The Clean Energy Expert Bringing Black Voices to the Table

As NRDC’s California state lead for clean energy and equity, Alexis Cureton is working to ensure that communities of color help shape energy policy, both inside and outside of the energy sector.

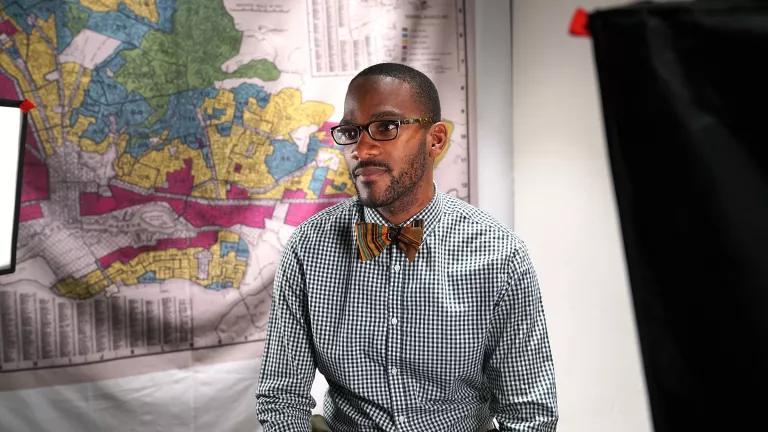

Alexis Cureton, California state lead of clean energy and equity at NRDC

The topic of energy rarely came up during Alexis Cureton’s childhood, split between Tulsa, Oklahoma, Duluth, Georgia, and Indianapolis. Nevertheless, Cureton can still recall his mother’s reminders to turn off the lights and not to overuse the dishwasher. Those pleas gave him an awareness of the scarcity, necessity, and costs of energy—heightened during those cold-weather stretches when his family’s finances did not allow them to pay the electric bill. Along the way, two questions formed in his head: “How is energy helping to create comfort and, in its absence, how am I uncomfortable?” Today, these questions shape Cureton’s lens at NRDC, where he advocates for California’s low-income communities of color to be at the energy decision-making table and for their access to clean energy.

A self-proclaimed nerd, avid reader, and documentary enthusiast growing up, Cureton found inspiration in the pages of inventor and engineer Nikola Tesla’s autobiography. Despite being born worlds away from Tesla—Black and in the home of Black Wall Street—he related to Tesla’s innovative ideas and that he did not fit in with the norm. “A lot of my interests weren’t really mainstream,” Cureton says.

Still, pursuing a career in energy was not on his radar, even with his interest in Tesla. As a teen, Cureton and his friends knew vaguely of solar panels and that they were installed in homes located in more affluent neighborhoods. But, he says, “we were not talking about creating energy businesses or lobbying for particular policies that improve the conditions of our community.”

For college, Cureton headed off to Clark Atlanta University to pursue an undergraduate degree in sociology. It was the same university where the man considered the “father of environmental justice,” Dr. Robert D. Bullard, had taught. Bullard left Clark Atlanta to teach at another institution the year before Cureton arrived; nevertheless, the professor’s writings would welcome him into the environmental sector.

At Indiana University’s School of Public and Environmental Affairs, where Cureton set out for an MPA in policy analysis, the door opened further for him when the school began to offer an energy major concentration. He followed his curiosity, entering the concentration as one of three African American students.

“It was a culture shock,” Cureton says, adding that many of his peers had been more deeply engaged in clean energy since their teen years. One classmate had been making mini solar panels in his garage for fun in high school. “I saw how late in the game I was exposed to this industry,” Cureton says. “I think about how many people feel that way.”

The few Black students in the concentration not only found themselves in the racial minority in the classroom—they also found no representation of themselves in the curriculum. “I learned that people whose books we were told to buy and to read over the summer were not Black. They were not writing from a Black perspective or about Black people,” Cureton says.

He worked to counter these feelings of isolation by focusing some of his independent graduate coursework on the federal government’s inadequate response to environmental justice concerns. He sought out professors like Dr. Edwardo Rhodes and Dr. Tony Reames. Friendships like these helped Cureton begin to read more widely on the topic, using stipends he received from summer fellowships to buy books that resonated with his experience as an African-American man in the United States. However, Cureton knew it would be important to build professional relationships outside of the program as well, and with that understanding, he forged a partnership with the American Association of Blacks in Energy to offer mentoring and internships to students of color in the program.

