From Dams to DAPL, the Army Corps’ Culture of Disdain for Indigenous Communities Must End

The prophesied “Seventh Generation” is here—demanding justice for tribes and protecting what they have left.

One of the privileges of being a member of the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate tribe is that I can travel the world knowing that whatever happens to me out there, I have a place to call home. On rolling green hills in northeastern South Dakota, the Lake Traverse Reservation is somewhere I can always go to find a roof and a hot meal with family. My mother, another world traveler, and I call it our home base for when life chews you up and spits you out.

I also know the idea of home can’t be taken for granted. Tribal lands have been taken, redrawn, and resurfaced too many times over recent centuries. Indigenous youth learn the history of our people in bits and pieces; a generational trauma still freshly sliced. When is the right time to tell your child your trauma, much less the trauma of your people? It is by subjugation’s design that Indigenous history is fractured to the point where we start to wonder how we got here.

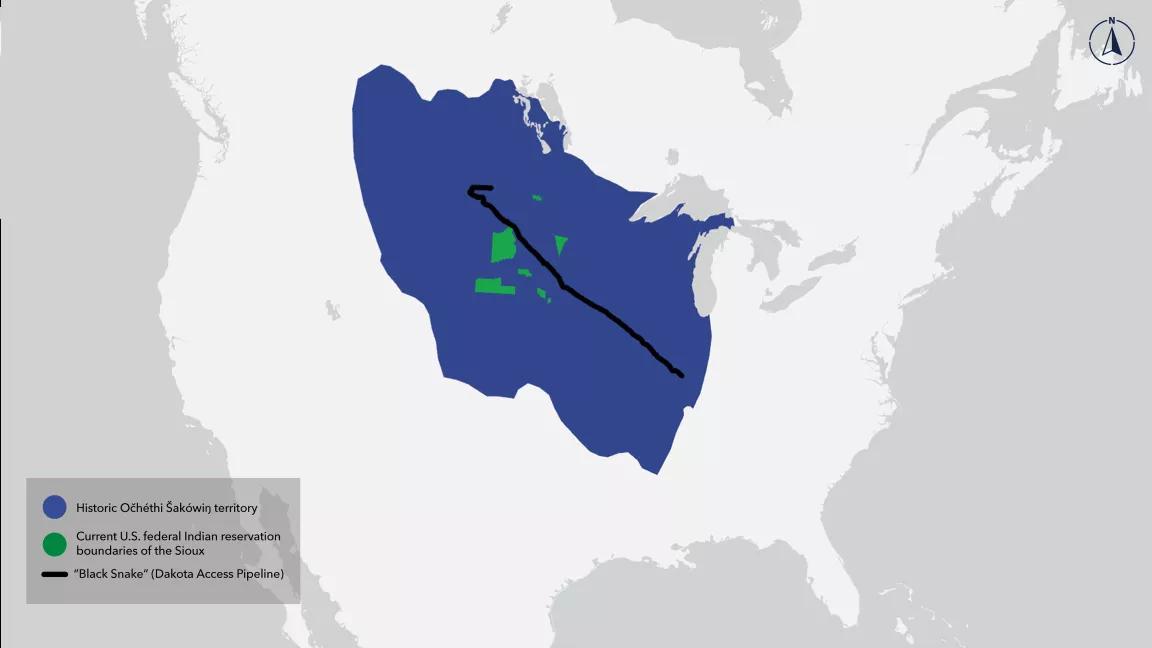

Until I joined the fight against the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL), I didn’t realize just how often the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (the Corps) had taken tribal lands in the Upper Midwest and beyond in order to build dams that flooded entire communities, transforming landscapes as well as lives. These are the wounds I didn’t know we had—wounds inflicted by deliberate calculations that deemed Indigenous communities expendable. Like a broken record, the betrayals of the federal government—the broken treaties, the broken promises, the broken trust—play over and over again.

Last week, the Corps released a draft environmental impact statement (EIS) that left open the possibility of DAPL continuing to shuttle Bakken crude oil beneath the Missouri River at Lake Oahe, the main water source for the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. “We’re furious that the Army Corps has addressed none of our major concerns during the review process,” wrote Janet Alkire, the tribe’s chairwoman, in a statement. Among the concerns are the dismal safety record of the pipeline operators, inadequate emergency response plans, conflicts of interests with the EIS preparation and the oil industry, and an overall lack of transparency that includes “inaccurate characterizations of tribal consultation.” Again, this behavior by the federal government is nothing new.

History (on repeat)

At the turn of the last century, the federal government forced many tribes along the Missouri River to move to reservations with arbitrary borders—like the one decades before that had separated families between the United States and Canada. The low river valley did, however, provide both cover from harsh winds and fertile soil, which helped in the adoption of a new farming lifestyle among those tribes. Yet within a few decades, many were forced to give up their homes again.

