforts towards halting and reversing deforestation and forest degradation by 2030”

Agreeing to Phase-Out Fossil Fuels and Ramp-up Clean Energy

To deliver on our 1.5°C goals, the world needs to rapidly phase-down fossil fuel production and consumption, ramp up clean energy, and decrease the emissions associated with these activities. At COP28 we witnessed some important new efforts to deliver on these objectives.

Committing to a just and equitable fossil fuel phase-out. Leading countries, advocates, companies, and scientists sent a clear message at COP28 that we need to rally around an “orderly phase out of all fossil fuels in a just & equitable way, in line with a 1.5C trajectory”. While the final negotiated agreement included weakened language from what leaders were pushing, the signal is clear that the end of the fossil fuel era has begun. This is evident in the fact that a phase-out was called for by the vast majority of countries with more than 140 countries publicly stating that position, more than 200 leading companies calling for it, more than 2,000 leaders from around the world making a public push at COP28, and calls from the Pope.

At COP28, we witnessed some growing signs of near-term action to shift away from fossil fuels. Australia and Norway joined the group of countries committing to end overseas public financing of fossil fuel projects through the Clean Energy Transition Partnership (CETP). The Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance (BOGA) both announcing new member countries and issuing a call to action to have a “peak in fossil fuel production and consumption this decade”.

Much work lies ahead to translate these promises into action, with the need for key countries to rapidly shift away from fossil fuels in their production and consumption. This is evident in the UNEP Production Gap report showing that key countries are planning more fossil production than is consistent with a 1.5°C trajectory (see figure).

2021 extraction-based emissions from key countries

Ramp-up renewable energy and doubling energy efficiency. As a part of the final COP28 outcome, world leaders endorsed a global goal of at least tripling global renewables capacity and doubling energy efficiency by 2030. By the close of COP28, 130 countries had endorsed the Global Renewables and Energy Efficiency Pledge. The signatory countries agreed with the International Energy Agency and the International Renewable Energy Agency forecast that, to limit warming to 1.5°C, the world requires 3 times more renewable energy capacity to be installed by 2030, or at least 11,000 GW, and must double the global average annual rate of energy efficiency improvements from around 2 percent to over 4 percent every year until 2030. According to one analysis, delivering on this target would require “mobilizing approximately 1.5 GW of new wind and solar capacity additions per year” between 2024 and end of 2030.

Country national targets are already heading towards a doubling, but a step change will be required to reach the goal of three times renewable energy capacity by 2030, according to analysis from Ember (see figure). For the pledge to succeed, countries need to take coordinated and urgent action that delivers adequate finance, resolves permitting and grid related bottlenecks and builds resilient supply chains.

Pathway to tripling renewable energy capacity by 2030

There are emerging signs of progress towards delivering these goals, with over 400 companies having now committed to purchasing 100% renewable energy for their operations and more than 250 organizations prepared to push governments to deliver on the commitment to triple renewable energy and double energy efficiency. At COP28 leaders highlighted a particular need to ramp-up efforts in Africa when they recommitted to the Accelerated Partnership for Renewables in Africa (APRA) that was founded by Kenya, Ethiopia, Namibia, Rwanda, Sierra Leone and Zimbabwe, with support from Denmark, Germany, the UAE and the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). And after the climate summit, Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Luxemburg, the Netherlands and Switzerland announced they will jointly decarbonize their interconnected electricity system by 2035.

Addressing coal-fired power plants. This decade we need to also stop the construction of new coal-fired power plants without significant emissions controls and rapidly reduce emissions from existing coal power generation if the world is to keep the 1.5°C target alive. This need was recognized by 130 countries who stated that this decade we need: “…the phase down of unabated coal power, in particular ending the continued investment in unabated new coal-fired power plants…” While the COP28 outcome didn’t set a firm commitment on coal reductions this decade as a number of countries were calling for, the U.S., Czech Republic, Cyprus, Dominican Republic, Iceland, Kosovo, Norway, and the U.A.E. joined the Power Past Coal Alliance. This puts a spotlight on the other major coal users in the world.

While China leads the world in clean energy investment and utilization, it will need to combine these efforts with an accelerated shift away from coal power as the core of its power system to build a new energy system centered on renewables, and implement the goals it set in 2021 to “strictly control coal-fired power generation projects” and phase down coal consumption starting in the 15th Five Year Plan (2026-30).

Key decision-makers also furthered the implementation of efforts to retire coal plants early and decrease the emissions from the existing coal fleet. At COP28, Vietnam released their “Resource Mobilization Plan (RMP)”, which lays out the investment needs and plans to deliver on their Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP). The JETP commits to hold Viet Nam’s annual power sector emissions to 170 megatons CO2e by 2030, peak its coal-fired generation capacity at 30.2 GW, and increase renewable energy generation to 47 percent by 2030. Indonesia and the Asian Development Bank laid out further details on their agreement to retire 660 MW coal-fired power plant seven years early. Further details are expected next year on Indonesia’s plans to deliver on their JETP which commits to peak total on-grid power sector emissions to no more than 250 MT CO2, increase renewable energy generation share 44 percent, and control “captive coal plants”. These national-level efforts will be supported by progress on mobilizing finance to support the transition as recognized in initiatives like the Coal Transition Accelerator.

