Composting Is Way Easier Than You Think

With minimal effort, you can turn those banana peels and apple cores into gold. Let us break it down.

If you’re going to ask an environmentalist why you should compost, make sure you have a minute. Darby Hoover, NRDC’s senior resource specialist in the Food and Agriculture program—and master of the household compost heap—can reel off a long list of reasons for keeping your food scraps and other household waste out of the trash can. “Compost adds nutrients and organic matter back to soil, which benefits agriculture, reduces our reliance on synthetic fertilizers, diverts methane-producing organic materials from landfills, and improves soil’s water retention capacity so you don’t need to water as much,” she says.

Not sold yet? This controlled method of helping food decompose is also much easier (and less gross) than you think. Seriously. Just follow these six pointers.

Set up your space.

Food is going to rot, no matter what. All you have to do is help. “You don’t need a lot of technology,“ Hoover says. “You just want to make the food break down in a way that’s compatible with your life.” If you have room in your yard and the temperature where you live is even somewhat moderate, you can fence off an area (3 x 3 x 3 feet is considered ideal) and start your scrap pile directly on the ground. For a tidier arrangement, buy or make bins to contain your organic waste or drums that tumble and aerate it, which helps to convert it to compost even faster. See more details on the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s website. Even apartment dwellers can get in on the action: Indoor bins stocked with red worms, critters you can order online, process food scraps in a smaller space. (This NRDC Tumblr post tells you how to get started.)

Master the mix.

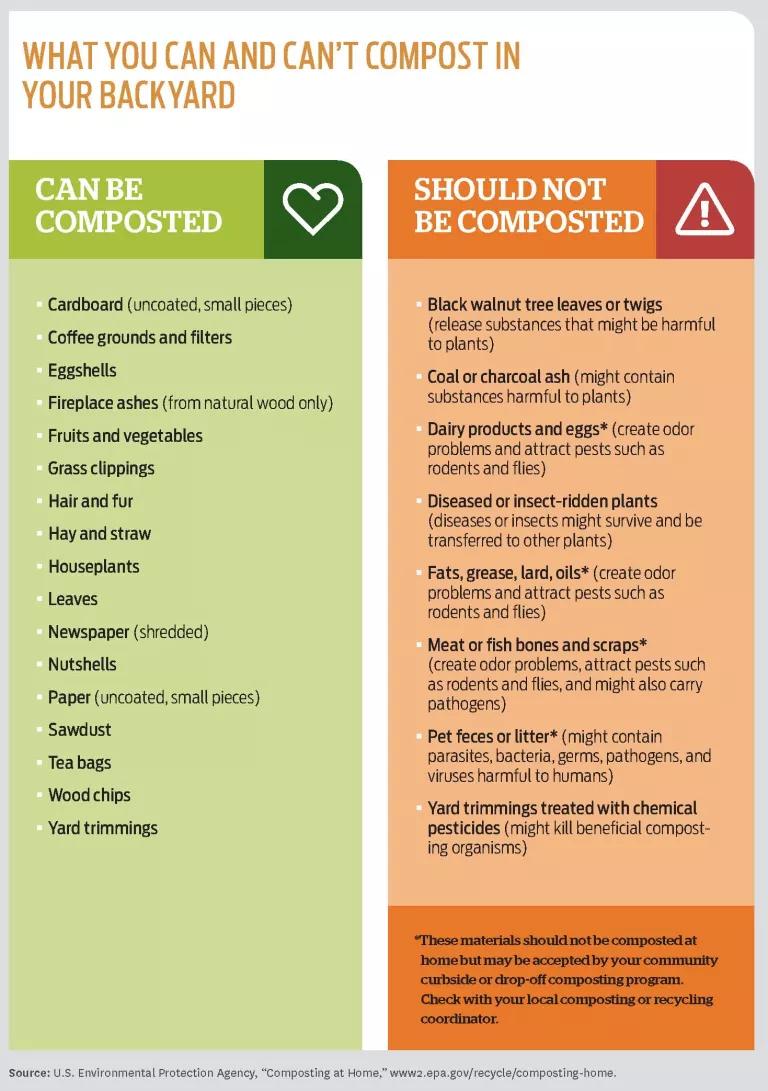

A pile of decomposing food might sound like the last thing you want in your backyard or under your sink. But if you do it right, you’ll hardly notice it’s there. “If you create the proper balance of materials, you’ll have aerobic conditions, and the microorganisms that thrive there break down scraps with little to no odor,” Hoover says. There’s an easy, color-coded formula to make sure this happens. Add two or three parts carbon-heavy “browns” for every one part nitrogen-centric “greens.“ The “browns” include shredded newspaper and other paper, dead leaves, and food-soiled paper napkins. (Just don’t use any coated, shiny paper, including milk cartons—they won’t break down sufficiently—or any treated or painted wood.) For “greens,“ toss in fruit and vegetable bits (scrape off any plastic stickers first), breads and grains, coffee grounds and filters, and grass clippings. To stash your scraps until you’re ready to haul them out to the yard, you may find it convenient to designate a pail under the sink or a bag in the freezer.

Be selective with your scraps.

There are a few food scraps that should still go out with the trash (or into your curbside “green“ bin, if you’re lucky enough to live in a city that accepts food scraps for centralized composting). Meat, bones, and dairy products don’t belong in the typical household compost pile. “You can’t guarantee that the internal heat generated by your compost will reach the temperatures required to kill pathogens that might be there,” Hoover says. Plus, they lure pests. “Meat scraps and bones will attract cats or skunks from a long distance, as will oils like olive oil,” says Bill Hlubik, a professor of agriculture and plant science at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey. When adding food scraps like bread products to your pile, it’s best to add in moderation and bury them in your heap to help reduce unwanted attention from pests. And before you get started on your composting, make sure you’ve followed our helpful tips to reduce the amount of food that gets wasted.

Let the rot set in.

Worried about care and maintenance? That’s easy, too. “In the summer, use a shovel or old garden fork to turn the pile once a week; in the winter, once every three or four weeks,” Hlubik says. “After each layer, I sprinkle on soil from the garden to add beneficial organisms, plus a little water to wash the organisms into the pile.” To tell whether your pile needs water, grab a handful; it should feel about as damp as a wrung-out sponge.

Use your pay dirt wisely.

Over a few weeks, those food scraps and shredded leaves will morph into soil-like dark matter. The compost is complete when it has a musty, earthy smell and you can’t recognize any of the items you dropped in. If you have a garden, sprinkle the compost around plants, mix it in with potting soil, or use it as a top dressing for your lawn.

Of course, if you live in a city, you may see composting as a really good way to get stuck with a giant tub of dirt. “Try to use your compost in houseplants—if it’s really broken down, you don’t even need any soil,” Hoover says. You can also share the bounty by offering friends, the whole office, or your children’s school a free donation. Another tactic is guerrilla composting: Dump some compost at the base of street trees.

Spread the word.

More and more local governments are recognizing that food waste is the bulk of what goes to their landfills and are starting to do something about it. About 3,560 community composting programs were documented by the EPA during its most recent count in 2013, and that number continues to grow. These larger-scale operations—often run in tandem with regular curbside garbage pickup—accept more types of food scraps than you can easily handle in the backyard. “You can sometimes add meat, dairy, and compostable plastics,” Hoover says. Check to see if your city has a composting program, and if not, be an advocate: Let your local leaders know you’d like to see it happen.

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

Food Waste 101

In Planning for Climate Change, Native Americans Draw on the Past

The Smart Seafood and Sustainable Fish Buying Guide