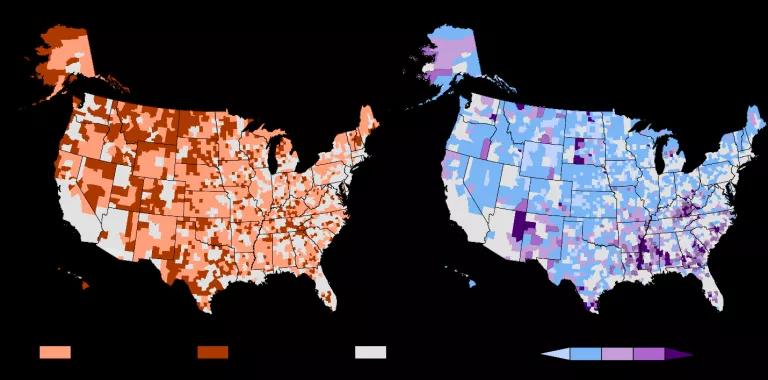

The 2018 midterm election was a resounding win for environment, with pro-environment candidates winning governorships, Congressional seats, and state legislative races across the country. But the striking contrast between the results in the House and Senate also revealed widening of the so-called rural-urban divide.

In many rural communities, there’s a feeling of being left behind. Forgotten. Small communities are getting smaller. Stores and schools are closing. For example, in my mom’s hometown Rising City, Nebraska (population 356), the beautiful old high school building was demolished about a year ago. The building was no longer in use because the school district merged with a neighboring community. But the wrecking ball provided a visceral metaphor for what rural communities are experiencing more broadly.

The recent National Climate Assessment (NCA) affirmed that rural communities are indeed experiencing both declining populations and increasing poverty. Specifically, a historic number of rural counties are losing young adults to metro areas, as well as facing slower employment growth and higher poverty rates than their urban counterparts.

Without a doubt, the way of life in these communities has changed. At one time, generations of families lived on the same land. One farm could support large, extended families. Now, we’re seeing people leave farms for urban areas, partly because land can’t support same number of people. With technological innovation, specialization, and mechanization pushing production to heights that were at one time unimaginable, labor is no longer the limiting factor in agricultural production.

Not all of this transformation is bad. I’m one of the urbanites-formerly-known-as-a-farm-girl, having grown up as the fifth generation on my family’s farm in Nebraska. And I undoubtedly benefited from this mass exodus in many ways. Growing up, I felt I had many options open to me; I never felt I “had” to stay on the farm, because my dad didn’t “need” me there to work. I was the first in my family to go to graduate school. I have a beautiful life in California. But could the family farm support my parents and my young and growing family if that’s what my husband and I wanted? Maybe, but I don’t know for sure.

Climate change is expected to exacerbate the challenges rural communities are confronting. Scientists expect climate change to increase the number of both droughts and extreme precipitation events. Both of these impacts, in turn, reduce agricultural productivity and further aggravate climate change—droughts reduce vegetation growth, which limits carbon sequestration; extreme precipitation worsens erosion, which causes soil carbon stocks to be lost. As the NCA points out, rural communities bear the brunt of these changes:

“[R]ural residents are also highly vulnerable to climate change effects due to their economic dependence on their natural resource base, which is subject to multiple climate stressors.”

But there are farmers out there who are trying different models of agriculture to help bring more people—young people—back to the farm, combat climate change, and support rural revitalization. Instead of focusing on specialization, these farmers are reintroducing diversity to their production model and producing a wide array of crops and livestock. Their focus is on regenerating land. That means using their complex crop rotations to break weed, pest, and disease cycles. It means using practices like cover crops and no-till to protect and restore the soil. It means intensively managing their livestock to provide optimal nutrient application.

This regenerative model of farming is good for rural economies, because it can support a larger labor force and it can provide millions of dollars’ worth of ecological services. And it can do so while remaining profitable, because it reduces reliance on expensive chemical inputs. Research out of Iowa State University has demonstrated that moving from a 2-year to a 3- or 4-year crop rotation can cut energy, synthetic nitrogen, and herbicide costs. Labor costs increase in the longer rotations (hello, rural jobs), but profitability remains essentially unchanged.

Regenerative agriculture also supports the burgeoning sustainable agriculture economy, including soil scientists and cover crop seed dealers. And it helps farmers become more resilient in the face of extreme weather caused by climate change.

Regenerative agriculture could be what we need to finally bridge the infamous rural-urban divide, revitalize rural communities, confront climate change, and restore some of the “greatness” that some rural Americans feel they’ve lost.