Aligning oil and gas with 1.5°C. To be on a 1.5°C pathway, global consumption of fossil gas needs to decline by around 20 percent from today’s levels by 2030 and be on a path to a over 75 percent cut by 2030, according to the International Energy Agency. The COP28 outcome sent a direction on oil and gas with countries committing to: “accelerating action in this critical decade, so as to achieve net zero by 2050 in keeping with the science”. That means that oil and gas demand and supply need to be on a clear path in 2030 to ZERO by 2050 as aligned with the science. This means that developed countries need to be on an accelerated path to zero emissions from fossil gas by around 2040, with a 80 percent emissions decline in developed countries and a 60 percent decrease in emerging economies by 2030. And it means developed countries need to stop the expansion of fossil gas infrastructure, today.

Before and at COP28, there were increasing efforts to control methane including from oil and gas operations. The U.S. EPA announced final oil and gas methane rules to control domestic methane emissions, the European Parliament and the Council reached a provisional agreement to control methane emissions from domestic sources and imported fossil gas, Canada proposed new standards to reduce methane pollution from the oil and gas industry to reduce methane emissions from the sector by more than 75 percent by 2030, and more countries joined the Global Methane Pledge. Governments, philanthropies, and the private sector announced over $1 billion in new funding for methane reduction as part of the Methane Finance Sprint to support developing countries in reducing methane emissions. As we noted: “Spurring industry and others to invest in cleaning up methane venting and flaring in developing countries pays multiple dividends”. While the Oil and Gas Decarbonization Charter (OGDC)promoting actions to reduce the industry’s emissions was signed by 50 companies, it didn’t include several major oil and gas companies like – Chevron and ConocoPhillips or National Oil Companies – and didn’t include actions to reduce emissions from the vast majority of the industries emissions.

Greater action will be needed from major oil and fossil gas producers to align action with the commitments from COP28. For the U.S. this means: “immediately reining in the massive climate and equity impacts of liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports and infrastructure, ending wasteful taxpayer handouts for coal, gas and oil, and halting the expansion of fossil fuel production on public lands and in federal oceans”. The evidence behind liquified natural gas (LNG) as a climate solution continues to collapse with NRDC research showing that clean energy beats LNG, LNG has a number of risky realities, and that LNG facilities are a bad investment.

Delivering on the promise of COP28 means no new oil and gas development is needed, and even some existing projects will be retired before the end of their planned life cycle.

Mobilizing for better cooling. Based on current policies, the installed capacity of cooling equipment will triple, resulting in a more than doubling of electricity consumption, and an increase in cooling emissions to 6.1 billion CO2e in 2050, according to the first Global Cooling Watch 2023 report. This challenge received major new and much needed attention at COP28 when 66 countries and leading companies and other groups signed the Global Cooling Pledge, including committing to:

- reducing cooling-related emissions across all sectors by at least 68% globally relative to 2022 levels by 2050,

- ratifying the Kigali Amendment by 2024,

- publishing a national cooling action plan,

- establishing national building energy codes by 2030 that incorporate cooling strategies,

- take steps to increase the global average efficiency rating of new air conditioning equipment sold by 50% by at the latest 2030 from global 2022 installed baseline,

- establish Minimum Energy Performance Standards (MEPS) by at the latest 2030,

- establish public procurement policies and guidance for low-GWP and high efficiency cooling technologies at the latest by 2030, and

- pursue the life cycle management of fluorocarbons in particular addressing HFCs banks.

In an increasingly warming world, cooling is no longer a luxury but a tool for survival. This commitment will help to deliver more cooling with less warming. The air conditioners we use, the refrigerators that keep our food cold, and the way we build our buildings is in desperate need of a revamp. The cooling challenge is also an opportunity to build smart from the start, especially in the countries of the global south, where the infrastructure required for cooling is yet to be built. The global watch report also presents a modeled pathway to get to “near-zero” emissions for the sector, which shows cooling-related emissions by 2050 could be cut by over 60% compared to business-as-usual while expanding cooling access to 3.5 billion people.

As a result, COP28 was the coolest COP to date.

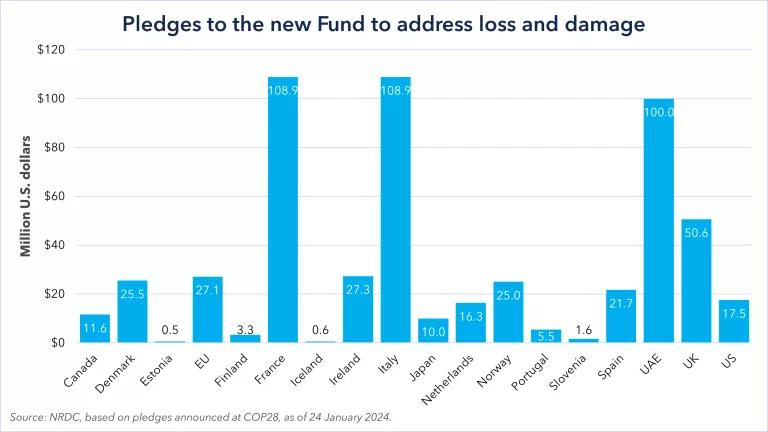

Setting up the Loss and Damage Fund

At COP28, governments formalized the details of a Fund governments agreed to create at COP27 to assist vulnerable developing countries in responding to loss and damage from climate change. The Fund was established in record time and resourced at a record pace. This was an historic achievement. All wealthy and high-emitting countries now have a responsibility to step up and contribute to the Fund.

