Part of NRDC's Year-End Series Reviewing 2015 Energy Developments

The Paris climate talks gave strong impetus to the world's determination to curtail climate pollution through policies that create jobs and economic growth while simultaneously cutting emissions. While they may be a lower profile solution, improved building codes are a cornerstone of a successful climate policy.

One reason for the paucity of discussion of codes is that climate policy is made on a national level, while in the United States and many other countries, energy codes are adopted and enforced primarily at the state or even local level.

Nevertheless, new energy codes have the potential to save 160 MMTCE (million metric tons of carbon equivalent) of climate pollution in America by 2030--some 3 percent of emissions of the entire nation-- merely by adopting model codes that already exist. Adopting the 2015 version of the International Energy Conservation Code (IECC) would result in emissions savings with an economic benefit of a quarter of a trillion dollars over the next 15 years.

These savings compound over time: by 2050 the savings will be about double the savings in 2030, just because the codes apply to more and more buildings that have been constructed since 2015.

Savings will also get much larger for two reasons explored next:

Savings from flexibility to builders

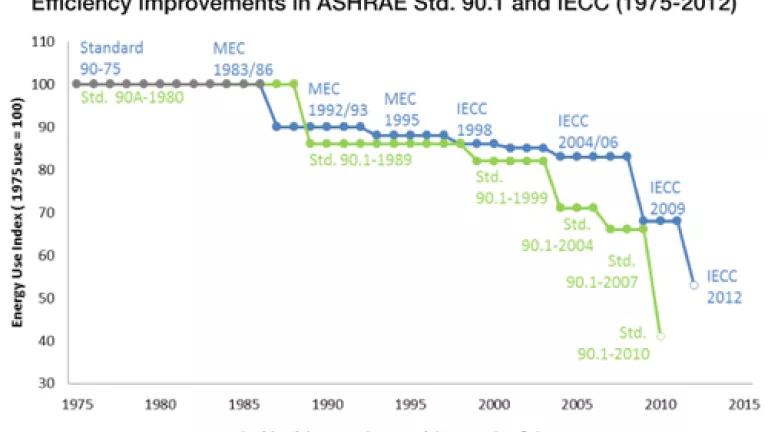

NRDC actively works with coalitions of businesses and other nonprofits to raise the bar on energy codes. Figure 1 shows the progress of codes.

Figure 1. progress of model codes in the United States

The IECC code applies most commonly to residential buildings, while the ASHRAE standard is exclusively for commercial buildings. Both standards are voluntary models, but all U.S. states are required by law to adopt or consider them, and some foreign jurisdictions adopt them or modify and adopt them as well.

Figure 1 demonstrates the accelerating progress we have made since the 2004-6 codes, which were hardly changed compared to 1975. From 2006 until 2012, coalitions in support of stronger codes succeeded in getting a reduction in energy use of some 30 percent.

During the debate over the code for 2015, NRDC believed that there was still potential for more savings. By offering home builders something they really wanted--flexibility and the reduction of administrative burden--in return for increased savings, NRDC successfully helped to create an alternative path for homebuilders to comply with the code. The 2015 IECC contains a new tradeoff method that allows a home to meet an Energy Rating Index (ERI), the most prevalent of which is the HERS index. Using the ERI path to comply with the 2015 code requires savings of at least 45 percent compared to 2006, but allows for increased flexibility with how the savings are achieved.

The ERI is like a miles-per-gallon rating for homes, in which a score of 100 means the home meets the 2006 IECC code and a score of zero means that home has no net energy consumption. Thus a score of 60 means an energy savings of 40 percent.

Inclusion of the ERI is valuable to consumers: it tells the buyer how efficient the home is and how much money they should expect to spend on utility costs. The HERS score makes efficiency visible by allowing comparisons between homes. As about one-third of all new homes sold in 2014 were rated with a HERS score, there is competition between builders for a lower score. Thus, even though the tightest codes result in the average home having a HERS score of about 69, and even though most jurisdictions enforce the weaker 2009 code, the average HERS score last year was 63, showing that the existence of HERS scores on a wide basis is causing competition among builders over how much better than code their efficiency is.

This year, the 2015 code has been adopted in several states, including Vermont, Illinois, and Maryland, and is in the process of adoption in several others.

Even in states that did not cleanly adopt the model 2015 IECC building code, we still saw some progress. For example, in Texas, the largest new homes market in the country, the legislature passed a law that adopts the same prescriptive check-list of required insulation levels, etc., as in the 2015 IECC as well as the optional ERI method. While the Texas code contains ERI scores that are higher (therefore, weaker) than the 2015 model code, either method of compliance is a substantial improvement over the 2009 code.

Savings from continual improvement

Most studies of efficiency potential answer the question of how much we would save if we used technologies current at the time of the analysis, but do not assume any improvement in those technologies. But in areas where we have tried consistently to improve efficiency through up-to-date policies, we have seen rates of improvement in energy consumption of 6 percent per year or more. The study whose results I cited above distinguishes itself by modeling an improvement of 5 percent for every code cycle.

Code cycles occur every three years, so this is a very modest assumption. As noted above, we have been able to achieve savings of about 15 percent every code cycle since 2006. An improvement rate of 6 percent per year--which we have achieved in the California energy code since 1975--would yield a 20 percent improvement per triennial cycle. This would lead to a much larger savings projection, especially for 2050.

Other areas where we have been able to achieve continual improvement rates of 6 percent annually are noted in my book, "Invisible Energy: Strategies to Rescue the Economy and Save the Planet."

What's next?

In advance of the next code cycle beginning in 2018, NRDC is working with a broad variety of stakeholders both to tighten efficiency requirements by about 5 to 10 percent and to set minimum requirements for savings from efficiency alone before accounting for solar generation. Currently, it is unclear whether the version of the ERI score used in the IECC counts energy savings from solar.

NRDC supports a middle-ground proposal that will allow some solar tradeoff but also guarantee a minimum level of efficiency. While investing in energy efficiency is ultimately cheaper to the consumer, there are attractive financing options and tax credits that help reduce the upfront costs to the builder of solar generation equipment and thus create a non-level playing field. NRDC fully supports efforts to increase solar power, but solar must be coupled with appropriate levels of efficiency to be most effective. This type of limited tradeoff for solar power is already being used in Vermont and Massachusetts.

Energy Codes in California

So far we have talked about codes in most states, which rely on national models. But California maintains its own code, which is usually more advanced than those of other states. This year the California Energy Commission adopted code upgrades that will save some 25 percent of energy use compared to the previous code, following a 2016 update that itself saves some 25 percent. We are working with the Commission and with stakeholders to assure that the 2019 California code is consistent with the state's goal of zero-net-energy homes by 2020 (meaning the home's total annual energy use is roughly equal to the amount of renewable energy created onsite).

We are also working collaboratively with builders to try to harmonize California's HERS system with the national system. Currently, the California system is minimally used: builders and retrofitters find it too bureaucratic. Its outputs do not agree with those of the national system, so that a HERS 80 home in California may use less energy than a HERS 65 in Nevada. While some advanced features of the California system should be retained, and perhaps extended to the national system, in other areas the two systems disagree without any good reason. This is a barrier to using HERS ratings for consumer transparency in California--a barrier we hope to eliminate in 2016.

Energy codes are a powerful tool for cutting emissions and lifting the economy. NRDC plans to begin the next three-year processes of continually improving energy codes at the national and state levels and anticipates strong success in 2016 and beyond. We encourage states and cities to adopt the most current codes to maximize emissions savings and job creation.