Approved by Congress in 1944, the Pick-Sloan plan within the Flood Control Act put the Corps, along with the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, in charge of constructing five major dams and reservoirs along the Missouri River, from Montana to Nebraska. Congress devised the plan as a way to prevent the river from flooding major cities, to provide irrigation for farmland, and to generate hydropower, but the benefits were to be enjoyed by predominantly European-American communities—at the cost of Indigenous ones. In too many cases, the Corps took tribal lands without consent via eminent domain to carry out Pick-Sloan. The Standing Rock Indian Reservation lost 87.5 square miles—an area more than triple the size of Manhattan—of the most fertile and productive land in South Dakota.

The Cheyenne River Reservation, which lies just south of Standing Rock, also saw huge losses. Some 60 years later, I am particularly struck by those who still post pictures to a social media group dedicated to the communities flooded by the Oahe Dam. The photos depict homes, schools, post offices, and gardens—now all entombed beneath hundreds of feet of water.

In his 2009 book Dammed Indians Revisited, historian Michael L. Lawson writes:

“The Oahe Dam destroyed more Indian land than any other single public works project in the United States. The Standing Rock and Cheyenne River Sioux lost a total of 160,889 acres [251 square miles]…including their most valuable rangeland, most of their gardens and cultivated farm tracts, and nearly all of their timber, wild fruit, and wildlife resources. The inundation of more than 105,000 acres [164 square miles] of choice grazing land affected 75 percent of the ranchers on the Cheyenne River Reservation.”

On top of the physical submersion of land and resources, the dams further destroyed Indigenous communities through the displacement of families and scattering of tribal members. In North Dakota, for instance, the floodwaters of the Garrison Dam, completed in 1953, split the Fort Berthold Reservation into five sections and displaced about 80 percent of the members of the Arikara, Hidatsa, and Mandan tribes. In all, Pick-Sloan resulted in the forcible takeover of 550 square miles of tribal lands, but the cumulative damage to Indigenous culture and society cannot be quantified.

The dams set tribes back from the progress they’d made since the creation of the reservations, and echoed their previous forced migrations. Because the Corps has a long history of condemning Indigenous communities through “negotiations” presented as faits accomplis, it’s hard not to see these actions as a coordinated attack on our people.

DAPL presents a similar scenario. The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and other members of the Great Plains Tribal Water Alliance (GPTWA) have spent years pushing for the Corps to complete an Environmental Impact Statement in order to ensure the pipeline’s owner, Energy Transfer LP, is held accountable. Since 2016, the GPTWA has fought for the most basic protections—the same protections afforded to predominantly white Bismarck, North Dakota, when the city’s concerns over DAPL contaminating its water supply led to the pipeline’s rerouting to Standing Rock.

A threat to water is a threat to life. The Standing Rock Sioux rely on Lake Oahe for drinking water and irrigation for their crops. The lake’s ecological health is crucial for subsistence hunting and fishing. Its shores host sweat lodge sites while the lake itself serves as a memorial to what the tribe lost to the Pick-Sloan plan, losses that ripple both below and above the water’s surface.

Water protectors march along a road in protest against plans to build the Dakota Access Pipeline near the Standing Rock Indian Reservation in North Dakota, on November 18, 2016.

Stephanie Keith/Reuters

The prophecy of the Seventh Generation

Over the history of the United States, the oppression and exploitation of Indigenous Peoples have been omnipresent. However, I am not without hope—especially when I consider the future envisioned by the Lakota holy man Black Elk.

As a young boy in the late 1800s, Black Elk prophesied that the seventh generation born since the first contact with Europeans would pull all the people of the world out of darkness. He shared his vision with leaders Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull, after which Crazy Horse announced, “Upon suffering beyond suffering, the red nation shall rise again, and it shall be a blessing for a sick world…I see a time of Seven Generations when all the colors of mankind will gather under the sacred tree of life, and the whole earth will become one circle again.”

The Indigenous youth of today are believed to be that prophesied generation. Now is the time for our healing journey to progress from treating our wounds to demanding justice. To become an activist means to understand how to care for my family and my community, and to protect the ecosystem for future generations. It’s something I learned from the elders—to keep safe what we have left. It is something I feel I just have to do.

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

The Dakota Access Pipeline threatens the water and welfare of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe.

Send a message to the U.S. Army Corps with the Lakota People's Law Project.

Tell the U.S. Army Corps to Shut Down the Dakota Access Pipeline

The Corps's draft environmental impact statement (EIS) leaves open the possibility of DAPL continuing to threaten the main water source for the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. Demand it issue a new and valid EIS.

The Dakota Access Pipeline: What You Need to Know

When Customers and Investors Demand Corporate Sustainability

How to Make an Effective Public Comment