Approving the loss and damage Fund’s governing instrument and mobilizing pledges. Throughout 2023, a Transitional Committee comprised of governments representing all regions of the world met to develop consensus recommendations for the operationalization of the Fund. The recommended governing instrument, which sets out the structure and operational details of the Fund was adopted on the first day of COP28 – unprecedented, as formal decisions are typically only taken on the last day of the COP.

The governing instrument establishes the Fund with a mandate to: support particularly vulnerable developing countries; have a streamlined and rapid approval process; disburse funding through a variety of channels, including to direct budget support to national governments; use a variety of financial instruments including grants and highly concessional finance; and initially be hosted by the World Bank, but with an option to move it elsewhere at a later date.

Following the formalization of the fund, within minutes several rich countries announced initial contributions to the loss and damage fund. The COP Presidency, the United Arab Emirates, and Germany kicked off the pledges with $100 million each. France and Italy announced the joint largest pledges to the Fund, €100 million ($109 million) each. The United States pledged $17.5 million. By the close of COP, total pledges to the loss and damage fund totaled $655.9 million (see graph).

Keep track of pledges to the loss and damage fund at NRDC’s COP28 Climate Fund Pledge Tracker.

Joe Thwaites/NRDC

These early pledges are very welcome. Previous UN climate funds have taken years between their creation and significant pledges from governments. Such early pledges are unprecedented and indicate a desire to get the fund operating as soon as possible.

Governments have been asked to nominate members for the Fund’s Board as soon as possible. The Board is due to hold its first meeting before the end of January 2024. In addition to agreeing key policies to allow the Fund to start approving funding rapidly, the Board will need to decide the name of the Fund. One idea which enjoys widespread support is to name the Fund after the late scientist Saleemul Huq, a tireless advocate for the Fund’s creation.

To play its part in meeting developing countries’ loss and damage funding needs, which are estimated to already run into the hundreds of billions of dollars per year, it is clear the Fund will need more resources. Developed countries that have yet to pledge to the new Fund – such as Austria, Belgium, and Sweden – should step up and do so. Other developed countries that pledged only modest amounts should work to increase their contributions. Following UAE’s lead, other rich and high-emitting countries that are significant contributors to the climate crisis and have significant capacity to provide support, such as Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Kuwait should also step up and contribute.

Companies, philanthropies and other non-state actors, including individuals, can also contribute to the Fund, and a key thing to watch in coming months is whether any of these entities will do so. Highly polluting industries, particularly fossil fuel companies, ought to be footing the bill for the loss and damage they are causing. If these industries don’t contribute to the Fund voluntarily, governments should explore ways to compel them to. This is where the Fund’s ability to accept “innovative sources” of funding can play an important role. Such sources could include windfall taxes on fossil fuel profits, levies on the shipping industry’s emissions, and surcharges on first and business class flights. These kinds of mechanisms are already being used by many governments, just not yet with revenues directed towards climate action.

Mobilizing the full suite of sources of loss and damage finance. Countries need to mobilize funding through a variety of mechanisms. In addition to pledges to the new Fund, governments announced over $130 million for other institutions and initiatives that support loss and damage. There are several other ways governments can free up resources for loss and damage. For example, developing countries have significant debt challenges tied to climate impacts that can be addressed through debt relief measures. And other existing funding mechanisms must be better equipped and if necessary adapted to effectively address loss and damage. While COP28 didn’t make major breakthroughs on these reforms, countries recognized the need to address “fiscal space” – i.e., that failure to address sovereign debt crises and find sustainable sources of revenues will stymie climate action.

Mobilizing More Climate Finance

In 2022, total global climate finance reached a record $1.4 trillion, but needs to reach over $5 trillion per year by 2030, an increase of half a trillion per year for the rest of this decade. The COP28 outcome recognizes the need to scale-up finance and made some limited progress to rapidly increasing the needed resources.

Over the past year, there has been a growing focus on mobilizing the variety of public, private, and innovative sources of finance to help drive greater climate action. The need to mobilize these various sources was reflected in a “Leaders Declaration on a Global Climate Finance Framework” signed at COP28 by 13 countries, including five G20 members alongside key developing countries that have been championing reforms to the financial system to advance climate action, such as Barbados, Colombia and Kenya. A key test for the longevity of this framework will be whether it attracts more country endorsements and develops a tangible plan of action to implement the principles, or quietly fades away, as has been the case for many initiatives launched by previous COP presidencies.

Scaling up needed climate finance will require progress on several key aspects over the coming year.

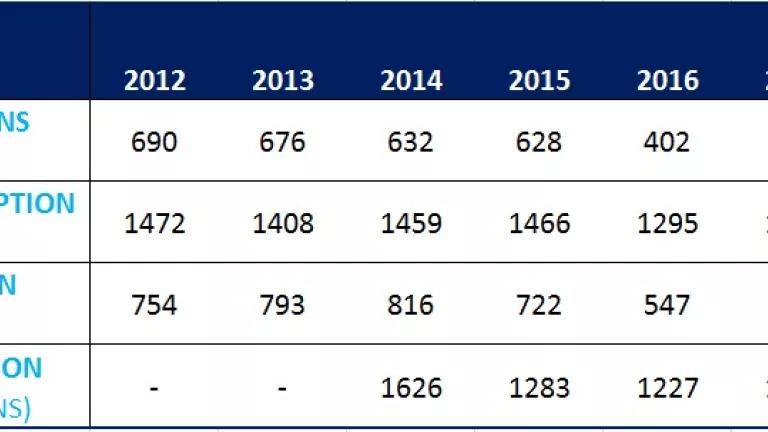

Delivering on the $100 billion per year target. The latest published data for 2021 shows developed countries still fell $10.4 billion short of meeting the $100 billion pledge that they committed to deliver by 2020. Developed countries provided assurances that they have finally delivered on this commitment, with the OECD saying that based on preliminary but unverified data, they expect the goal will be met in 2022. Recent reporting by MDBs, European Union, and the U.S. showing increases in their 2022 climate finance adds confidence to this projection, but the onus remains on all developed countries to report their climate finance data transparently so that the OECD, UNFCCC and other analysts can conduct their own accounting.

