California Lessons for Federal & State Workplace Heat Rules

California’s workplace heat standard is a good starting point for other state and federal officials to follow, but improvements are needed to fully protect workers from high temperatures.

A car wash worker in southern California.

California’s recent record-breaking heat was particularly brutal for the workers who walk for miles, lift heavy loads, sweat in oppressively hot uniforms, and endure bosses who care more for their profits than their people. School cafeteria workers, farmworkers, delivery drivers, and others across the state experienced unhealthy temperatures that left them faint, in the hospital, or worse. These are just a few examples of the kind of preventable harm workers face every year from heat. But they’re particularly infuriating coming from California, which is one of only five states in the country with workplace heat stress protections. What’s going wrong?

California has one of the oldest and most robust occupational heat standards in the country, making it a ready model for other worker protection agencies to follow in the absence of a federal heat standard. Until now, however, there has been little research on compliance with these rules or how that compliance affects workers. A new report I co-authored helps fill that research gap and provides valuable insights as advocates continue to call for a strong, enforceable federal heat stress standard.

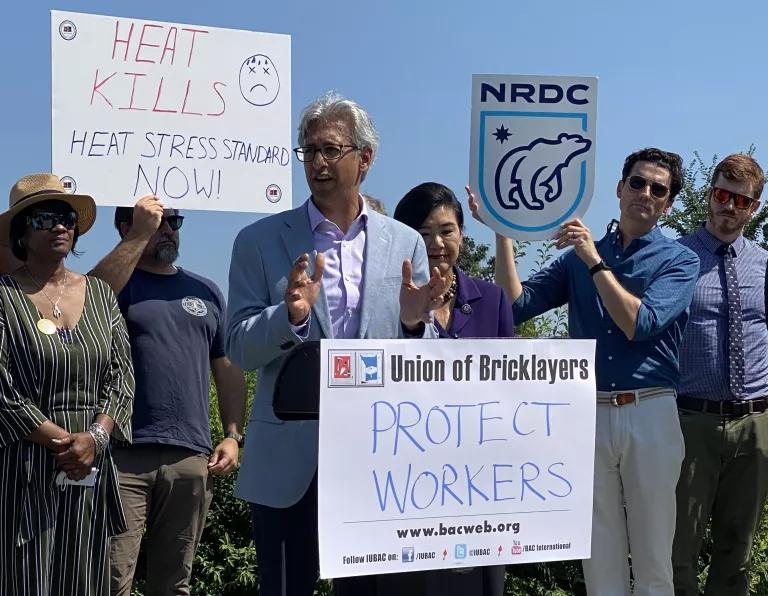

NRDC President Manish Bapna speaking at a heat stress event with Rep. Judy Chu, Sen. Alex Padilla, and members and leaders from the Bricklayers and the United Food and Commercial Workers unions.

The Golden State’s heat standard, which only covers outdoor workers, requires employers to provide heat training, free drinking water, and shade to employees. Employers also must develop procedures for particularly hot days and for heat illness emergencies, and to closely observe new employees as they get used to working in the heat. The standard was first adopted on an emergency basis in 2005 and has been made permanent and amended twice more since then.

What we learned about the California experience

My former colleague Teni Adewumi-Gunn and I used a novel analysis of nearly 500 fatal or catastrophic heat-related incidents from 2005 to 2019 and more than 16,000 heat citations from January 2005 to May 2021 to assess how implementation of the California rule is going. Our key findings are below.

- Heat-related illnesses and injuries affect workers in agriculture more than workers in any other industry. Farmworkers accounted for 36 percent of 70 overall heat deaths, and the Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing, and Hunting industry made up nearly 50 percent of serious and willful violations of California’s heat standard.

- However, heat-related illnesses and injuries can occur in almost any workplace. We identified heat-related cases in 463 different industries outside agriculture and construction, including janitorial services, home health care, museums, and newspaper publishers.

- Close to 40 percent of heat violations found during Cal/OSHA’s unprogrammed inspections stemmed from complaints made by workers, unions, employee representatives, and other interested parties. This finding illustrates the vital role of complaints in workplace health and safety—and how important it is for agencies to protect vulnerable workers from employer retaliation.

- 55 percent of overall citations were issued to employers who failed to adequately train employees or keep satisfactory training records. Training is a relatively low-cost way to ensure that workers and their supervisors have the tools they need to identify and respond to heat-related illnesses, which can become medical emergencies in a matter of minutes.

- Hundreds of businesses repeatedly violated the California heat standard but avoided the higher fines typically associated with a “repeat violation.” Thirteen of the 15 establishments with the most heat-related citations received no more than one citation for a repeat violation. The case of UPS was particularly egregious, with 41 citations for violating the heat standard but only one citation for a repeat violation.

- Cal/OSHA routinely gave employers steep discounts on penalties for heat-related citations, sometimes down to $0.

Farmworkers packaging lettuce near Salinas, California.

Our report also includes first-hand narratives from workers, union members, and worker advocacy organizations. We heard that employee experiences with the California heat standard greatly differ, with vulnerable worker populations such as farmworkers bearing the brunt of employer inaction. Day laborers Mario* and Pedro* spoke about how employers don’t provide shade or sufficient water, leaving workers to drink out of dubious garden hoses or even to go without water. Joaquin*, a 15-year veteran of the car wash industry in Los Angeles, gets marks on his skin when the plastic logo on his required uniform heats up in the sun. Contrast these experiences with union workers from the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, whose employers provide air-conditioned trailers, cool towels, and plenty of clean drinking water.

What we recommend for California and beyond

Although California’s heat standard is a good starting point for other states and OSHA to consider, many improvements are needed. These include:

- Developing standards to protect indoor workers.

- Ensuring standards have sufficient detail on how employers should provide potentially life-saving elements such as water, rest, shade, training, and acclimatization procedures.

- Strengthening enforcement by hiring sufficient staff (including bilingual inspectors) and revising policies for issuing repeat citations, setting maximum penalties, and reducing total citations.

- Better protecting workers from employer retaliation for reporting unsafe conditions.

Heat illnesses and deaths are preventable if employers and workers consistently apply commonsense measures. As our new report shows, however, far too many workers in California fall through the cracks created by a lack of indoor standards, vague standard language, insufficient enforcement, and a penalty system that makes it more attractive for some employers to break the rules than to follow them.

California has been a leader in heat stress protections for workers. State regulators should continue that leadership by adopting the recommendations above—and other states and the federal government should develop and enforce strong new standards without delay.

* Workers’ names have been changed to protect their confidentiality.