Dr. Bullard’s books solidified Cureton’s career journey. Through writings like The Wrong Complexion for Protection: How the Government Response to Disaster Endangers African American Communities, he learned that Black people had been fighting for the environment for a long time. Cureton felt as if the pages said, “Congratulations, you are part of that group.” And he no longer felt isolated in his career path.

Cureton went on to work as a researcher at organizations focused on creating equitable, community-focused clean energy transitions like Spark Northwest, the Greenlining Institute, and GRID Alternatives—groups that also help to create related job-training opportunities for underserved communities. He served as an electric vehicle fellow in the GRID Alternatives’ SolarCorps program, aiding efforts to provide access to clean mobility for low-income communities in California. (The group offers grants of up to $5,000 toward the purchase of new or used electric cars.)

Cureton explains that California’s affordable housing crisis has also impacted many residents’ transportation expenses since it’s pushed them into homes farther away from central business districts. As a result, he says, “many people are transportation burdened, meaning they are spending more than half of their income on gas.” While driving an electric vehicle slashes fuel costs, buying one is out of reach for many. And further compounding this access, he notes, low-income communities are too often left out of policy conversations that could help raise these affordability issues. “I always strive to make sure that what I advocate for comes directly from the community,” Cureton says.

The siting of transit infrastructure must also have local buy-in, he adds. For example, in Long Beach, California, which is among the nation’s most ozone-polluted metro areas, residential neighborhoods that are home to large Black and Latino populations surround Interstate 710. More than 40,000 diesel trucks traverse the corridor daily, as part of the city’s port infrastructure. Residents call it “asthma alley.” But no one chose to live amid this pollution, says Cureton. “Who made the decision to put the roads here? The community did not get to make the decision on road placement.”

In his role at NRDC, Cureton continues to bring community representatives to the table to broaden the conversation around clean energy solutions through the Energy Efficiency For All (EEFA) initiative. At the state level in California, EEFA advocates for sustainable clean energy investments in affordable housing. Some of these efforts include encouraging disadvantaged communities throughout the state to take advantage of the Low-Income Weatherization Program (LIWP), which helps renters afford energy efficiency upgrades like insulation and lighting that make their homes more comfortable while lowering their emissions and energy bills. Cureton has also been supporting the Repower LA coalition’s #EraseUtilityDebt campaign, which works to relieve the pressure on residents struggling to pay water and power bills in the face of increasing unemployment rates due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I love the position I am in. The work I am doing is tied directly to me,” Cureton says.

Even before the pandemic, one in three Americans were considered “energy insecure,” with low-income communities of color hit the hardest by inequitable energy policies. Now, the pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement have further amplified how much work needs to be done to create social policies that allow Black, Indigenous, and other communities of color to thrive, he points out. But he wishes that momentum did not take such tragedy.

“I don’t want to go through something that’s 10 times worse than this to finally get to where we need to go. I have lost too many people from COVID and ‘I can’t breathe,’ ” says Cureton. One of his best friends lost his father to the virus in August; another friend’s cousin, Dreasjon Reed, was shot and killed by the police in Indianapolis in May.

What keeps Cureton grounded in his work is his empathy—a trait he sees as a requirement for anyone entering this field. “I don’t think that you can work in climate, clean energy, and environment and not think about other people,” he says.

Equally fundamental to his work around utilities is his mission to boost energy literacy so that low-income communities of color can become their own advocates. “How do I communicate to my people this complex concept of energy and how it impacts them?” Cureton asks. He cites Malcolm X, who could articulate the lived experiences of his people—and who served as an intermediary between those oppressing and those fighting to no longer be oppressed—as an inspiration for his work in both the policy space and on the ground.

“Energy has played a huge role in the ways that Black people live and experience life in this country,” Cureton says. It is his mission to light the path forward.

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

A Commitment to Equity—in the City, the Classroom, and Even the Jungle

When a Study Singled Out Memphis’s Unfairly High Power Bills, Grassroots Groups Took Action

This Is How We Stand Up to Trump