Even once developed countries have meet the $100 billion commitment, they should aim to exceed this level in 2023, 2024 and 2025, to make up for the $27 billion shortfall in 2020 and 2021 and ensure their contributions across the period 2020 to 2025 average at least $100 billion a year.

Doubling adaptation finance. Developed countries committed to at least double their adaptation finance from 2019 levels by 2025, which would result in an increase from $20 billion to $40 billion. The OECD found that adaptation finance fell by $4 billion in 2021 to $24.6 billion, 27% of total climate finance from developed countries.

The need to increase adaptation support was recognized in the philanthropy call to action on adaptation and the Race to Resilience progress report. Much more work needs to be done to rapidly scale-up adaptation support as the costs of adaptation continue to rise, as documented in the UNEP Adaptation Gap report, which found that adaption costs have risen to $215-387 billion per year this decade, more than 50 percent higher than previous estimates.

A key way developed countries can provide reassurance that they are working to get adaptation funding back on track is to make new pledges to multilateral adaptation-focused funds such as the Adaptation Fund, Least Developed Countries Fund (LDCF), Special Climate Change Fund (SCCF), as well as the Green Climate Fund, which directs half of its funding to adaptation projects. They have proven track records in rapidly delivering grant-based funding to vulnerable countries. At COP28, the Adaptation Fund received new pledges of $191.7 million from 14 countries, unfortunately short of the $233 million raised last year and the $300 million the Board set as a 2023 fundraising target. The LDCF received $144.4 million in new pledges from seven countries, more than double the $70 million pledged last year, and the SCCF secured $34.9 million in new pledges from four countries, almost matching the $35.1 million pledged at COP27 (see figure).

Keep track of pledges to these funds at NRDC’s COP28 Climate Fund Pledge Tracker.

Joe Thwaites/NRDC

Replenishing the Green Climate Fund. The Green Climate Fund (GCF) is the world’s largest multilateral fund dedicated to helping developing countries address the climate crisis. With $3.5 billion in new pledges announced at COP28, the GCF’s second replenishment now stands at $12.8 billion, far exceeding the $10 billion raised in each of the two previous fundraising rounds (see figure).

After not contributing to the first GCF replenishment, at COP28 Vice President Kamala Harris announced the U.S. would recommit to the GCF with another $3 billion pledge. “The Biden administration must now work with Congress to swiftly turn its pledges into real dollars – there’s not a moment to lose”, as NRDC’s CEO and President stated. Other rich, high-emitting countries are under increasing pressure to step up and pledge to the GCF. They would join ten other emerging economies, including South Korea, Mexico, and Colombia, that have previously contributed.

Keep track of all the GCF contribution announcements at NRDC’s Green Climate Fund Pledge Tracker.

Joe Thwaites/NRDC

Preparing for the post-2025 climate finance goal. When adopting the Paris Agreement in 2015, governments also agreed to set a new collective quantified finance goal for the post-2025 period “from a floor of $100 billion per year.” The new goal is to be decided at COP29 next year and is a critical commitment for providing reassurance to developing countries that there will be sufficient support needed for them to ramp up their climate action. At COP28 governments agreed to hold additional meetings throughout 2024 to begin work on a draft negotiating text. Alongside the overall scale of the new goal, perhaps the thorniest question is which countries should contribute. With a growing number of other countries now having wealth and greenhouse gas emissions higher than many developed countries, a growing body of analytical work suggests that an equitable approach to climate finance goals would entail these additional countries also taking on responsibility to contribute. The extra meetings in 2024 provide space for governments to grapple with these difficult questions and begin working on the text of the final decision, so that when they arrive at COP29 next November they will not be staring at a blank sheet of paper.

Reforming the International Financial Institutions. With the renewed focus on how to reform international financial institutions, including the multilateral development banks (MDBs) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the COP28 decision called for shareholders in these institutions to continue reforms to better scale up climate finance.

As they have done at recent COPs, the MDBs released a joint statement announcing efforts to: support country-led climate and development platforms to help coordinate action, enhance support for disaster risk management and building of resilience, better integrate climate analytics into their country support, launch a new joint MDB program to support countries to formulate Long-Term Strategies encouraged by the Paris Agreement, and implement “MDB Common Principles for Tracking Nature-Positive Finance” (alongside their commitment to align all their investments with the Paris Agreement’s goals).

While the joint statement was lacking in quantified commitments, individual MDBs did also announce new financing:

- The World Bank Group (WBG) committed to increase its target for the share of total financing going to climate-related projects from 35% to 45% by 2025, which equates to an additional $9 billion in climate finance per year.

- World Bank President Ajay Banga also pledged $5bn to support 100 million people in Africa with clean energy access over the next seven years.

- The Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) announced a tripling of its climate finance over the next decade, equivalent to $15 billion a year.

- The IDB also announced an additional $5 billion over the next decade for sustainable development projects in the Amazon.

- The Islamic Development Bank announced $1bn to support adaptation in conflict affected countries.

- The African Development Bank (AfDC) announced a $1 billion facility to provide insurance against climate impacts for over 40 million farmers across Africa.

Unfortunately, days after COP28 ended, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) finalized an energy sector lending strategy that still leaves open the possibility it will invest in climate-misaligned fossil fuel projects.

The IMF announced after COP that it will temporarily raise the caps to its concessional finance for low-income countries. There was also progress on using Special Drawing Rights” (SDRs) at the African Development Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank, with key countries and the IMF signaling they are ready to formalize this use of SDRs.

Dealing with debt. COP28 also saw some progress on addressing the debt crisis which is stifling the ability of the most vulnerable countries to invest in climate strategies. After first being announced at the Paris Summit for a New Global Financial Pact in June this year, COP28 saw the formal launch of the Global Expert Review on Debt, Nature and Climate. Led by Presidents Macron of France, Petro of Colombia and Ruto of Kenya, the review will bring together leading experts to independently examine how sovereign debt hinders climate ambition, and explore solutions to this.

A group of MDBs, climate funds and development finance institutions launched the Joint Declaration and Task Force on Credit Enhancement of Sustainability-Linked Sovereign Financing for Nature and Climate. The initiative aims to provide credit enhancement for climate- and nature-linked sovereign financing, such as guarantees and insurance. Key players in the insurance and reinsurance industry have signaled support for the initiative.

The World Bank announced it would extend their “debt pause clauses” for extreme weather events to also include not only the principal repayments but also debt interest payments.

Much greater action on resolving the debt crisis will be needed this year.

Innovative sources of finance. Another initiative to arise from the June 2023 Paris summit, the Taskforce on International Taxation, was also launched at COP28. Endorsed by Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, France, Kenya and Spain, the Taskforce will evaluate innovative taxation ideas such as taxes on fossil fuels, shipping, and aviation, as well as financial transaction taxes, and agree on specific proposals for raising additional climate finance for adoption by relevant institutions at COP30. Many of these mechanisms are already being used to raise revenues for spending in other areas, so they have already proven some feasibility. Given the need for substantially increased grant-based and highly-concessional finance for climate action, and the political hurdles of increasing spending from government budgetary processes, the Taskforce is a promising initiative to raise money in a more equitable manner by focusing the tax burden on the most polluting industries and individuals.

More big finance pledges, too good to be true? There were also a number of new multi-billion dollar climate finance announcements, including:

- The UAE announced the launch of a $30 billion Alterra fund, which will invest in climate projects around the world. This will primarily be profit-seeking investment, with only $5 billion in concessional finance focused on developing countries.

- The Allied Climate Partners (ACP) platform was launched, which will pool $825 million in capital from philanthropic foundations, MDBs and DFIs and aims use this to leverage $11 billion for investment in climate projects in developing countries. This target equates to $14 mobilized for every $1 of capital provided by the platform, extremely ambitious given that MDBs and developed countries are currently mobilizing just cents in private finance for every dollar of public funding they provide.

If these commitments materialize as promised, they could certainly help shift the needle in scaling climate finance, but given the history of big commitments that quickly crumble under scrutiny, the onus is on those announcing pledges to be clear about the details so they can be held accountable for delivery.

Protecting Forests

At COP26 in 2021, more than 140 countries signed the Glasgow Leaders' Declaration on Forests and Land Use, committing to halting and reversing worldwide deforestation and land degradation by 2030. At COP28, all 194 countries that are Parties to the Paris Agreement reinforced this commitment with a decision text that: “further emphasizes the importance of conserving, protecting and restoring nature and ecosystems towards achieving the Paris Agreement temperature goal, including through enhanced efforts towards halting and reversing deforestation and forest degradation by 2030”.

The renewal of the Glasgow commitment comes at a critical moment as, over the past two years, there have been significant warning signs that countries are not positioned to deliver on their promise, either in the tropics or in northern forests. In 2022, the loss of tropical primary forests increased, while degradation in northern forests continued essentially unabated, with devastating consequences for climate and biodiversity.

This lack of progress led African ministers and more than 100 organizations to call for countries to establish a Glasgow Declaration Accountability Framework (GDAF). The GDAF would drive government-led transparency, facilitate policy and finance commitments, and foster alignment, positioning the international community to deliver equitably on the transformative change it pledged in Dubai.

Fortunately, COP28 set reaffirmed and elevated expectations for progress, launching groundbreaking efforts and commitments to help protect northern and tropical forests, while recognizing the need for synergistic solutions to the intertwined climate and biodiversity crises.

If paired with the establishment of a GDAF, these developments can spur a course-correction on forest protection, putting the international community on track to meet its 2030 targets.

A clearcut in Quebec, which is not considered deforestation.

Mobilizing action in northern forests. Longstanding policy inequities have allowed the Global North to call for action from tropical countries while sidestepping accountability for the industrial logging in their own forests, which constitutes the single largest driver of tree cover loss in the world. Canada, for example, can claim near-zero deforestation despite clearcutting more than 550,000 hectares of forests annually. A recent study found that this logging has severely degraded two of Canada’s provinces. This loss of high-integrity forests, and their unique value, however, is erased from the ledger books.

Through carving out protections for their own industrial logging, northern countries have hampered forest protection efforts everywhere. The COP28 outcome leaves no ambiguity as Jennifer Skene of NRDC stated:

“The emphasis on halting and reversing forest degradation, alongside deforestation, by 2030 leaves no ambiguity about the urgency of global, multisectoral action to protect high-integrity forests in order to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement. The international community is stripping away the veil over industrial logging in northern forests and its significant emissions, creating a pathway for action on forest protection defined by equity and accountability."

Delivering on COP28’s prioritization of halting both deforestation and forest degradation requires alignment around standards that apply to both the Global North and the Global South. Through establishing a GDAF, countries can foster common, equitable action tailored to ecological exigencies rather than geopolitical dynamics.

Addressing the true climate impact of deforestation and forest degradation also necessitates long-overdue reforms of forest carbon accounting practices to transparently and accurately reflect the logging industry’s impact. A recent study estimates that logging, much of which occurs in northern forests, will contribute 3.5 to 4.2 billion metric tons of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere annually over the coming decades, an amount equivalent to approximately 10 percent of recent annual global emissions. This dynamic is evident in Canada where, according to a report from NRDC and Nature Canada, the Government of Canada’s own data shows the country’s logging industry is responsible for more than 10% of Canada’s total annual greenhouse gas emissions. Yet Canada, using biased accounting practices, represents the forestry sector, and the erosion of uniquely carbon-dense forests, as a net-zero industry.

Following COP28, the United States added to the chorus of policymaking and marketplace momentum that is stripping away the fiction about the renewability of northern forests. The Biden Administration proposed a nationwide forest plan amendment focused on protecting federal old-growth forests, making progress toward delivering on advocacy from a coalition of more than 120 groups for rules that would protect mature and old-growth trees and forests from logging. As NRDC’s Andrew Wetzler stated: "This is a key step in making mature and old-growth trees and forests into a centerpiece of our national efforts to combat the climate crisis and preserve our national natural heritage”. It also provides a new model for global policy.

Driving action in the Tropics. At COP28, some countries and investors mobilized additional resources to support tropical countries in halting deforestation and forest degradation by 2030. This builds upon the $5.7 billion in finance that was mobilized in 2022 towards the five year goal of $12 billion set at COP26. The Forest and Climate Leaders’ Partnership announced new “country packages” that create national plans combining public, private, and civil society financing. These include: in Ghana $30 million (plus an additional $50 million from the voluntary carbon market LEAF program), Papua New Guinea with $100 million, Republic of Congo with $50m, and Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) with $62 million. In addition, Columbia announced a plan for enhancing national ambition through strengthening governance, peace-building, and sustainable development. The Amazon Fund – created by Brazil to support efforts to halt deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon – witnessed some additional contributions from Norway ($50 million), France ($550 million over 3 years), and the UK ($38 million in addition to the $90 million they announced in May). The meeting also saw Brazil launch a call for the creation of a “Tropical Forest Forever” fund with an aim to raise $250 billion and some additional actions from Brazil to meet its goal of zero deforestation by 2030. And Norway announced an additional $100 million to Indonesia for its deforestation reduction efforts and signaled it will continue to support global deforestation efforts with $375 million in 2024.

The MDBs also highlighted a new urgency to finance nature-based solutions in the key regions they operate. The Asian Development Bank launched a Nature Solutions Finance Hub for Asia and the Pacific with an aim to attract at least US$2 billion in investment programs that incorporate nature-based solutions, with a focus on capital markets. The Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) announced that they are committing an additional $5 billion by 2030 to sustainable development projects in the Amazon Region as a part of the IDB’s Amazonia Forever program.

Cleaning up the commodity supply-chain. In addition to addressing their own domestic forest impacts, Global North countries, along with companies, need to develop standards and tools curbing the impacts of their trade on driving deforestation and degradation abroad. Coinciding with COP28, several companies and countries made new commitments on supply-chains:

- Cargill – a major purchaser of deforestation-driving products – has committed to eliminate ecosystem destruction linked to key commodities in Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay by 2025.

- Through the Nature Positive for Climate Action campaign companies are integrating nature into climate transition plans including asset manager RobecoSAM who has launched specific biodiversity investment strategies and Unilever that is embedding nature into its transition plans, with plans to achieve deforestation-free supply chains for five commodities.

- The UK announced the next steps in implementing its rules to ban the sale of products with illegal deforestation in their supply chains by highlighting the regulations would apply to palm oil, cocoa, beef, leather and soya.

Integrating climate and biodiversity goals. COP28 also ushered in the era of joint, synergistic action to address climate change and biodiversity collapse as inextricably linked crises. More than 15 countries, including China, the United States, Brazil, Canada, Brazil, and Colombia, signed a new Joint Statement on Climate, Nature, and People that commits to aligning and integrating climate and biodiversity targets and plans. The Joint Statement brings the targets and principles of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (KMGBF), finalized last year, into the climate fold. From there, the KMGBF found its way into the Global Stocktake, calcifying the link between the historically bifurcated UN biodiversity and climate conventions.

For forests, the KMBGF’s integration is a meaningful step toward turning platitudes and latitudes into concrete, rigorous action. Action on forests has, for years, vacillated between exculpatory tree planting pledges and real commitments, like the Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration, that focus on nature protection as the most effective, immediate means of preserving ecosystems’ value for the climate. Foregrounding ecological integrity as its own metric of climate ambition makes clear that there is no substitute for protecting the forests we have left.

Decarbonizing Industry

Reducing emissions from heavy industries such as cement, iron and steel, aluminum, and petrochemicals is an emerging new component of the global architecture with additional announcements at COP28.

Hydrogen. While offering a promising potential to support the energy transition by replacing fossil fuels in the hardest to electrify sectors of the economy, hydrogen also carries significant risks. If not carefully deployed and subject to rigorous guardrails, it risks hindering the clean energy transition and increasing its costs. Absent strong standards, hydrogen production can be very carbon intensive; and if hydrogen deployment is not targeted to hard-to-electrify applications, it may cannibalize more efficient clean energy solutions (notably, direct electrification) and stall the clean energy transition. So, enacting effective and rigorous guardrails is critical to harvest hydrogen’s best potential and minimize its risks. At COP28, there was emerging signs of alignment on strong safeguards, with some problematic proposals from industry associations.

The UN high level climate champions launched a joint agreement on responsible deployment of renewables-based hydrogen. NRDC, along with other organizations, endorsed the agreement. This agreement sets some clear benchmarks to help ensure that hydrogen is scaled in a way that aligns with climate targets. In contrast, the technical specification proposed by the International Standards Organization (ISO) at COP28 lacked any specific threshold for what should be counted as “clean hydrogen”, alongside some other methodological issues which could strengthen the specification if resolved. Countries are beginning to recognize the need for clear and inter-operable standards, with over three dozen countries, including the U.S., France, Germany, India UAE, signing onto a declaration around “Mutual Recognition of Certification Schemes for Renewable and Low-Carbon Hydrogen and Hydrogen Derivatives”. After COP28, the Biden-Harris administration proposed new rules to implement the hydrogen tax credits in the Inflation Reduction Action that contain strong measures to turbocharge the U.S. hydrogen market and ensure that the “clean hydrogen industry grows while actually reducing emissions”. We also saw some emerging new buyers of green hydrogen with 30 leaders from the shipping sector signing a joint commitment with specific targets for the use of renewable hydrogen-derived shipping fuel this decade.

Delivering transformations in cement, steel, and aluminum. Industrial materials are foundational to everyday life and will be critical for the transition to a clean economy. However, the production of materials like cement, steel, and aluminum is highly emission intensive. Addressing these challenges will require an equitable transition that prioritizes frontline communities worldwide. Key players announced some important new steps at COP28 around cement, steel, and aluminum.

Several new platforms were launched to accelerate action in the industrial sector. A new “Industrial Transition Accelerator” was announced to support company and financing efforts for cement and steel, while Boeing, Tesla and GM committed to use Climate Trace data to decarbonize their steel and aluminum suppliers. The “Climate Club” was formally launched by 36 countriesto help developing countries reduce industrial emissions, while leading African countries announced an Africa Green Industrialization Initiative to attract finance and investment opportunities support low-carbon industrial efforts in the continent.

COP28 also saw some existing industrial sector platforms announce further progress. The First Movers coalition – where companies commit to specific purchase commitments in such sectors as aluminum, cement, and steel – grew to 95 private sector members. The Alliance for Alliance for Industry Decarbonization announced that leading companies have committed to specific actions that will cut their emissions by over 50 percent by 2030. And, Canada, Germany, U.K., and U.S. announced that they will adopt specific commitments to reduce emissions from the steel, cement and concrete that their governments purchase.

Climate-Smart Food and Agriculture

Our global food system is a top emitter of greenhouse gases, and 8-10% of the world’s emissions come from food loss and waste (FLW) across the food supply chain alone. So it was welcome news that COP28, for the first time ever, featured a distinct theme of Food and Agriculture Systems. With this focus, we saw some progress around food waste and transforming the food systems.

Food waste. Several inspiring announcements were made related to food loss and waste at COP28:

- The U.S. launched the draft National Strategy for Reducing Food Loss and Waste and Recycling Organics. The strategy spans three agencies – EPA, FDA, and USDA – and outlines the actions the agencies will take to help the U.S. meet its national goal of halving food waste by 2030.

- A new report – “Reducing Food Loss and Waste – A Roadmap for Philanthropy” –outlined $300 million-worth of global food waste reduction projects ripe for funding. The report was funded by Bezos Earth Fund, IKEA Foundation, Betsy and Jesse Fink Family Foundation, and Robertson Foundation.

- The UN Food & Agriculture Organization (FAO) published a roadmap outlining priorities for changing global food systems to achieve the 1.5°C. This global roadmap identifies ten priority areas, including food loss and waste, crops, and ensuring healthy diets for all.

- WasteMAP, a new tool to track and reduce waste methane emissions from landfills across the world, was unveiled by RMI, Clean Air Task Force (CATF), and Global Methane Hub. This also includes a decision-making tool for policymakers and/or other waste decision makers allowing them to optimize for better waste management practices.

- World Wildlife Fund and ReFED launched the U.S. Food Waste Pact, a national voluntary agreement that aims to help food businesses target waste reduction strategies, measure data and processes, and act on solutions to reduce food loss and waste in their work. Inaugural signatories include: Ahold Delhaize USA, ALDI USA, Aramark, Compass Group USA, Sodexo, Walmart, and Whole Foods Market, among others.

Transforming food systems. With the focus on food and agriculture, COP28 also witnessed some emerging platforms to advance actions across key aspects of the food system including:

- Almost 160 countries signing onto the COP28 Declaration on Sustainable Agriculture, Resilient Food Systems, and Climate Action.

- Over 200 non-state actors issuing a Call to Action for Transforming Food Systems for People, Nature, and Climate to “transform food and agriculture to become a key solution – not a leading driver – of the climate, nature and food crises”.

- The Alliance of Champions for Food Systems Transformation (ACF) was launched by Brazil, Cambodia, Norway, Rwanda, and Sierra Leone. This initiative aims to have countries adopt ten priority actions, update their NDCs by 2025 in line with these transformations, and annually report on progress.

- CIGAR secured more than $890 million to support smallholder farmers in low- and middle-income nations to develop more sustainable and equitable food systems, reduce farming emissions, and increase access to nutritious and healthy foods

- Six big dairy companies committed to report on and reduce methane through the Dairy Methane Action Alliance. To capture the bulk of the dairy market, some of the biggest dairy companies must also commit.

- The Bezos Earth Fund committed $57 million for food, with $30 million going towards reducing methane emissions from livestock.

Transportation

With transportation accounting for over 20 percent of global emissions and 60 percent of oil consumption, delivering greater progress to decarbonize transportation is an essential element of putting the world on a 1.5°C pathway and delivering on the commitments to phase-out fossil fuels. The COP26 climate summit had a specific focus on transportation with 31 national jurisdictions, 6 major automakers, and numerous subnational governments and companies announcing commitments to reach a 100 percent zero-emission vehicle sales goals. At COP28, there was some limited progress on transportation sector strategies:

- A leading transportation coalition issued a call to action to “double the share of energy efficient and fossil-free forms of land transport for people and goods by 2030”. The call currently has over 60 supporters from companies, governments, to NGOs.

- Analysis from the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT) prior to COP28 highlighted the progress of car manufacturers towards electric vehicle (EV) goals. They found that if manufacturers meet their current goals, EVs sales in leading markets would be around 32 percent by 2030 and 57 percent by 2035. A more optimistic analysis from RMI found that EVs will “make up between 62% and 86% of global car sales by 2030”. This is important progress, but short of COP26 commitments on EVs.

- 10 companies joined the Cargo Owners for Zero Emission Vessels at COP28, bringing the total to over 35 freight buyers working to drive ambition and action toward zero-emissions ocean transport. At COP28, this alliance also launched the Zero Emission Maritime Buyers Alliance (ZEMBA) to collaborate on demand aggregation and forward procurement of low emissions cargo transport.

- 12 more countries joined the Net Zero Government Initiative, increasing the total countries to 30 that have committed to put their national government operations on a path to reach net zero emissions by 2050. With transportation a significant source of the emissions from government operations, this commitment will steer government investments towards zero emission transportation options.

- The response to the Global Stocktake included transportation and EVs in a COP decision for the first time. It will be important for countries to formalize more specific transportation sector targets like the energy targets adopted at COP28.

Cities and States/Provinces

Cities and states/provinces play a critical role in several key strategies around climate change, so COP28 held the first ever “Local Climate Action Summit”, with COP28 culminating in:

- The launch of the Coalition for High Ambition Multi-Level Partnership, with endorsement from 71 countries. The coalition commits to support subnational government action and integrate that action into country NDCs. The initiative was paired with a $67 million new commitment from Bloomberg Philanthropies to continue their support of local climate action.

- Over 1,162 cities have now signed up to the Race to Zero campaign and set science-aligned targets for net zero emissions by 2050. Since 2021, the number of cities with such a commitment have increased by 52 percent.

Climate Health

COP28 also put a spotlight on the health implications of climate change with a dedicated “health day” during the summit. With this focus, 143 countries signed the Declaration on Climate and Health with a commitment to address the “interactions between human health and wellbeing” as a part of the international climate agreements. This was coupled with Guiding Principles for Financing Climate and Health Solutions developed by leading organizations setting out how financing institutions can deliver on this health and climate change focus. Several leading financing institutions announced funding to support efforts to prepare health systems for climate change and scale-up climate and health solutions.

More Emissions Cutting Action Urgently Needed

While the various commitments, new actions, and implementation progress at COP28 will play a critical role in closing the emissions gap by 2030, much greater action is urgently needed. To deliver on the promise of the Paris Agreement – to pursue efforts “to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels” – countries, companies, investors, and decision-makers at all levels will need to deliver greater action across all key sectors of the economy. This is evident in analysis from Climate Action Tracker that shows that even with full implementation of the existing NDCs, delivery of the coalition commitments from COP26, and the COP28 declarations, there will still be a significant emissions gap in 2030 to be on 1.5°C consistent pathway (see figure).

Analysis of progress towards 1.5°C with COP26 & COP28 actions

This highlights the need for stronger 2030 NDCs, greater domestic actions, more key players joining the sectoral commitments, and even stronger 2035 NDCs when countries formalize their next targets in early 2025.

The COP28 agreement signals the beginning of the end of the fossil fuel era and the ingredients necessary to put the world on 1.5°C consistent pathway by 2030. But the clock is ticking and bolder action is required.

Written by: Jake Schmidt, Brendan Guy, Joe Thwaites, Shruti Shukla, Jennifer Skene, Prima Madan, Pete Budden, Yvette Cabrera, Rennie Jones (a former fellow with NRDC)